Since the late 1960's, East Africa has been home to some of planet earth's greatest gem discoveries. And yet, little has been written about certain of these finds. In the autumn of 2007, the authors set out to fill in the gaps, specifically regarding Tanzania's Mahenge, Songea and Tunduru regions.

Against my will—in the course of my travels—the belief that everything worth knowing was known at Cambridge gradually wore off. In this respect, my travels were very useful to me. Bertrand Russell

Gem Hunting in Mahenge & Tunduru Tanzania

In today's world, every square meter appears GPS'd and gentrified. And yet, to find adventure all one needs to do is step off the map. Want something new? Move a few meters from the road. Want the experience of a lifetime? Spend a few weeks off the chart. In doing so, you seem to stride back but—in doing so—might actually be taking giant steps in an entirely different direction.

October 6, 2007: Arusha—Entering the Underworld

Arusha is East Africa's safari capital. With the planet's highest Land Rover quotient, it might not seem the proper place to start a journey to the past. Yet one must start somewhere. We did not come to count horns nor stuffed heads. Our quarry roamed not the Ngorongoro Crater nor the Rift Valley. It did not travel the Serengeti on hoof nor padded foot. It wore not spectacular plume, nor subtle camouflage.

The game we sought was none of the above. Ours oozed from underground—iridescent treasure from East Africa's caldron of subterranean creation—the Mozambique Orogenic Belt. We were hunters—but of a different sort—stalkers of the underworld. In plumbing those depths, we hit treasure over and over again. This is the story of our journey.

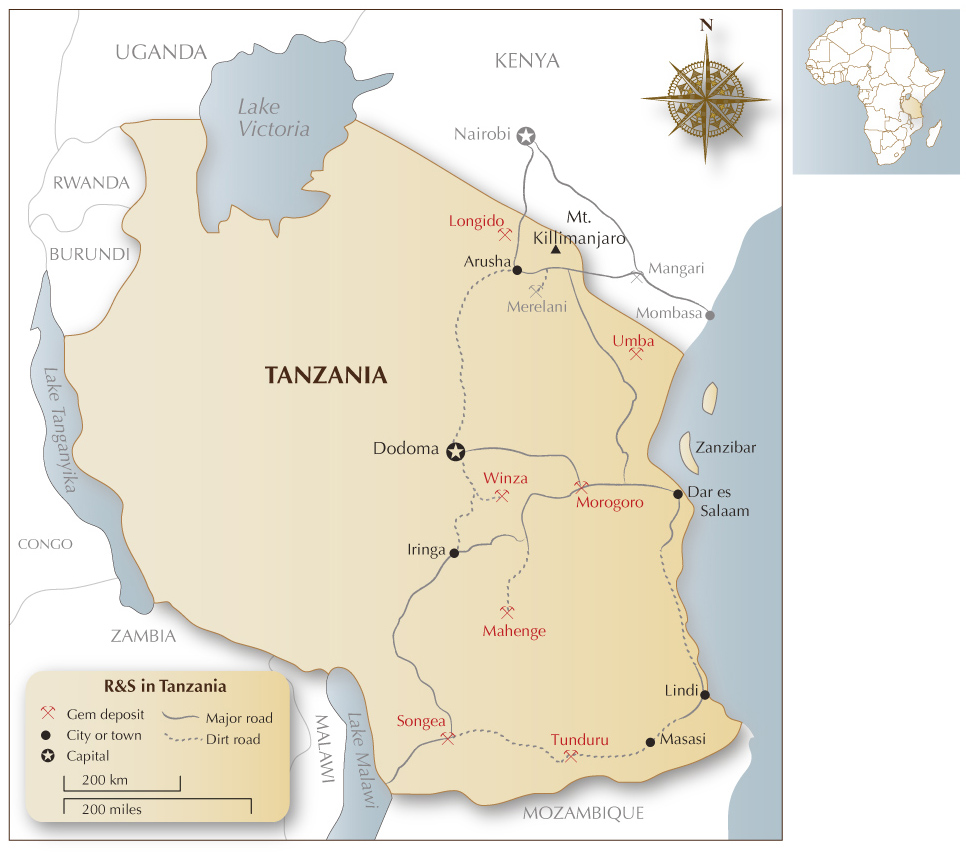

Map of Tanzania and southern Kenya, show the major gem localities. Map © R.W. Hughes

The initial targets were the corundum deposits of Songea and Tunduru, in Tanzania's deep south. Not simply off the the beaten path, but down into some of the darkest regions of the Dark Continent.

Our guidebook was an 800-page volume that devoted a few bare paragraphs to the region and yet still managed to capture the essence:

The 273 km Songea to Tunduru road, mostly through thick, tsetse-fly infested miombo woodland, is probably the worst in the country and is covered by buses only in the dry season.… The reward for your efforts is a night at the rough gemstone mining town of Tunduru, which should give you the necessary resolve to move on the following day.

– Jens Finke (2006) The Rough Guide to Tanzania

Our kind of place. Like a hungry lion, the Insane Gem Posse licked its lips in anticipation.

In any venture, timing is important, and in this respect we were most fortunate. Just prior to our arrival in Arusha, giant red spinel crystals were found in Mahenge, setting off a red rush that has continued to rain good fortune on those prescient enough to understand how vastly undervalued red spinel had been. Thus Mahenge was added to our target list.

Arusha's gem market was buzzing with the news: four giant crystals of 52, 30, 20 and 9 kg had been found in August, unleashing an unprecedented flood of fine red spinel into the world market. We did not see these massive crystals with our own eyes; for ease of transport and cutting, they were rapidly broken into smaller pieces. But we did taste the fruit. In Arusha, we were shown a remarkable tray of reds, each piece clean, matched in color and above ten carats. It was enough to make a committed commie go completely Donald Trump.

Girls from Ipanko

Oo la la. Spectacular faceted red spinels from the 2007 Mahenge strike at Ipanko, along with their uncut brethren. At the 2008 Basel Fair, a stunning set with more than 15 stones from 15–40 carats sold for a record price. Two of the faceted stones from that set are shown above. Photo: Vincent Pardieu/Gübelin Gem Lab; stones courtesy of Paul Wild

October 7: Arusha to Morogoro

Following a visit to the market in Arusha to stock up on supplies for the journey ahead, we hit the road for the eight-hour drive to Morogoro. The Morogoro region became famous in 1986, following the discovery of ruby and spinel near the village of Matombo, east of Morogoro town. Sadly, while VP found miners at Matombo in 2005, by October 2007, we were told all mining had ceased. [in 2009, VP went back to Matombo and found some miners still working the deposit]

A bit of candy in the office of Spiro, a Morogoro-based Greek dealer. Rough spinel from the Summer 2007 find at Mahenge. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

October 8: Morogoro

In East Africa, a visit to a mining area typically involves first visiting the local authorities to obtain permission to visit the sites. Thus on October 8th, 2007 we visited the Morogoro mining officer to get his support to enter mining areas in Morogoro province. Following that, we dropped by the workshop of Spiro, a Greek gem dealer, who updated us on Tanzania's past and current gem production. In addition to rough spinel from Mahenge, he showed us a number of other gems.

Philippe Brunot holding a spinel crystal from Mahenge. Photo: Guillaume Soubiraa

Gone, Gone, Gongoni

That afternoon we took the road to Gongoni, near Kilosa to visit a moonstone mine worked by AAK Brothers Co., Ltd. Moonstone was reported to have been discovered there in 2000 and the mine produced fine material from September 2003 to October 2006. We say moonstone, but some gemologists have suggested that the word peristerite is more appropriate, since this adularescent feldspar material is not orthoclase with thin layers of albite (like the moonstones from Sri Lanka or Burma), but albite with thin layers of orthoclase. Get it?

Such nomenclature issues are weighty matters, particularly for those who never had the opportunity to try and sell someone a stone and get the question back: "Huh? What the hell's that?"

For what it's worth, here are our definitions of both:

Moonstone: A feldspar gem that shows the lovely billowy light phenomena known as adularescence. This frequently engenders romantic thoughts that lead to booty action when the gem is offered to either girlfriend, fiancé or bride.

Peristerite: A feldspar abstraction that leads to complete cessation of booty action when offered to either girlfriend, fiancé or bride. Synonym: buzzkill.

Moonstone or peristerite? Only your microprobe knows for sure. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Needless to say, this subject was not a major topic as we approached the mine. Our focus lay on grabbing as much moonstone as possible and bringing it on home for some serious mating games. Sadly, 'twas not to be, for one simple reason. Gongoni was gone. The mines were lifeless, with only a couple bored guards with homemade weapons watching the rust grow on abandoned equipment next to a large-and-oh-so-empty hole.

The abandoned Gongoni moonstone mine, near Kilosa, outside of Morogoro. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

It seems the miners had moved on to Mahenge for spinel. But we did not return to Morogoro completely empty handed, as a guard at the moonstone mine said some 200 people were down the hill digging corundum. A short walk brought us to this deposit at Mbuyini.

Production from this alluvial corundum mine was sold by the owner to an Indian dealer in Dar Es Salaam. That dealer would heat the stones and dyed them, probably to make beads for the Jaipur market. All the miners working in the area had to sell the stone to the owner of the mine for 12,000 shilling/kg (about US$10/kg).

.jpg)

Corundum crystals from a deposit near Mbuyini, outside of Morogoro. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

Miners were mostly farmers. Peter Chelwa from Mbuyini village told us that "getting a little bit of cash mining here was better than staying at home doing nothing." He said that in this area teams of 3–4 miners would dig 3–5 days to reach the gem bearing gravels, which would then be washed to obtain the corundum. At times there were many stones, other times none. But the average miner could expect to make about $2 per day. While it might seem a pittance to readers from abroad, the miners told us it was good money for them, as their farms were poor and this little cash was welcome during the dry season when there was not much to do.

October 9: Morogoro to Mahenge

We left Morogoro early with Mr. Bakari Shemsanga, a mining technician from the Morogoro mining office, for the long but scenic drive to Mahenge. The road passed through the Mikumi and Udzungwa National Parks, enabling us to enjoy the sight of elephants, antelopes, buffaloes, giraffes and monkeys.

An elephant in the Mikumi National Park, along the road to Mahenge. Photo: Michael Rogers

Along the way we met up with local gem dealers traveling on motorbikes from Mahenge to Morogoro or Dar Es Salaam. At Mahenge, motorbikes and cell phones are key tools of the local gem trade because the poor security situation has prevented development of a local gem market.

We arrived in Mahenge, which was in the grip of both fear and spinel fever. A company had arrived recently in the area and with rigged documents, forced local miners to move out of the property where the large crystals had been found. This did not sit nicely and, just days before our arrival, said miners had gone on a rampage, burning cars and rioting in Mahenge town.

That evening, we met with one man who had been involved with one of the larger crystals and he described prices which were quite simply off the scale. We were incredulous, for finer goods were changing hands at more than US$10,000 per carat, this at a time when none of us had ever heard of spinel selling for even more than a third of that. The next day our plan was to visit those very mines and see with our own eyes what the fuss was about.

.jpg)

Mahenge, site of the spectacular spinel find in the summer of 2007. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

October 10: The mines of Mahenge

We awoke early, driving south towards the Lukande ruby region, a place close to the famous Selous Game Reserve. Along the way we passed near Kitonga, which produced cabochon-quality rubies from 1988 to 1993. Small scale mining involving possibly 3–5 miners was reported to be still occurring in the area. We then continued past Mbangayao mountain, which is a game reserve. It was also reported to have produced cabochon-quality rubies in the 1990's.

Rubies from Lukande, near Mahenge. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Further along was Mbarabanga, where between 30 to 50 miners worked a deposit of ruby and color-change spinel. Finally we reached Lukande, which was active from 1986–1992 when Thais operated the "Simba" mine. Tanzanian miners told us that it had closed due to riots. It seems a Tanzanian claim-jumper trespassed onto the property to steal gems. The Thais killed the thief, but their camp was subsequently attacked by a mob of angry Tanzanians; three people were reportedly killed. Following the riots, the Thai miners left the area to start working in Songea, where sapphire and ruby had just been discovered.

Mr. Esperitus, displaying his ruby find at Lukande, near Mahenge. He was responsible for first discovering the spinel mines at Ipanko. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

According to miners with whom we spoke, a local hunter named Mr. Gutapak found a big red stone in 1989. He brought this to a villager, Mr. Mash, who proceeded to take out a mining claim on the whole area and started mining, with the hunter becoming a security guard. From 1990 to 1994, a Thai partner named Khun Tom was taken on, and the mine became known as the "Tom mine." Mining stopped in 1994 as the miners moved to the new Tunduru deposit.

At the time of our visit, small scale mining was present in Lukande, Mayote and Chipa, with about twenty miners at each locality. We observed mining at Lukande at an alluvial placer, along with a primary deposit on a hillside, where rubies were found in marble associated with mica. Walter Balmer (a Swiss gemologist who visited the area just prior to us), confirmed that Mayote and Chipa (the two neighboring areas) also produce rubies, pink sapphires and blue spinels, with both primary and secondary deposits being worked.

The road from Mahenge to the Ipanko spinel mines. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Joel's jewels

We left Lukande at midday. This was but a snack. Our real meal would be at Ipanko, where several giant spinel crystals had been unearthed just two months prior. We were told that four giant crystals weighting 52, 28, 20 and 5.7 kg were mined there, all from the "Joel Box," named after the lucky miner who first discovered stones there. While these spectacular specimens were lower quality in their centers, outer portions were just beyond superb, yielding clean faceted red stones from 10 to nearly 50 carats.

This incredible 52-kg crystal of spinel was discovered in the summer of 2007 at Mahenge's Joel Box. So big, it was split into smaller pieces for easier transport. The resulting stones from this and a number of other giant spinels found at the same time set off a spinel boom that continues to this day. Photo courtesy of David Weinberg, Multicolourgems.com

Eerily similar to Burma's Mogok Stone Tract, weathered marble outcrops tower over the spinel diggings of Ipanko, near Mahenge. In terms of quality, the gems recovered are also kissing cousins. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

During our visit we witnessed mining at the location where the large crystals were found. A company named "Interstate Mining & Mineral Tanzania Ltd" was working the area. We visited also the hard rock spinel mining area just nearby, where spinels are mined from marbles in association with blue apatite and clinohumite.

A miner at Ipanko holds a fragment of spinel. Photo: Michael Rogers

.jpg)

Miners at Ipanko work the spinel-bearing marble. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

Just a few days after our visit, mining stopped at Ipanko, due to the conflict regarding mining rights. Later, we learned that in November and December 2007, as a result of these difficulties, many miners left Mahenge for a new spessartine deposit near the Serengeti and to the then-new "ruby rush" at Winza.

The fruit of excruciating labor, a handful of fine red spinels from Ipanko, near Mahenge. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Eric Saul displays a spectacular red Mahenge spinel, cut from one of the large crystals found in the summer of 2007. Among connoisseurs, the finest Mahenge spinels have acquired a reputation second-to-none. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

October 11: Mahenge to Songea

Again, up early (anyone see a pattern developing here?), we left Mahenge for the 15-hour drive to Songea. In addition to sapphire, Songea is known for producing coffee and tobacco.

October 12: Songea

The following day we started with a visit to the office of the region's mining officer to get permission to visit the sapphire mines near Kitai (anyone see a pattern here?). Gem mining in Songea takes place near the villages of Ngembambili and Masuguro, while gem trading is concentrated in downtown Songea, where at the time of our visit about ten Thai buying offices were to be found. There are usually two Thai buyers per office, working with three-month business visas. African dealers buy stones from the miners at Masuguro and Ngembambili and then travel to Songea to sell to the Thais. Foreigners are usually not welcome at the mines, as African dealers are afraid the foreigners will try to bypass them and buy directly from miners.

The Franco-Mada love bunny along with his side kick feeling quite at home in Ngemba Ngembambili, Songea. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

About 150 African traders are the link between the 2000 people living at the mines and the 20 to 30 Thai buyers. Fifty so-called "town brokers" live in Songea and travel daily to the mines, while about 150 smaller brokers "bush brokers" live and work at the mines with the miners and, in fact, work for the "town brokers."

Fewer buyers were found in 2007 compared with VP's visit in 2005, as the number of miners in the Songea region had decreased. Locals told us this was mainly due to Thais no longer paying as much as in the past for the stones. Africans complain that the Thais are working like a syndicate to control the prices, while the Thais complain that the market for Songea material is bad, since most stones have to be treated with beryllium in order to be sold. At the time of our visit, prices of Songea beryllium-treated sapphires were quite low and many Thai dealers had stopped buying.

Sapphire miner at Ngemba Ngembambili, Songea. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Local miners stated that the Songea mining area was discovered in 1991, when a local farmer gave some stones he found in his rice field to Indian and Arab rice dealers in Songea town. They later sold these stones to Thai gem dealers in Dar Es Salaam and the rush was on.

The first Thai gem buying office opened in 1992 and mining boomed until 1994, when sapphire and chrysoberyl were found at Tunduru. In 1999, Thai and Sri Lankan buyers left Tunduru for the then-new sapphire deposit at Ilakaka (Madagascar). By 2002, many Thai buyers had returned, following the discovery of beryllium heat treatment for Songea sapphire. Miners told us the prices then given by the Thais were good and more than 6000 miners were eventually working in Ngembambili, but in 2007 we found fewer than 3000 miners in the whole area.

Rough Songea sapphire. Songea stones tend to be grayish green in color, with the occasional purple and yellow stone, along with some ruby. Most of this material is destined for beryllium treatment. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

In our experience, this is not unusual: people start as miners and, if fortunate enough to get good stones, then become brokers. Some will spend this money buying cars, houses and cell phones, while the wisest often invest in other businesses and rapidly refocus on their new activities. Few miners and dealers seems to put their money back into mining, for it is backbreaking work and a business that depends much on luck. If, due to lady luck, it is possible to rapidly get rich in the gem business, it's also possible to lose a fortune at an equal speed. This is the "gem casino."

Mining sapphire at Ngembambili Amanimakoro, Songea. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

In the Masuguro area, two mechanized mines operate. One, Thanistar Mining Co. Ltd. is run by Mr. Prayun, a well-known Thai miner who has also worked in Lukande (near Mahenge). The other, World Gem Supply, is run by an Australian, Brad Mitchell. Visiting Thanistar on October 13th, we were told that the company was not currently producing gems, as it was moving its mining operation 6 km north of their then-current location.

.jpg)

Like grandfather, like grandson

Michael Rogers examines a ruby at Ngemba Ngembambili, Songea. Michael is the grandson of Richard Hughes' mentor, Gerry Rogers. Photo © Vincent Pardieu

During our 2007 trip, we focused on the Ngembambili mining area, and visited two quite different mining areas at Ngembambili Amanimakoro and Ngemba Ngembambili.

At one mine, the owner supplied miners with tools and food. Diggers would then get a 25% cut on the sale of all stones found. At another, the owner provided no food or tools and miners took a 75% share of sales. Finally, at yet another mine, the owner took 30%, with a business sponsor (usually a 'town broker' or Thai dealer) providing food and tools to miners in exchange for a 30% cut, with miners taking the remainder.

At Ngemba Ngembambili, miners were working an alluvial deposit, which is typical in the Songea area. Sapphires are found as slightly rounded pebbles in a gravel layer, with stones being clean with few fissures.

A mud-spattered sapphire miner at Ngembambili Amanimakoro, Songea. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

At Ngembambili Amanimakoro, sapphires are not found in gravel layers, but instead in veins associated with schorl from a white kaolin-like weathered body. The sapphires, which can be purplish to green or yellowish (and rarely red), are usually coated with what looks to be a mica-like crust. Fractures are common in this material, but otherwise similar to the stones found at Ngemba Ngembambili. Thus it appears that if the deposit at Ngemba Ngembambili is secondary in nature, Ngembambili Amanimakoro could be a weathered primary deposit. Geologists might be able to confirm these observations from the photos we've taken and the geologic samples we collected at the mines.

Straight from the ground, Songea sapphires from Ngembambili Amanimakoro (Songea) are often coated with a clay crust. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

October 13: Songea to Tunduru

In the afternoon, we departed Songea for a five-hour drive to Tunduru, one of the major objectives of our expedition. The rough-and-ready mining town of Tunduru is famous for cashew nuts, tsetse flies and man-eating lions, in no particular order. What can we say? It's gem country.

.jpg)

The road from Songea to Tunduru. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

Indeed, our dependable companion, the Rough Guide to Tanzania, stated the following:

Apart from terrible roads, Tunduru district's other claim to ignominy is its man-eating lions (for which reason you should avoid camping wild, and, if you've broken down, stay close to your vehicle while awaiting help). The gruesome attacks have been occurring on and off for three decades, even in town – in 1986, a single lion claimed the lives of 42 inhabitants before stopping its killing spree.

– Jens Finke (2006) The Rough Guide to Tanzania

Lion researcher Dr. Rolf D. Baldus had this to say:

Occasionally in the South of Tanzania there are even killing sprees which go on for a period of time. People are regularly snatched by lions within Tunduru town and there are areas where people are generally advised not to leave their huts after sunset. In Tunduru District, 42 people were killed in 1986. This included even the district Game officer who lost his life at night within Tunduru town.

– Rolf D. Baldus, 2004

.jpg)

Road thrill

On the road from Songea to Tunduru we passed near Namtumbo, which produces aquamarine. Stopping briefly, a gentleman produced a handful of samples. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

Gem mining started in Tunduru about 1994, when the well-known Swiss gem dealer, Werner Spaltenstein (locally known as Malapa) was shown a parcel of rough in Arusha:

In September, 1994, Werner Spaltenstein, a Swiss national, was buying gems in Arusha in northern Tanzania when a broker showed him a small parcel of rough. Werner realized that he had never seen such rough before in Africa. It looked like Sri Lankan rough—blue and yellow sapphire, geuda sapphire, chrysoberyl, spinel, garnet and zircon.

The broker informed him that the rough was obtained from two men who lived in the town of Songea (l0.42 S. 35.39 E.) in southwest Tanzania. Werner immediately hired a car and driver and drove all night to Songea. The next day, he located the two men in Songea, and they directed him to the Mtetesi River about 40 km east of the town of Tunduru. After driving through a plantation and then walking for 30 minutes, they found ten men working the river at the first rapids, which is about 20 km south, down river below where the bridge crosses the Mtetesi river. This location is about 10 km north of where the Mtetesi River intersects the Muhuwesi river.

The men, mostly farmers from the area, were working the river for the gem gravel. They said that as many as 70 men had been working recently, but most gave up as they were unable to sell the gem rough. Werner told them that he would buy the rough. The reason that they could not find a ready market for the rough is that the local buyers were not familiar with this type of rough, much of which was corundum that needed to be heat treated to bring out the colour.

This started the influx of miners and brokers to the area that peaked at approximately fifteen thousand.

– Murray Burford, 1998, Gemstones from Tunduru, Tanzania

It was not long before Tunduru became one of the most active gem-mining areas in Tanzania, with thousands of people digging, selling, buying or supplying miners. The action peaked in 1995–96 with foreign buyers and investors flocking to Tunduru to buy sapphires, rubies, alexandrites and chrysoberyls.

Sadly, certain Tanzanian officials reportedly created problems for both investors and foreign buyers, putting restrictions on the use of machinery, or blocking them while soliciting bribes. Foreigners were also reportedly harassed by local immigration officials, not to mention the security concerns in Tunduru's remote areas.

Foreign buyers from Sri Lanka and Thailand set up in Tunduru town (top), while Tanzanian brokers work the bush in places like Majimaji (below). Photos: Richard W. Hughes

In 1999, following the discovery of sapphire at Ilakaka in Madagascar, nearly all the buyers deserted Tunduru and its difficulties; within a few months, Tunduru's miners and brokers were left without a market for their gems. Thus miners abandoned Tunduru, returning to their farms or migrating to other mining areas like Ruangwa, where tsavorite had been found.

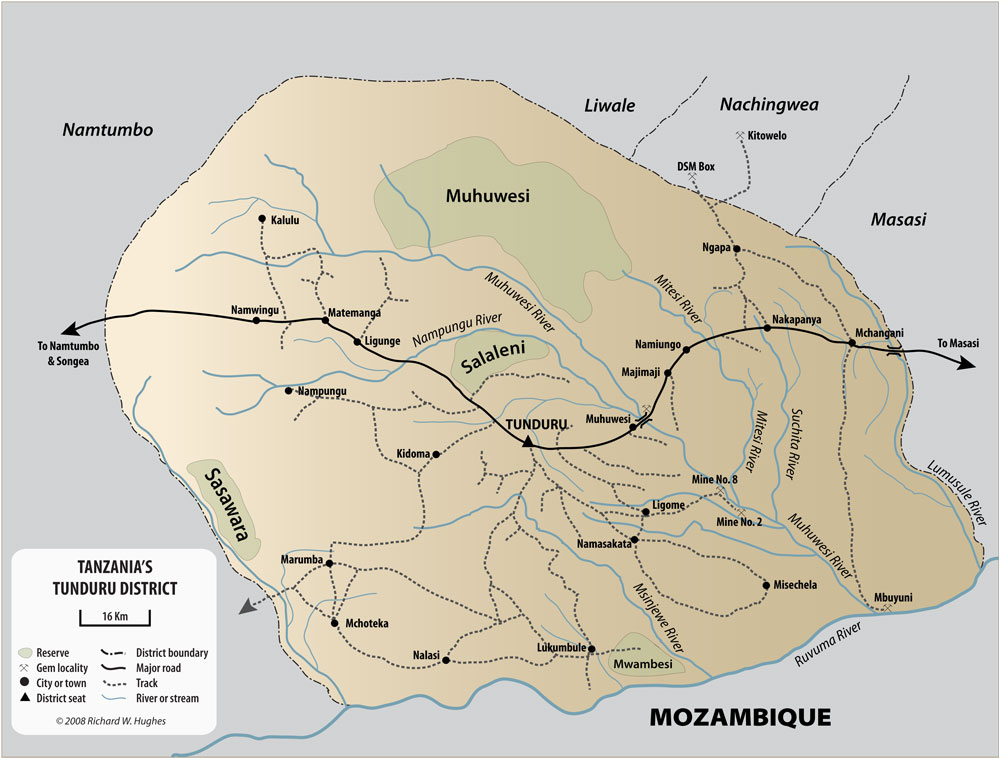

Map of the Tunduru region, showing the major mining districts. Map: Richard W. Hughes

Lay of the land

As of 2007, gem mining was found in a wide area around Tunduru from the Selous Game reserve in the north, to the Ruvuma river in the south (which forms the natural border with Mozambique). Most mining takes place east of Tunduru, along the Muhuwesi, Mtetesi, Lumesule, Mbwenkuru and Ruvuma rivers. All the mining areas we visited in 2007 were alluvial in nature. We never heard of gems being taken from primary deposits, but several people (including Tunduru's mining officer) believed that Tunduru's gems possibly originated in the Muhuwesi Hills to the north (the southern part of the Selous Game Reserve which is the origin of Tunduru's gem-bearing rivers). But this is just a theory.

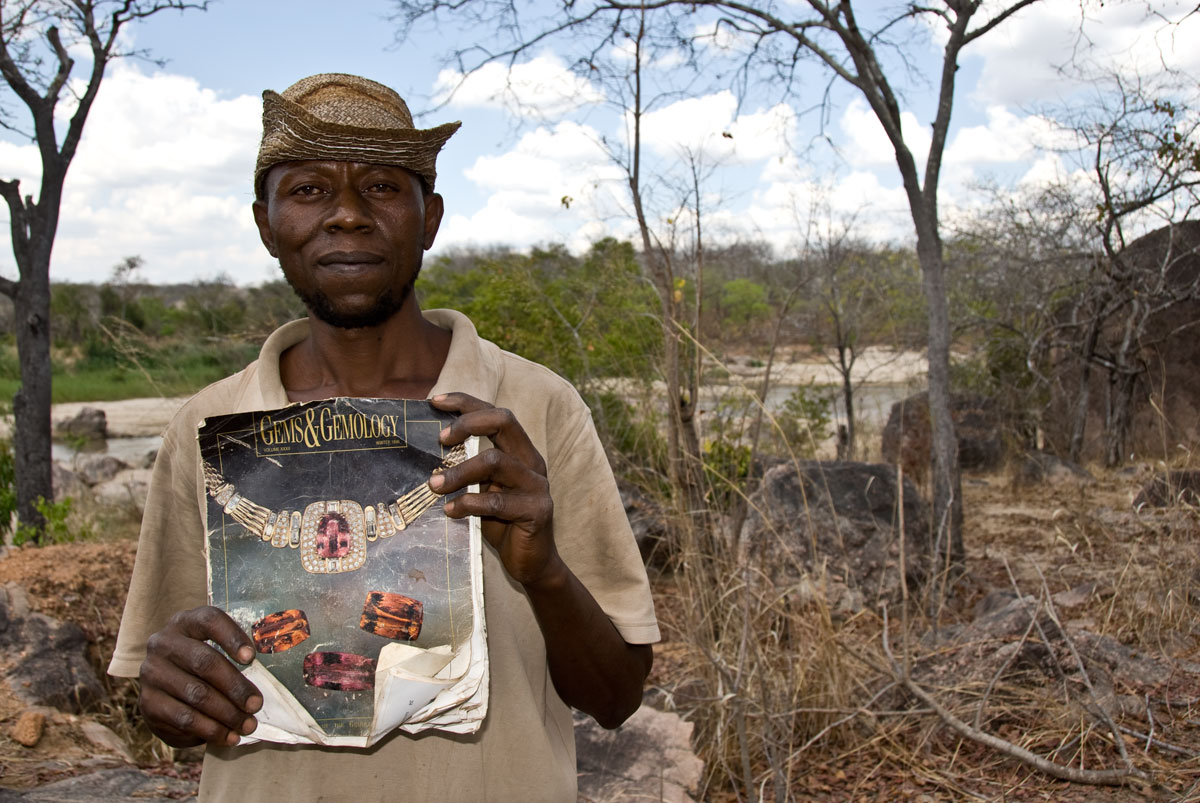

Miner Joseph Mayunga displays one of his prize possessions, a Gems & Gemology magazine that includes an article on the gems of Tanzania, given to him by a Sri Lankan dealer after a successful chrysoberyl deal. At the time of our visit in October, 2007, Joseph had been living and mining at the Muhuwesi river for more than seven years. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Mining in Tunduru is seasonal. When VP first visited the area in August 2005, water levels in rivers were still high. People were found mining a few hundred meters from the Muhuwesi river, collecting gem gravels that were later taken to the river for washing. This type of mining is typical of the wet season mining. Later, in the October 2007 dry season, we witnessed mining mostly taking place in the dry beds of the river, as water levels had receded.

In Tunduru's wet season (December to July), most people are involved in farming rice, corn or vegetables, with little mining taking place. Due to the rains, the work is dangerous, as the ground is not dry enough; pits and tunnels are subject to collapse and miners risk being buried alive.

During the August–November dry season, the main activity in the Tunduru region is cashew nut farming and gem mining. As soon as the rains stop in August–September, the work force is busy in the cashew plantations. Mining is at its highest point during the driest months of October and November.

.jpg)

Miners work the dry riverbed at the Muhuwesi river in Tanzania's Tunduru district. River mining at Muhuwesi river can be difficult work; to reach gem-bearing gravels it is sometimes necessary to break large rocks and even then the mine production can be weak. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

Tunduru's gem trade is well-organized. Foreign buyers concentrate in Tunduru itself and are not allowed to buy gems at the mines or at the local Tanzanian trading center at Majimaji. We found ten Sri Lankan, two Thai and three local Tanzanian gem buying offices open in downtown Tunduru.

At Majimaji, a small trading village an hour's drive east of Tunduru, we were told that seventy brokers were operating. Fifty-two were members of the Majimaji Mining Group (the local Tanzanian gem trader association) and twenty operated outside the association.

Bush meat

Tunduru sapphires (along with a green garnet) from the Ruvuma river that forms the border between Tanzania and Mozambique. While the sapphire color range is quite similar to that in Sri Lanka, the occurrence of green garnet distinguishes Tunduru gravels from those of Ceylon. In addition, the Tunduru gravels are almost completely waterworn, whereas in Sri Lanka, euhedral crystals are commonplace. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

As Majimaji is located between the Muhuwesi and the Lumesule rivers, it is a convenient spot for miners to sell their production. Majimaji's gem traders will then sort the gems and create parcels. We were told a broker could collect about 500 grams of sapphire in 1–3 months. Parcels are then typically sold to the Tunduru foreign buyers or to visiting buyers like the famous Malapa (Werner Spaltenstein). During our days in Tunduru, we encountered a wide variety of gemstones, including chrysoberyl (yellow & alexandrite), sapphire (blue, purple, yellow and pink), ruby, topaz, quartz, garnet (including tsavorite), spinel, and even diamond. Tunduru is also the source of a rare mint-green chrysoberyl that is colored by vanadium and displays no color-change (Johnson & Koivula, 1996b).

Monty Chitty (foreground) and his son, Warne, along the Muhuwesi river in Tanzania's Tunduru district. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

October 14: Exploring Tunduru

On October 14th, following the standard pow wow with the local mining officer, we left to explore the Muhuwesi River, which was the spot where mining first began in 1994. Several mining operations were found at spots No. 2 and No. 8.

As it was the dry season, mining was taking place in the river. First a small dam is commonly built to evacuate water from the river bed. Then workers remove sand to reach the gem-bearing gravels. This operation can take a week. In order to avoid flooding in the pits, it is necessary to use pumps. The gravels collected are then washed to retrieve the gems.

Most miners are poor farmers without the necessary tools and capital to work such river mines. Thus pumps, gas, food and tools are provided by a sponsor (typically a Sri Lankan), not unlike what we encountered in Songea.

.jpg)

Drink up

Warne Chitty with a group of friendly natives along the Muhuwesi river in Tanzania's Tunduru district. Chitty, from Aspen, Colorado, had recently graduated from GIA. At the time of our field trip, he was studying for his FGA, but he and his father were able to join us in Tanzania. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

.jpg)

Hot stuff

Richard Hughes examining a sapphire in Tanzania's Tunduru district. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

Miners fording the Ruvuma river that separates Tanzania (near bank) from Mozambique (far bank), in Tanzania's Tunduru district. Gems are found on both sides of the river. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

October 15: By the Ruvuma

A man returning from his field in the evening was killed by a leopard. Then a lion came, chased away the leopard and ate the victim. My friend C.T returning from the village of Magazini near the Ruvuma in March 2004 (from Baldus, 2004)

Setting out early, we took the tsetse-infested bush road to the Ruvuma River and the Mozambique border to witness the gem mining in that area.

Early 20th century photo of the Ruvuma ('Rovuma') river. Despite the passage of nearly a century, little has changed. Photo from Calvert (1917); from the William Larson Collection

After several hours we reached Mbuyuni village, reportedly the major gem trading center on the Mozambique border. At the river, there were several small trading huts, but few were occupied by buyers. Going a bit further, we found a small mining operation where six diggers were working. This was one of the most fascinating locales in the Tunduru District, where production was composed of the same mix of gemstones we saw the day before on the Muhuwesi river, except the stones were smaller and more tumbled, probably meaning we were farther from the original source. But as Namibian diamond miners (and Ken Kesey) know all too well, further is not necessarily a bad thing. As you stray from the source, the quality of the recovered stone gets better, due to the natural weathering process that removes imperfections.

The Insane Gem Posse in Majimaji, enjoying a few semi-cool ones after a hard day beating the bush for sapphires along Tunduru's Ruvuma River. Left to right: Vincent Pardieu, Richard Hughes, Monty Chitty, Warne Chitty, Michael Rogers and the Franco-Mada love bunny, Guji Soubiraa. Photo: Philippe Brunot

October 16: Lumesule and the DSM Box

On October 16 we left Tunduru (early, right?) to visit mining areas on river Lumesule, with our main objectives being areas the "DSM Box" and Kitowelo.

Gems were reportedly first discovered there in 1995 by a local fisherman, about a year after the discoveries along the Muhuwesi River. We were told that the "DSM box" on the Lumesule River was among the most active Tunduru gem mining localities from 1995–98, with approximately 10,000 miners. At the time of our visit, however, this remote locale was past its boom, with only about 100 huts and 300 miners.

The DSM Box was the the scene of some "difficulties." Not more than a few minutes after our arrival, a "skin tax" was assessed, but following discussion with the village elders, this was thankfully rescinded. Given the green light, we walked to mines in the riverbed of the Lumesule and a "land mine" about 300 meters from the river.

Sadly, the good feelings expressed by the village elders did not carry over to their offspring. Upon returning to our Land Cruisers, we were greeted by a mob of angry people led by an agitated youngster, still demanding the skin tax. Seeing the village youth wielding rocks and sharpened sticks, we quickly understood that, while the wisdom of elders is of eternal value, there are times and places where one must give precedence to the new generation. Thus, in the spirit of supporting the local economy and community youth, we quickly coughed up the skin tax and beat a hasty retreat.

Following this adventure (along with a bit of attempted highway extortion further on), we arrived at Kitowelo, famed as the home of Tunduru's biggest blue sapphires and alexandrites. Here we learned of gem-quality blue sapphires up to 30 carats and an alexandrite weighting an incredible 36 grams in the rough.

Kitowelo's mines were reportedly discovered in 1995. From 1995 to the beginning of October 2007, a large Thai operation with machines was present, but just days before our visit, Mr. Prayun (the Thai miner who is also mining in Songea) moved his equipment to his new project at Masuguro, Songea. The number of miners had thus dropped within days from 300 to just 100.

After Kitowelo, we drove to Masasi, arriving late at night. It had been a long day and a longer trip, leading RWH to declare: "Vince, when I get home from this 'vacation,' I'm gonna need a vacation."

|

The gemological features of Tunduru sapphire Following our visit to Mahenge, Songea and Tunduru, one of the junior members of our team, Warne Chitty, set to work on a thesis suggested by RWH, that of detailing the gemological features of the sapphires of Tunduru. In many respects, Tunduru was the proverbial blank spot on the gemological map, and Warne Chitty has now helped fill in some of the missing details. His work is important and can be downloaded here:

by Warne Chitty |

Bad Boy No. 1 at Tunduru's No. 2 Box along the Muhuwesi River. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

Down by the river

He described how, as a boy of 14, his dad had been down the mining pit, his uncle had been down the pit, his brother had been down the pit, and of course he would go down the pit. Barbara Castle

When Tunduru's mines were first discovered, a rush started. Remarkably, miners did not even have the means to pay for bus transport from Songea to Tunduru. So they did what so many in the Third World do: they walked. They walked nearly 300 km, through some of the baddest bush in all of the bad badlands of East Africa. There was no other choice—this was the land in which they lived.

One day in Tanzania's Tunduru district, we were exploring along the Muhuwesi river. A young boy of about twelve years watched with curiosity as we scraped and gathered tiny fragments of gems left behind by the miners. Soon he was helping us in our quest. As we made ready to leave, he asked if he could hitch a ride to his village. We agreed and, on the way back, had a chance to get to know him better.

He told us that every day he would walk more than ten kilometers down to the river in hopes of finding a few small gems. We asked why. This is the story he told:

When I was younger, my family had no money for food and so my father stole something in the market and was caught and imprisoned. To support our family, my mother became a prostitute and later contracted HIV. When my father was released, the disease passed to him. Now both are dead. Today I live with my grandmother and go down to the river every day.

Third World calling

The desire of gold is not for gold. It is for the means of freedom and benefit. Ralph Waldo Emerson

Sadly, such a story is all too common in many developing nations. This is the land in which they live. Gem mining provides them a shot at something better. It's a distant shot—perhaps less than one in a million—but a shot nonetheless. For those who have rolled snake eyes all their lives, even a lottery ticket looks good. It doesn't mean they have bad math skills, it simply means it's the best game in town—in their town. This is not a job. This is work. This is the life they live.

When one pushes niceties and manners aside, for many on this planet, life is survival. Not a reality TV show, but the real world of waking up each day and wondering where they will get the means to reach the next dawn. This is life broken down into its most basic form. This is work.

A handful of hope in Tanzania's Tunduru district. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Gold Mountain

Walk on, talk on, baby tell no lies.

Don't you be caught with a tear in your eye. Neil Young, Come On Baby Let's Go Downtown

What is work? Years ago, one of the authors had a conversation with a lady about that. Once married, she and her young child had been abandoned. How did she feel? She had absolutely no shame. "I'm all cried out," she declared. "I have no more tears."

So powerful. She discarded petty shame and sorrow, but kept hope. In doing so, she slipped karma's leash.

She was a working girl.

Is it karma for an infant to begin life with a death sentence, for a father to be so poor he must rob? Is it karma for a mother to sell what she can so her family survives? Truly, what is karma?

Some have free will, but for those with just a roulette-wheel-chance, karma is abstract. Digging holes in the ground? This is possible today. This is real. Strike it rich.

We know of a land where that happened. A place filled with every societal ill, but still full of people ready to work and full of hope.

Step forward a century and a half and those peoples' hopes have been vindicated. That once-poor place is now the world's eighth largest economy. You might have heard of it. The Chinese call it Jin Shan—Gold Mountain—but today it's known by a better name—California.

And yet surely to alchemy this right is due, that it may be compared to the husbandman whereof Æsop makes the fable, that when he died he told his sons that he had left unto them gold buried under the ground in his vineyard: and they digged over the ground, gold they found none, but by reason of their stirring and digging the mould about the roots of their vines, they had a great vintage the year following: so assuredly the search and stir to make gold hath brought to light a great number of good and fruitful inventions and experiments, as well for the disclosing of nature as for the use of man's life. Francis Bacon

The Advancement of Learning (1605)

Giant steps

So many miners are poor, but despite their poverty, they are proud of what they do. While driven by luck, they understand the odds. Despite the difficulties, as they toil underground, they maintain hope there will always be a light shining above.

Step back—away from the road—beyond the map. As you do so, you'll notice something. Many in this world have money, but are still miserable. And yet others—possessing so little—confound poverty's sadness with their happiness. Hope separates poverty from misery. Hope slips karma's leash. This is why the young boy went down to the river every day.

In the course of our travels downtown we discovered many gems. But this lesson was genuine treasure—something just beyond priceless.

River of dreams

A young boy along the Muhuwesi River with a handful of gems. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Postscript—The working hour

I don't like work – no man does, but I like what is in the work, the chance to find yourself. Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

The above is about work—what we do in that space between birth and death. Each of us who enters life walks the same tightrope.

Sadly, some slip sooner than others. Two years after our Tunduru adventure, our guide, companion and friend, Abdul Amsallem, whose knowledge of Tanzania's gem mines was second-to-none, disappeared on a gem-scouting trip in Mozambique. He has not been heard from since. Abdul, we hope you are still out there somewhere, going down holes, hunting gems, still searching and still dreaming…

Our guide and friend, Abdul Amsallem. Photo: Vincent Pardieu

|

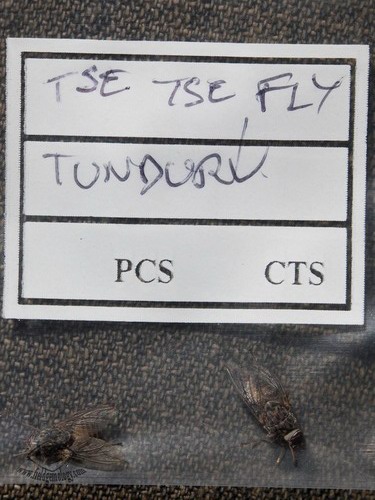

Beasty Boys: East Africa's Wildest Wildlife The East African bush is home to a number of lovely beasts, including the tsetse fly, the safari ant, and larger pests such as the black mamba. We were to have brushes with all. Tsetse are large biting flies from Africa which live by feeding on the blood of vertebrate animals. They are infamous as carriers of the African trypanosomiases, deadly diseases that include sleeping sickness in people and nagana in cattle. We sent a number of them into the hereafter along the Ruvuma river. Kill them all; god will know his own.

VLT –Vicious Little Things. Tsetse flies collected in Tanzania's Tunduru district. Photo © Vincent Pardieu Another fine piece of pestilence is the safari ant, which RWH met up with while stopping for a picture at Ipanko, in the Mahenge region. Stepping back into the jeep, the human occupants were greeted by the sight of RWH launching skyward like a Scud missile as a number of smaller guests made their presence felt. The soldier type of this ant features oversized jaws of such strength that the Masai use them as emergency bush sutures, allowing the ants to bite both sides of the wound and then breaking off the body to seal it shut. The safari ant (Dorylus) is a particularly pernicious pest. This example is making a bee-line for RWH's gonads. Photo © Richard W. Hughes Fortunately our encounter with the deadly black mamba followed its expiry date, having minutes before been walloped to death by a villager's stick. Which was a good thing, for a single bite from this serpent contains enough venom to kill scores of adults. According to the Wikipedia: Black mambas are among the ten most venomous snakes in the world. Black mamba venom can kill a human in 20 minutes… The initial symptom of the bite is local pain in the bite area, although not as severe as snakes with hemotoxins. The victim then experiences a tingling sensation in the extremities, drooping eyelids (eyelid ptosis), tunnel vision, sweating, excessive salivation, and lack of muscle control (specifically the mouth and tongue). If the victim does not receive medical attention, symptoms rapidly progress to nausea, shortness of breath, confusion, and paralysis. Eventually, the victim experiences convulsions, respiratory failure, and coma, and dies due to suffocation resulting from paralysis of the muscles used for breathing. Without treatment the mortality rate is nearly 100%, among the highest among venomous snakes. I think you get the idea. The black mamba is one badass bit of tubular trouble.

A black mamba in Tanzania's Tunduru district, just past its expiry date. Photo © Richard W. Hughes But of all the varmints of East Africa, none takes a greater toll on the human population than the female Anopheles mosquito, which carries deadly malaria. Each year, more than 500 million people are infected, with more than a million deaths per annum. While medicines are available to treat the disease, for so many of the poor, the best protection is simple: mosquito nets. An organization has been set up to help deliver this life-saving protection. This campaign by well-known sports writer (and ex-school mate of RWH), Rick Reilly, was begun following his visit to East Africa: A few years back, we took the family to Tanzania, which is ravaged by malaria now. We visited a school and played soccer with the kids. Must've been 50 on each team, running and laughing. A taped-up wad of newspapers was the ball and two rocks were the goal. Most fun I ever had getting whupped. When we got home, we sent some balls and nets. – Rick Reilly, Sports Illustrated, May 1, 2006 NothingButNets.net has been set up to deliver mosquito nets to Africans in need. Click on the banner below to help. |

References & further reading

- Altherr, R., Okrusch, M. et al. (1982) Corundum- and kyanite-bearing anatexites from the Precambrian of Tanzania. Lithos, Vol. 15, No. 3, Sept., pp. 191–197.

- Anonymous (1989) Thai joint venture gets Umba exclusive. Colored Stone, Vol. 2, No. 4, p. 25.

- Baldus, R.D. (2004) Lion conservation in Tanzania leads to serious human-lion conflicts, with a case study of a man-eating lion killing 35 people. Tanzania Wildlife Discussion Paper, No. 41, 64 pp.

- Bank, H. (1963) Zoisitamphibolit mit Rubin aus Tanganjika (Ostafrika). Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Edelsteinkunde, No. 44, pp. 4–11.

- Bank, H. (1970) Hochlichtbrechender Orangefarbiger Korund aus Tansania. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Vol 19, pp. 1–3.

- Bank, H. (1971) Über einige Edelsteine aus Tansania und ihre Vorkommen. Hessisches-Landesamt für Bodenforschung, Abhandlungen, Vol. 60, pp. 203–215.

- Bank, H. (1971) Edelsteinvorkommen in Afrika. Afrika-Spektrum, No. 2/1970, pp. 96–110, 124–127.

- Bank, H. (1974) Smaragd, Alexandrit und Rubin als Komponenten einer Paragenese vom Lake Manyara in Tansania. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 23, No. 1, März, pp. 62–63.

- Bank, H., Berdesinski, W. et al. (1967) Strontiumhaltiger trichroitischer Zoisit von Edelsteinqualitat. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Edelsteinkunde, Vol. 61, pp. 27–29.

- Bank, H., Berdesinski, W. et al. (1972) Violette edelkorunde aus dem Umba-Geviet von Tanzania. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 21, pp. 126–127.

- Bank, H. and Henn, U. (1988) Rubies of cuttable quality from Ngorongoro in Tanzania. Börsen Bulletin, 12/88, p. 102.

- Bank, H. and Henn, U. (1990) New sources for tourmaline, emerald, ruby, and spinel. ICA Gazette, April, p. 7.

- Bassett, A.M. (1993) Gemstones of East Africa [book review]. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 29, No. 3, Fall, p. 217.

- Bridges, C.R. (1982) Gemstones of East Africa. In International Gemological Symposium Proceedings, Santa Monica, CA., Gemological Institute of America, pp. 266–275.

- Burford, M. (1998) Gemstones from Tunduru, Tanzania. Canadian Gemmologist, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 105–110.

- Calvert, A.F. (1917) German East Africa. London, T. Werner Laurie, Ltd., 122 pp., 219 plate.

- Clanin, J. (2006) Geology and mining of Southern Tanzanian alluvial gem deposits. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 42, No. 3, Fall, p. 107.

- Crowningshield, R. (1962) Developments and Highlights at the Gem Trade Lab in New York: Odd-color sapphires and rubies [from Tanzania]. Gems and Gemology, Vol. 10, No. 11, Fall, p. 340.

- Dirlam, D.M., Misiorowski, E.B. et al. (1992) Gem wealth of Tanzania. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 28, No. 2, Summer, pp. 80–102.

- Dissanayake, C.B. and Chandrajith, R. (1999) Sri Lanka–Madagascar Gondwana linkage: Evidence for a Pan-African mineral belt. Journal of Geology, Vol. 107, pp. 223–235.

- Du Toit, G., Charoensrithanakul, S. et al. (1995) Lab Report: Synthetic flux rubies; color change sapphires; irradiated yellow star sapphire; synthetic hydrothermal ruby. JewelSiam, Vol. 6, No. 4, Aug–Sept, pp. 106–110.

- Eliezri, I.Z. and Kremkow, C. (1994) The 1995 ICA world gemstone mining report. ICA Gazette, December, p. 1, 9 pp.

- Federman, D. (1988) Modern Jeweler’s Gem Profile: The First 60. Shawnee Mission, Kansas, Modern Jeweler, Photos by Tino Hammid, 131 pp.

- Federman, D. (1990) Consumer Guide to Colored Gemstones. New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 253 pp.

- Finke, J. (2006) The Rough Guide to Tanzania. London, Rough Guides, 2nd ed., 816 pp.

- Game, P.M. (1954) Zoisite-amphibolite with corundum from Tanganyika. Mineralogical Magazine, Vol. 30, pp. 458–466.

- Giménez, G. and Leguey, S. (1990) Saphirs et rubis de Tanzanie. Revue de Gemmologie, a.f.g., No. 102, pp. 6–8.

- Giuliani, G., Fallick, A. et al. (2007) Oxygen isotope systematics of gem corundum deposits in Madagascar: relevance for their geological origin. Mineralium Deposita, Vol. 42, No. 3, February, pp. 251–270.

- Gübelin, E.J. (1973) Internal World of Gemstones. Zürich, ABC Verlag, reprinted 1983, 234 pp.

- Gübelin, E.J. (1981) Einschlüsse im Granat aus dem Umba-Tal. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 30, No. 3/4, pp. 182–194.

- Gübelin, E.J. and Graziani, G. (1980) Observations faites sur quelques scapolites de Tanzanie centrale. Revue de Gemmologie, a.f.g., No. 65, December.

- Gübelin, E.J. and Graziani, G. (1981) Observations on some scapolites of central Tanzania. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 7, No. 6, April, pp. 395–405.

- Gübelin, E.J., Graziani, G. et al. (1983) Observations on some scapolites of central Tanzania: Further investigations. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 18, No. 5, January, pp. 379–381.

- Gübelin, E.J. and Koivula, J.I. (1986) Photoatlas of Inclusions in Gemstones. Zürich, Switzerland, ABC Edition, revised Jan., 1992; German edition, 1986 (Bildatlas der Einschlüsse Edelsteinen), 532 pp.

- Gübelin, E.J. and Schmetzer, K. (1982) Eine neue Edelstein-Varietät aus Tansania: Gelbe, grüne und rötlich-braune Apatit-Katzenaugen. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 261–264.

- Gübelin, E.J. and Schmetzer, K. (1983) A new gemstone variety from Tanzania. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 18, No. 7, July, pp. 592–595.

- Gunawardene, M. (1984) Reddish-brown sapphires from Umba Valley, Tanzania. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 19, No. 2, April, pp. 139–144.

- Hänni, H.A. (1986) Korunde aus dem Umba-Tal, Tansania. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 35, No. 1/2, October, pp. 1–13.

- Hänni, H.A. (1987) On corundums from Umba Valley, Tanzania. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 20, No. 5, January, pp. 278–284.

- Hänni, H.A. and Schmetzer, K. (1991) New rubies from the Morogoro area, Tanzania. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 156–167.

- Henn, U. and Bank, H. (1991) Rubies of facet-cutting quality from Tanzania. Börsen Bulletin, 6/91, p. 116.

- Henn, U. and Milisenda, C. (1997) Neue Edelsteinvorkommen in Tansania: Die region Tunduru-Songea. Gemmologie: Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 29–43.

- Hunstiger, C. (1989–90) Darstellung und Vergleich primärer Rubinvorkommen in metamorphen Muttergesteinen [Presentation and comparison of primary ruby occurrences in metamorphic rock]. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Part I: Petrographie und Phasenpetrologie, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 113–138; Part II: Petrographie und Phasenpetrologie, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 49–63; Part III: Petrographie und Phasenpetrologie, No. 2/3, pp. 121–145.

- Hughes, R.W. (1997) Ruby & Sapphire. Boulder, CO, RWH Publishing, 512 pp.

- Johnson, M.L. and Koivula, J.I. (1996a) Gem News: Gem materials from the new locality at Tunduru, Tanzania. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 32, No. 1, Spring, pp. 58–59.

- Johnson, M.L. and Koivula, J.l. (1996b) Gem News: Non-phenomenal vanadium-bearing chrysoberyl. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 32, No. 3, Fall, pp. 215–216.

- Johnson, M.L. and Koivula, J.I. (1997a) Gems News: Orange sapphire and other gems from the Tunduru region. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 33, No. 1, Spring, p. 66.

- Johnson, M.L. and Koivula, J.I. (1997b) Gem News: Tunduru-Songea gem fieIds in southern Tanzania. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 33, No. 4, Fall, p. 305.

- Kammerling, R.C., Koivula, J.I. et al. (1995) Gem News: Sapphires from Tanzania. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 31, No. 1, Spring, pp. 64–65.

- Kammerling, R.C., Koivula, J.I. et al. (1995) Gem News: Sapphires and other gems from Tanzania. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 31, No. 2, Summer, pp. 133–134.

- Keller, P.C. (1992) Gemstones of East Africa. Phoenix, Geoscience Press, [with photos by E.J. Gübelin], 160 pp.

- Koivula, J.I. and Kammerling, R.C. (1990) Gem News: East African spinels. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 26, No. 1, Spring, p. 107.

- Koivula, J.I., Kammerling, R.C. et al. (1992) Gem News: Faceted ruby from Longido, Tanzania. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 28, No. 3, p. 203.

- Koivula, J.I. and Kammerling, R.C. (1991) Gem News: Tanzanian spinel. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 27, No. 3, p. 183.

- Koivula, J.I., Kammerling, R.C. et al. (1993) Gem News: Ruby mining near Mahenge, Tanzania. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 29, No. 2, p. 136.

- Meen, V.B. (1968) Zoisite—A newly found gem. Lapidary Journal, Vol. 22, pp. 636–637.

- Meixner, H. (1977) Rubin von Longido, Tansania. Lapis, Vol. 2, No. 8, p. 13.

- Msolo, A.P.B. (1992) Ruby mining in the Morogoro region. SMI (Small Mining International) Bulletin, No. 4, Feb., p. 7.

- Mumme, I.A. (1988) The World of Sapphires. Port Hacking, N.S.W., Mumme Publications, 189 pp.

- Naftule, R. (1982) Gemstones of Africa: Sapphires of Umba. Jeweler & Lapidary Business, May/June, p. 8, 3 pp.

- Oshman, D.C. and Caulton, C. (1979) Colored gems of East Africa. Lapidary Journal, November, p. 1768.

- Pardieu, V. (2007) Tanzania, October 2007—A gemological safari—Part 1: Ruby, sapphire, moonstone, spinels, tsavorite, alexandrite—Gems from central and south Tanzania. Fieldgemology.org.

- Pardieu, V., Hughes, R.W. et al. (2008) Spinel: Resurrection of a classic. InColor, Summer, pp. 10–18.

- Pohl, W.G., Niedermayr, G. et al. (1977) Geology of the Mangari ruby mines. Austria Mineral Exploration Project, Report No. 9, 70 pp.

- Pough, F.H. (1971) Meet Tanzania’s fancy sapphires. Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone, Vol. 142, No. 1, Oct., p. 84, 5 pp.

- Quinn, E.P. and Laurs, B.L. (2004) Gem News: Pink to pink-orange spinel from Tanzania. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 40, No. 1, Spring, pp. 71–72.

- Rutland, E.H. (1963) Corundum and amethyst from Tanganyika. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 9, October, pp. 52–54.

- Rwezaura, M. (1990) Known gemstone deposits in Tanzania. Unpublished manuscript, 27 pp.

- Sarofim, E. (1970) Gem-rich Tanzania. Lapidary Journal, No. 3, June, pp. 434–439.

- Schmetzer, K., Bosshart, G. et al. (1982) Naturfarbene und behandelte gelbe und orange-braune Sapphire. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 31, pp. 265–279.

- Schmetzer, K., Bosshart, G. et al. (1983) Naturally-colored and treated yellow and orange-brown sapphires. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 18, No. 7, July, pp. 607–622.

- Schmetzer, K. and Schwarz, D. (2004) The causes of colour in untreated, heat treated and diffusion treated orange and pinkish orange sapphires – a review. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 29, No. 3, July, pp. 149–181.

- Schwarz, D., Pardieu, V. et al. (2008) Rubies and sapphires from Winza, central Tanzania. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 44, No. 4, Winter, pp. 322–347.

- Solesbury, F.W. (1967) Gem corundum pegmatites in N.E. Tanganyika. Economic Geology, Vol. 62, pp. 983–991.

- Suleman, A., Zullu, A.S. et al. (1994) More gem mining activity in Tanzania. ICA Gazette, December, pp. 3–5.

- Ward, F. (1991) Rubies and sapphires. National Geographic, No. 4, October, pp. 100-125.

- Ward, F. (1992) Rubies and Sapphires. Bethesda, MD, Gem Book Publishers, updated Aug. 1995, 64 pp.

- Webster, R. (1961) Corundum from Tanganyika. Gems & Gemology, Fall, pp. 202–205.

- Weinberg, D. (2007) Giant red spinel crystal discovered in East Africa. Multicolour.com, 5 October.

- Zwaan, P.C. (1974) Garnet, corundum, and other gem minerals from Umba, Tanzania. Scripta Geologica, Vol. 20, pp. 19–30.

- Zwaan, P.C. (1974) Les corundons d’Umba, Tanzanie (extrait). Revue de Gemmologie, a.f.g., No. 39, pp. 21–22.

This says it all, doesn't it? Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who assisted their journey:

We extend gracious thanks to our guide, Abdul Amsallem, whose knowledge of Tanzania's gem mines is second-to-none. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

We extend gracious thanks to Mark and Eric Saul of Swala Gem Traders, who did everything in their power to make our journey a successful one. Photos: Vincent Pardieu

We extend gracious thanks to our drivers, Musa (top) and Abel (bottom), who kept us on the proper path and made sure we did not get into more trouble than we deserved. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

We extend gracious thanks to Kennedy and Susie Kamwathi (center and right) of Kennedy's Gems in Nairobi for all their help with our journey. Photo: Montogmery Chitty.

We also extend our thanks to Nixon Monga, Izrael Deo and Tobias Stanslaus of Merelani's Block D mine.

A very special thanks goes out to Ian Harebottle, Zane Swanepoel, Robert Grafen-Greaney, Gabriella Endlin, Hayley Henning and the rest of the TanzaniteOne and Tanzanite Foundation staff. May all your dreams be true blue!

Meet the Insane Gem Posse…

Vincent Pardieu, a self-confessed "travel-addicted gemologist," lives life for the sole reason that, somewhere, someplace, there still exists a hole in the ground he has yet to put his head into. His personal writings and research can be found at www.fieldgemology.org. We are still looking for a twelve-step program for him. Reader suggestions should be submitted to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Soap required.

Richard W. Hughes (clean, center) claims to be the author of Ruby & Sapphire and a bunch of other crap he says will be important when "they finally get it." So sweet. A committed conspiracy theorist, Richard believes that life is a plot, designed to trick us into believing we are not already dead. If you happen to know "they" or understand what "it" might be, contact Richard at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Anonymous remailer and tin-foil hat required.

Guillaume "Guji" Soubiraa first became interested in precious stones as a teenager in Madagascar. His interest was rekindled upon meeting VP and RWH in Tana in 2005. Soon he was studying gemology in Bangkok and the rest, as they say, is… uh… we'd better not say. A self-confessed Franco-Mada love-bunny, Guji awaits the day that he can pick up "hot American babes" in Aspen. With a smile like that, who can resist? Snowbunnies who would like to jump some "sexy French bones" can contact him at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Toothbrush required.

Michael Rogers is the third-generation of the Rogers family in the gem business, with his grandfather and father being old friends of RWH. His family's company, Rogers Gems, is currently involved in mining in Madagascar (or so they say). Mike is half-Japanese, a quarter Dutch, an eighth Pelé, a bit Indonesian, a sliver Mac, three-thirty-seconds french hen and two hundredths turtle dove. Contact Mike at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Toothbrush and partridge in pear tree required.

Monty Chitty (left) moved to Aspen, Colorado at the encouragement of his late friend, Hunter S. Thompson. His introduction to the insane gem posse was via cryptic screed to RWH on a sheet of old Rangoon Strand Hotel stationery. A torn fragment of a 45-kyat Burmese banknote, with a brief message stating that someone would soon present the missing half sealed the deal. Monty provided adult supervision, good humor and a welcome shoulder to cry upon when RWH learned his house might be burning down. Contact him at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Hip flask and snake venom required.

Warne Chitty (right) began his gemological studies with a trip to Colombia's emerald mines with Ron Ringsrud. Warne now sports a G.G., an F.G.A. and is currently angling for a B.m.F. in Great Britain. His dream job is guiding Guji through Aspen's nightlife scene. Contact him at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Prophylactics required.

Philippe Brunot is a "budding filmmaker." Budding in that he is still learning Rule No. 1: a broken camera does not a film make. If you can believe this, Philippe slipped and fell while fording Tanzania's Muhuwesi River. Ever the hero, he risked life and limb to keep camera dry, and succeeded. But it still stopped working. Philippe is busy combing the bazaars of East African in search of an HD video camera repair shop. If you know of one, please contact him at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Waders required.

Notes

This article is based on Vince Pardieu's 2008 field report, following an October 2007 visit to Kenya and Tanzania. It is the companion piece to "Working the Blueseam: The Tanzanite Mines of Merelani."

A Study of Sapphires and Rubies from Tanzania's Tunduru District

A Study of Sapphires and Rubies from Tanzania's Tunduru District