A discussion of the ethics of gem treatment disclosure, a comparison of gem treatments, and the crisis these could bring to the industry if mishandled.

…Moreover, I have in my library certain books by authors now living, whom I would under no circumstances name… containing, for example, information on how to make a sardonychus [sardonyx] from a sarda [carnelian, in part sard]: in other words, how to transform one stone into another. To tell the truth, there is no fraud or deceit in the world that yields greater gain and profit than that of counterfeiting gems. Pliny [23–79 AD], Historie of the World

Gem Treatment Disclosure • Trust

Since early times, gemstones have been objects of desire. Indeed, the historical record is littered with examples of wars fought, cities sacked and duels dueled, all to possess these precious objects. Naturally enough, the scarcity and high value of gems has also led to fraud.

It is clear from the above that the "improvement" of lesser stones was not considered a path to heaven, nor did it earn merit for the next lifetime. And yet, what Pliny considered "fraud" is often referred by some today as: "finishing the job that nature started."

I do not support such broad-brush rationalization. With a definition like this, death simply finishes the job that birth started. I believe what happens in between matters, too.

Value

Everyone is taught that gemstones are valuable for three primary reasons – beauty, rarity and durability. Let's consider treatments in light of these factors.

The purpose of a treatment is to increase value, usually via improvement in appearance. So what is the relative value of a treated stone as compared to its natural counterpart? If we compare two stones of equal beauty and durability, the only remaining factor is rarity.

Heat

How does heat treatment affect rarity? The answer is dramatically – a radical increase in the number of beautiful stones in the marketplace

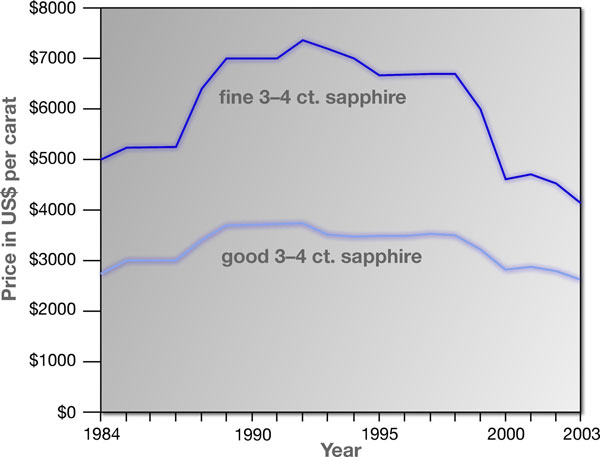

The production of gem-quality stones from any mine is only a small fraction of total production. Most specimens are too impure to be cut into gems. Consider Sri Lankan sapphire. Far more geuda (impure corundum) than gem-quality sapphire is produced, perhaps 100 times as much. Beginning in the mid-1970s, the widespread adoption of effective treatments for Sri Lankan geuda dramatically increased the availability of fine blue sapphire. This resulted in a stagnation of sapphire prices that has continued for decades. As more and more gems undergo more drastic treatments, we have to ask if this is the future of the gemstone business.

Graph tracking the price of 3–4 ct. sapphires over the past 20 years. The Good category corresponds to levels 5 and 6 in the GemGuide, while Fine represents levels 7 and 8. Price data courtesy of Stuart Robertson of the GemGuide; graphic courtesy of Richard W. Hughes.

Graph tracking the price of 3–4 ct. sapphires over the past 20 years. The Good category corresponds to levels 5 and 6 in the GemGuide, while Fine represents levels 7 and 8. Price data courtesy of Stuart Robertson of the GemGuide; graphic courtesy of Richard W. Hughes.

And flux

In the late-1980s, large quantities of heavily fractured purplish rubies were discovered at Mong Hsu, Burma. Enter the oven, exit fine reds, the likes of which had never been previously seen in over two millennia of ruby production. What's up?

Heating plus flux. The heat banished the blue in the stones, turning purple to red. But what about those cracks? They were also taken care of. Addition of fluxes during the heating process literally dissolved the walls of the fractures and redeposited synthetic corundum, healing the problem away. Cracks no more. How many customers that purchased these stones were told that they contain microscopic amounts of synthetic corundum as a fracture filler?

None. No one has been told. Instead the treatment has been obscured by words about glass "residues from the heating process" on laboratory reports. So obtuse is this language that even most dealers are unaware of exactly what has occurred with these stones.

And beryllium

In 2001, again without disclosure, stones treated by a new process entered the market. The color of these stones resulted from diffusing beryllium into them from the outside, just like dyeing cloth. This process allowed one to manufacture yellow, padparadscha, and orange sapphire from low-value starting material. Later, it was shown that beryllium diffusion could also lighten overly dark blue sapphire. Suddenly the search for the Holy Grail was over. This "manufacturing" process had the potential to dramatically rewrite the book on corundum rarity, allowing treaters to almost dye a stone at will.

What is the impact on rarity? Beryllium diffusion can increase the availability of yellow sapphire by a factor of over 1000, and of padparadscha, because of its natural rarity, by even larger factors. The sky is the limit for blue sapphire. What does this say about value?

Disclosure?

Virtually all gem trade associations have treatment disclosure policies. In reading them it is unclear if they are intended to truly inform the buyer or provide legal protections for the seller. It is certainly the rare sales person that can explain what has been done to a stone and put that information in a value-oriented context. In today's market, value is determined far more by traders than an informed purchasing public.

Consumers are rarely told that this sapphire has been heated above the melting point of steel and thus is a hundred times less rare that a natural sapphire of similar appearance. Nor do many explain to the retail customer that a yellow sapphire was manufactured from nearly colorless low-value corundum via beryllium diffusion.

What might be the value of a heat-treated sapphire if a consumer had a full understanding of these realities? Would he or she be willing to pay a hundredth the price of the natural sapphire, a tenth, a third, or more? We simply don't know. What about stones manufactured by beryllium diffusion?

How about synthetic sapphire? Might retail buyers prefer a large beautiful synthetic sapphire, once they truly understood how close to synthetic so many stones are today?

What would happen to values if the arcane knowledge of treatments became public? To date, few customers have been offered an honest description of treatments at the time of purchase. Who knows what might happen if they were?

Rebottling the genie

As we move into the future, gem enhancements will not become any less effective, nor will detection become easier. Increasingly sophisticated treatments have driven the cost of a thorough lab report on a corundum gem to levels that are prohibitive for most gems under a few carats. From heated geuda sapphires, through titanium diffusion, glass-cavity filling, flux-fracture healing and beryllium diffusion, the past 30 years have seen one treatment after another foisted upon an unwary world without regard for proper disclosure. We used to believe in magic. We believed everyone could get rich by making silk purses out of sows' ears. But we failed to see the future.

The future has arrived. Senior industry analyst Russell Shor, in the March 9, 2007 GIA Insider wrote:

Thailand's gemstone manufacturing industry is in a crisis, according to its leaders, who report that many gem cutters in Chanthaburi have closed or suspended operations.

The two major trade associations have petitioned the government for funds to promote their gems in world markets and to establish a reasonable, government-sanctioned standard for disclosure of treatments.…

Exhibitors at the recent Thailand Gems and Jewellery Fair in Bangkok were offering sapphires in a variety of colors for as little as $5 per carat (less if you wanted to bargain and/or buy in quantity) without a lot of takers. Some exhibitors labeled diffusion-treated materials clearly, others did not. Buyers were unsure of what they were getting and, with only sporadic disclosure, sapphire prices for all colors have fallen to the level of greatest doubt…

Russell Shor, "Analysis: Thai Dealers Seek Government Help to Avert Crisis"

We rubbed the magic lamp, the genie granted our wishes. And suddenly we've decided we don't believe in magic after all.

Trust is…

And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make. The Beatles, The End

In recent years, a portion of the gem community has embraced the Fair Trade Movement, which seeks to ensure that mining and cutting of gemstones is carried out under safe, environmentally acceptable conditions, with fair compensation for all involved.

The concept is simple: fair play. It seeks to ensure that no single member of the supply chain can prey upon another. One of the basic tenets of this idea is full disclosure of treatments. Again, the concept is simple: buyers should understand exactly what has been done to a gem before making a purchase decision.

Today, the gulf between disclosure and understanding is not unlike that between birth and death. It is a vast chasm.

What lies between? It is not trivial. Disclosure is not enough. We must explain, we must teach, we must educate.

In the end, it's all about trust. We must trust customers enough to realize that their education and understanding are crucial to everyone's success.

Trust. In the end, it's no different than love.

About the authors

Dr. John Emmett is one of the world's foremost authorities on the heat treatment, physics, and chemistry of corundum. He is a former associate director of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and a co-founder of Crystal Chemistry, which is involved with heat treatment of gemstones.

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard's Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology.

Notes

Penned in March, 2007. Appeared in Jewellery News Asia, May 2007.