The chapter on ruby and sapphire from Burma (Myanmar) from Richard Hughes' 1997 book, Ruby & Sapphire.

Note: The following is only one of forty-five studies of world sources found in Chapter 12 of Richard Hughes' 1997 book, Ruby & Sapphire. If you like what you see, order a copy of the revised 2017 edition direct from the publisher.

The quest for precious stones does not rank high on humankind's list of worthy or redeeming activities. You'll find no mention of it in the Boy Scout handbook. And you'll not see it prescribed by priests as a path towards forgiveness, for in the struggle to possess the earth's booty, far too many a sinner is born and even more falsehoods are fabricated. We cannot look to gemstone mining for useful homilies. There is no lesson via process, no consolation in the journey. The only reward is the reward itself – to possess, to claim as one's own. Gem mining's attraction is thus: grasp the purest of the pure, tap God's current, the power of all creation. Hold the earth's bounty in one's own hand… and damn anyone who shall stand in your way.

Anonymous

Figure 1. Dust jacket from the 1960 English edition of Joseph Kessel's Mogok: The Valley of Rubies.

Figure 1. Dust jacket from the 1960 English edition of Joseph Kessel's Mogok: The Valley of Rubies.

Burma (Myanmar) • from Ruby & Sapphire (1997)

Corundum has been found in a number of different areas of Burma. These include Sagyin (near Mandalay), Thabeitkyin, Naniazeik (near Myitkyina), Mogok and, most recently, Möng Hsu (central Shan state). Most famous is the Mogok Stone Tract, which has remained the world's premier source of ruby for more than 800 years.

Far away in a remote corner of the earth is a town of mushroom growth, called Mogok… It has but one industry, the recovery of rubies from mud and sand. You may be ever so hungry or thirsty, the first things offered or mentioned to you are rubies. No matter what business may have brought you to Mogok, the natives all assume you are there for rubies – rubies, nothing but rubies… It is said that a king would be ruling at Mandalay today if it had not been for rubies…

Anonymous, 1905, A city built on rubies

|

Figure 2. Kipling called it a "beautiful winking wonder." It is Rangoon's Shwedagon Pagoda, symbol of Burma, the Golden Land. Ralph Fitch, the great English traveler of the 16th century, described it thus:

In addition to the numerous solid gold plates, the upper reaches are embedded with literally thousands of diamonds and other precious stones. Atop it all rests a 76-ct diamond orb. (Photo by the author, 1980) |

When one speaks of ruby, the Mogok Stone Tract in Upper Burma immediately springs to mind. Lying approximately 644 km (400 miles) north of Rangoon, Mogok has for the past 800 years been the premier source of fine rubies. It is an area steeped in legend and its story embraces not only gems, but also the early exploration and expansion of the European colonial empires into Asia.

The town of Mogok (1500 m) is located in the Katha district of Upper Burma. Consisting of heavily-jungled hills rising to a height of 2347 m (7700 ft) above sea level, the ruby mines district covers about 400 sq miles, although only a portion (70 sq miles) is gem bearing. Considered one of the most scenic areas in Burma, it is home to a number of colorful ethnic groups, as well as a variety of wildlife, including elephants, tiger, bear and leopard.

|

|

| Figure 3. Pigeon's Blood Left: The 196-ct Hixon Ruby of the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History is one of the finest Burmese ruby crystals on public display. Unfortunately, such crystals are all too rare – most are immediately cut, since the market for cut stones is far larger than that for mineral specimens. Right: These extraordinary rubies, at 5.56 and 5.25 ct., represent a lifetime's toil. They are mounted in the traditional Burmese manner, with the gold setting improving the stones' color, as well as acting as a mirror to increase the gems' brilliance. |

|

Figure 4. Map of Southeast Asia, showing the important gem localities, particularly those of Burma.

Figure 4. Map of Southeast Asia, showing the important gem localities, particularly those of Burma.

|

Timeline of ruby and sapphire in Burma Middle PleistoceneRuby is probably discovered in the Mogok region by stone-age humans inhabiting the area. 6th Century ADOne of the seven sons of Kun-Lung, founder of the Shan dynasty, is said to rule a state, probably Momeit,a near which ruby mines existed. His tribute to the central government was two vissb yearly (G.S. Streeter, 1889a). 1200sTalaing chronicles speak of a kingdom of Kanpalan [Kyatpyin?] (Mason, 1850; Halford-Watkins, 1934). 1419–1444Nicolò di Conti visits Ava (Penzer, 1929). 1495–1496Hieronimo di Santo Stefano, a Genoese merchant, visits Pegu. Ava is described as a land lying fifteen days' journey from Pegu. Rubies and many other precious stones are said to "grow" there (Major, 1857). 1500–1517Duarte Barbosa does not visit, but describes Ava and Capelam [Kyatpyin?] and the ruby trade (Dames, 1918). 1502–1508Ludovico di Varthema visits Pegu and describes the source of rubies as Capellan. In return for a present of coral, di Varthema received from the king of Pegu about 200 rubies in return: "Take these for the liberality you have exercised towards me" (Temple, 1928). 1563Cæsar Fredericke visits Pegu, describes the ruby trade, and buys rubies for later sale in Ceylon (Hakluyt, 1903–05). 1586Ralph Fitch, the first Englishman to reach Burma, visits Pegu and describes the ruby trade. He mentions Caplan as the source (Hakluyt, 1903–05). 1597Burmese king, Nuha-Thura Maha Dhama-Yaza forces the Momeik sawbwa (prince) to trade Mogok and Kyatpyin for Tagaungmyo (George, 1915). 1617The British East India Company makes its first contact with Burma, when Henry Forrest and John Staveley are sent to recover the goods of a company servant who had died at Syriam (Stewart, 1972). 1629–1637Fray Sebastien Manrique visits Arakan, where he said the market was well-stocked in such things as rubies, sapphires and even "gray" amber (Luard, 1926–27). 1631–1668Jean-Baptiste Tavernier makes six separate voyages to Asia. Although he does not visit Burma, his memoirs mention that ruby comes from Capelan (Ball, 1925). 1780King Bodawpaya sends thousands of captives from the Manipur war to Mogok, to work the mines. Thereafter the mines become a quasi-penal colony (Halford-Watkins, 1932). 1783King Bodawpaya extends the tract boundaries to encompass Mogok, Kyatpyin and Kathé (Brown, 1927). 1795Michael Symes visits Ava, and mentions ruby mines at a mountain called Woobolootaun opposite to Keoum-meoum (Symes, 1800). 1824–1826The first Anglo-Burmese war is won by Britain. The treaty of Yandabo cedes Arakan, Assam and Tenasserim to the East India Company (Stewart, 1972). 1830A runaway English sailor in the employ of King Phagyidoa is sent to blast a rock at a royal ruby mine at Tapambin. He either died at the mines or slipped quietly away, for nothing was heard of him again (G.S. Streeter, 1889). 1833Père Giuseppe d'Amato, an Italian Jesuit, visits Chia-ppièn [Kyatpyin] and describes the ruby mines. His account (published posthumously in 1833) is the first documented eyewitness description of the ruby mines (d'Amato, 1833). 1852–1853Britain annexes Pegu, which is taken with few losses in the second Anglo-Burmese war (Stewart, 1972). 1853Henry Yule's mission to Ava. He describes, but does not visit, the ruby mines (Yule, 1858). 1853–1878The reign of King Mindon Min. In 1863, payments in silver are offered Mindon Min for the sole rights to purchase gems at Mogok. This forced increasing persecution of miners, resulting in large-scale depopulation of the area by the time of the British annexation (George, 1915; Halford-Watkins, 1932). 1870A German mining engineer named Bredemeyer is put in charge of the ruby mines at Sagyin, near Mandalay (E.W. Streeter, 1892). 1878King Thebaw takes the throne upon the death of Mindon Min (Stewart, 1972). 1879Rival members of the royal family are murdered in Mandalay. Britain withdraws its resident (Stewart, 1972). 1881A party of Frenchmen under an engineer in Thebaw's employ visit Mogok (G.S. Streeter, 1889). 1882April: Burmese mission to Simla, in British India, declares to the French Consul from Calcutta that a Frenchman just obtained from King Thebaw the concession for the Burma ruby mines. This was probably just a proposal (Preschez, 1967; trans. by Olivier Galibert, June, 1994). 1883–1885French and Italian speculators negotiate with Thebaw for mining concessions at Mogok. In Feb., 1884, a French engineer, Alexandre Izambert, goes to Mandalay to solicit concession for the ruby mines of "Monieh and Rapyen." He offers Rs300,000 for the concession, which would cover 750 m on both sides of the road between Mandalay and the mines that his company proposes to build. The deal falls apart, due to a secret agreement between a Burmese minister and an Italian consular agent (Preschez, 1967; trans. by O. Galibert, June, 1994). Further massacres in Mandalay (Stewart, 1972; Keeton, 1974). 1885Britain uses the pretext of Mandalay palace massacres and a timber dispute between the Burmese government and the Bombay-Burma Trading Corp. to invade Upper Burma. The real reason was fear of French influence in an area thought vital to British interests. Mandalay is taken on Nov. 29. In December, Edwin W. Streeter becomes interested in obtaining the concession for the mines (Stewart, 1972; E.W. Streeter, 1892). 1886: Jan. 1Britain formally annexes Upper Burma. Shortly thereafter, E.W. Streeter forms a syndicate with Charles Bill and Reginald Beech. They approach the India Office to obtain the concession for the Mogok mines. Lord Dufferin puts the lease out to tender, which the Streeter syndicate wins with a bid of Rs400,000 (E.W. Streeter, 1892). 1886: Dec. 26British military force reaches Mogok area. On Jan. 27, 1887 they enter the town of Mogok. Accompanying the expedition were G.S. Streeter (E.W. Streeter's son), Col. Charles Bill, Reginald Beech and engineer Robert Gordon (G.S. Streeter, 1887a). The period between annexation and the first arrival of British troops is the golden age of local mining. For the first time in centuries, mining is free and stones can be sold without restrictions (George, 1915). 1887C. Barrington Brown is sent to Mogok by the Secretary of State for India to determine the value and conditions of the mines. His report represents the first systematic description of the deposits (Brown and Judd, 1896). 1889The Streeter syndicate joins with the Rothschilds to form the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd, which is floated on Feb. 26. Pandemonium reigns as the offer is oversubscribed fourteen times and ordinary shares rise to a 400% premium. The £1 founders' shares trade at £350 (P. Streeter, 1993). 1895Warth examines ruby mines at Naniazeik, some 80 km west of Myitkyina (Kachin State) (Penzer, 1922). 1889–1896Period of the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd first lease, with a profit shown only during 1895–1896 (Brown, 1927). 1897–1904Period of the second lease, generally profitable (except 1897–98 and 1903) (Brown, 1927). 1905–1912Period of the third lease, generally profitable (except 1909). A.H. Morgan's drainage tunnel is finished in 1908, allowing mining of once-flooded alluvials (Brown, 1927). 1913–1925Period of the supplementary agreement. Losses mount as rich areas are exhausted and the market slumps due to World War I. Profit is shown only in 1913, 1918 and 1920. Morgan's drainage tunnel is damaged in 1925 and never reopened. The company goes into voluntary liquidation on Nov. 20, 1925 (Brown, 1927). 1926–1931No buyers take the lease. The company continues small-scale mining until June 30, 1931, when the lease is surrendered (Halford-Watkins, 1932a). 1926–1947Mining is performed largely by native methods. European-style mining is limited to a few leased mines. 1938U Khin Maung Gyi (1938) reports on the Thabeitkyin stone tract west of Mogok. Sporadic mining had apparently been done for at least 50–60 years previously. 1942: 7 MayJapanese occupy Mogok. Organized mining stops until the British reoccupation (March 15, 1945), but small-scale digging continues (Ehrmann, 1957b). 1948: Jan. 5Burma achieves independence from British. 1962General Ne Win stages a military coup, plunging Burma into isolation. Thus begins one of the 20th century's cruelest and longest-running dictatorships, where Ne Win rules in a manner akin to the 19th-century Burmese kings. 1969: March 12Burmese Ministry of Mines bans exploration and mining of gems, effectively nationalizing the country's gem mines. Ruby and jade mining licenses previously issued to prospectors are revoked (Mining Journal, Annual Review, June, 1970). 1968–1980sSmuggling increases, with only a fraction of the total output ending up in government coffers. More Burmese gems are on offer in Bangkok than Rangoon. 1988Anti-government riots wrack the country. The government crushes the opposition, with thousands gunned down in Rangoon, Mandalay and other cities. 1989–94To quell mounting discontent, the military junta begins to liberalize the economy (including mining) while still maintaining total political control. The name Burma is changed to Myanmar; Rangoon is changed to Yangon.c 1990: March 9Private/government mining joint ventures are opened for tender at Mogok (Kane and Kammerling, 1992). However, smuggling remains widespread as the government's share of profits is 51.4%. 1991Rubies are found at Möng Hsu (Shan State). The Thai border town of Mae Sai becomes the main smuggling point for these gems (Hlaing, 1991). The first foreign gemologists in over 25 years visit Mogok (Ward, 1991). 1994The government reduces the export tax on gemstones to 15% (U Hla Win, pers. comm., May 2, 1994). 1995Dismayed by the continued smuggling of Möng Hsu rubies, the Burmese government closes all ruby markets at Taunggyi, moving legal trading to Rangoon (U Hla Win, pers. comm., 14 Mar., 1995). 1997–PresentGovernement policy on gemstone trading vascillates between openness and repression, with constant policy flip-flops.

|

History

The exact date when rubies were first discovered in Mogok is unknown. No doubt the first humans to settle the area found rubies and spinels in the rivers and streams. Kunz (1915) mentions a Burmese legend from the ruby mines:

According to this legend, in the first century of our era three eggs were laid by a female naga, or serpent; out of the first was born Pyusawti, a king of Pagan; out of the second came an Emperor of China, and out of the third were emitted the rubies of the Ruby Mines.

Taw Sein Ko, as told to G.F. Kunz (1915)

A similar story is related by Tin and Luce (1960):

At that time spirits carried away a certain hunter. When they reached the place where the Naga had laid her egg, the hunter finding the egg bore it away joyfully. But while he was crossing a stream, swollen by a heavy shower of rain till it overflowed its banks, he dropped it from his hand. And one golden egg broke in the land of Mogok Kyappyin and became iron and ruby in that country.

P.E.M. Tin & G.H. Luce, 1960

The Glass Palace Chronicle of the Kings of Burma

Early humans at Mogok

Vague references (Ehrmann, 1957) exist suggesting, on the basis of stone relics unearthed, that the area was first settled by Mongolians about 3000 bc. However it is likely that humans moved into the area long before that date. Halford-Watkins (1934) stated that stone, bronze and iron-age tools fashioned from a variety of jadeite have been found in alluvial diggings throughout the Mogok area.

The karst (sink-hole) topography, with its numerous underground caves, makes the Mogok area interesting for students of ancient man and prehistoric animal life. Karst topography has yielded important finds of Peking Man and younger extinct human types in China, as well as many fossil anthropoid apes. While no important archeological finds have been found at Mogok, this probably has more to do with the xenophobic attitude of the Burmese government since 1962 (and the subsequent decline in all types of academic activity), rather than a lack of study material. Interesting animal specimens did come to light before the area was closed off to outside study and it seems likely that further work will reveal further discoveries (de Terra, 1943).

Hellmut de Terra (1943) made a detailed report on the Pleistocene in the Mogok area in 1937–38 as part of a study on early man in Burma. No Pleistocene fossils were found, mainly because intensive mining had not spared even the smallest limestone fissures. However, in one cave a lower human jaw was found, believed to be that of a female human prehistoric cave-dweller dating well before the present people settled the Mogok area. Many Neolithic stone implements were also found, from the surface of old lake terraces approximately 3.2 km (2 miles) east of the town of Mogok, or from cave entrances. Certain caves were found to be inhabited by Buddhist hermits, who had installed shrines in them. One cave was even used as a cemetery. According to De Terra, "There is no question that the first people to settle in this area took refuge in the caves, because most of them face a valley that must have offered a most favorable habitat in prehistoric times. A lake, several streams and plenty of game, in addition to fertile loamy soils covering several square miles of flat ground at the valley bottom, would have offered plenty of inducement to early settlers. Here the chase could have been combined either with food-gathering or with agricultural practices."

|

The dragons of Mogok

In the vicinity of the Mogok Caves the inhabitants relate many tales of buried dragons and underground spirits, which at one time are supposed to have taken refuge underground. The association of these beasts with the cavities presumably traces back to some sort of worship, but today the people are chiefly after gem-bearing deposits: cave loam and sand. In the course of these mining operations the miners often find fossils, teeth of elephants and deer, or other bones belonging to animals now extinct. To the local people fossils are known as "nagá ajó" or dragon bones. They distinguish several types of dragons, although none of these seem to fall within the range of zoölogical nomenclature. A miner upon finding a fossil will present his find as a sort of religious offering to a near-by monastery or Buddhist shrine, and here it will be placed before an image. In some cases I learned that fossil teeth of large size, such as elephant molars, are worshipped as "Buddha's teeth," but the monks themselves do not approve of this practice…. Quite possibly the magic cult came from China where "dragon bones" continue to play an important role in native pharmacology and superstitious customs…. During my stay at Mogok, it was generally believed by the natives that I had come to search for a special kind of dragon bone. The result was that after a week's stay, prices for fossil bones soared, until an elephant's molar was valued as highly as a five-carat ruby! This attitude did not make it easy for us to acquire much of the cave fauna. At Leu Village, where I made an attempt to excavate one of the larger caves, the headman told me that years ago, near Pinpyit, miners had come across large bones. They had been so frightened at the sight of the huge animal remains that they gave up their work, closing the entrance with a stone wall so that the dragon might not walk out and ravage their village! Hellmut de Terra, 1943 |

It is unlikely that any human could live in the Mogok area for long, particularly in caves, and not discover the gems which have made the area so famous. No doubt, the first gems collected would be the well-formed red spinel crystals today termed anyan-nat-thwe (`spirit polished') by locals. Such lustrous crystals need no fashioning to display their beauty and could not help but attract attention.

Modern history of Mogok

According to G.S. Streeter (1889a), one of the sons of Kun-Lung, founder of the Shan Dynasty, is said to have governed a state in the 6th century AD, near which there were ruby mines, and to have paid an annual tribute of 2 viss (about 3.3 kgs) of rubies to the central government. However, this has not been documented. Ehrmann (1957) describes a local legend stating that modern Mogok was founded in 579 AD by headhunting tribesmen from nearby Möng Mit (Momeik). After losing their way they discovered a "mountain break full of beautiful rubies" when investigating a commotion made by many birds. This story is similar to that told of many gem deposits and is believed to derive from Sinbad the Sailor's "Valley of Precious Stones" in Sri Lanka, or perhaps al-Kazwini's relation of Alexander's valley of serpents and diamonds in India (Kunz, 1913). In the Burmese version, a fever- and serpent-ridden valley was found teeming with rubies. Far too dangerous for mere mortals to enter, the stones were obtained by casting lumps of fresh meat into the abyss. This attracted large birds of prey who snatched up the meat and brought it out, along with the rubies adhering to it. They were then retrieved from the birds' nests and droppings (see box, 'The Valley of Serpents,' Chapter 11).

Figure 6. Spoils of the jungle A variety of wild game is found in the heavy forest surrounding the Mogok ruby and sapphire mines. Here Burmese miners return from the hunt with a slain leopard. (From O'Connor, 1905)

Figure 6. Spoils of the jungle A variety of wild game is found in the heavy forest surrounding the Mogok ruby and sapphire mines. Here Burmese miners return from the hunt with a slain leopard. (From O'Connor, 1905)

The first Europeans arrive

From the earliest times of European contact with East Asia, Burma has been associated with rubies. Nicolò di Conti, the first European visitor to Ava, described the king of Ava thus:

The King rideth upon a white Elephant, which hath a chayne of golde about his necke, being long unto his féete, set full of many precious stones.

Nicolò de' Conti, 1419–1444

from Frampton's Elizabethan translation (Penzer, 1929)

Ludovico di Varthema visited Pegu between 1502 and 1508:

The sole merchandise of these people is jewels, that is, rubies, which come from another city called Capellan [Ruby Mines District in Burma], which is distant from this thirty days' journey; not that I have seen it, but by what I have heard from merchants…. Do not imagine that the King of Pego enjoys as great a reputation as the King of Calicut, although he is so humane and domestic that an infant might speak to him, and he wears more rubies on him than the value a very large city, and he wears them on all his toes. And on his legs he wears certain great rings of gold, all full of the most beautiful rubies; also his arms and his fingers all full. His ears hand down half a palm, through the great weight of the many jewels he wears there, so that seeing the person of the king by a light at night, he shines so much that he appears to be a sun.

Ludovico di Varthema of Bologna (Temple, 1928)

Di Varthema and his party offered the king coral as a gift. This act of generosity so impressed the king that he gave them over 200 rubies (Temple, 1928).

Duarte Barbosa, visiting Burma about the same time, gave one of the best accounts of rubies:

Capelam

And yet further inland beyond this city [Ava] and Kingdom there is another Heathen city whith its own King, who nevertheless is subject and under the lordship of Ava; which city or Kingdom they call Capelam. Around it are found many rubies which are brought in for sale to the Ava market, and are much finer than those of that place.

Of Rubies

In the first place rubies are produced in the Land of India and are found chiefly on a river called Pegu. These are the best and finest, and are called Numpuclo* by the Malabares, and when they are clean and without flaw they fetch a good price. To test their quality the Indians put them on the tongue; those which are finest and hardest are held to be the best. To test their transparency they fix them with wax on a very sharp point and looking towards the sun they can find any blemish however slight. They are also found in certain deep pits in the mountains beyond the said river.

In Pegu they know how to clean but not how to polish them, and they therefore convey them to other countries, especially to Paleacate, Narsinga, Calicut and the whole of Malabar, where there are excellent craftsmen who cut and mount them.

Dames' annotations

* Pegu Rubies. The name Numpuclo here stated to be used for the Pegu rubies in Malabar is explained by Mgr. Dalgado in his Glossario. He considers that the initial letter is wrongly given owing to a copyist's mistake, and that the word should be read chumpuclo, as in Malayalam the name of the ruby is chuvappukallu from kallu "stone" and chuvappu "ruby," literally "ruby-stone." For the places where these rubies are found see p. 107 and p. 108.

Duarte Barbosa, ca. 1500–1517 (from Dames, 1858)

Figure 7. A stunning 1734-ct Mogok ruby crystal sits atop the marble which nurtured it into existence. (Photo: Thomas Frieden).The first Englishman to visit Burma was Ralph Fitch, in 1586, whose journey led to the founding of the British East India Company. He said:

Figure 7. A stunning 1734-ct Mogok ruby crystal sits atop the marble which nurtured it into existence. (Photo: Thomas Frieden).The first Englishman to visit Burma was Ralph Fitch, in 1586, whose journey led to the founding of the British East India Company. He said:

Caplan is the place where they finde the rubies, saphires, and spinelles: it standeth sixe dayes journey from Ava in the Kingdome of Pegu. There are many great high hilles out of which they digge them. None may go to the pits but onely those which digge them.

Ralph Fitch, 1586 (in Hakluyt, 1903–05)

Not only did Fitch comment upon the rubies, but also told of a curious local custom mentioned by many of the early European travelers to the area:

In Pegu, and in all the countreys of Ava, Langeiannes, Siam, and the Bramas, the men weare bunches or little round balles in their privy members: some of them weare two and some three. They cut the skin and so put them in, one into one side and another into the other side; which they do when they be 25 or 30 years old, and at their pleasure they take one or more of them out as they thinke good… The bunches aforesayd be of divers sorts: the least be as big as a litle walnut, and very round: the greatest are as big as a litle hennes egge: some are of brasse and some of silver: but those of silver be for the king and his noble men. They were invented because they should not abuse the male sexe for in times past all those countries were so given to that villany, that they were very scarse of people.

Ralph Fitch, 1586 (in Hakluyt, 1903–05)

Just how such balls would prevent masturbation or homosexuality is unclear. But the custom continues into the present day. During one 1980s visit to Burma, William Spengler met a man who claimed that he had pearls implanted in his genitals, to heighten sexual pleasure (very pers. comm., 20 March, 1995).

Alexander Hamilton (1744), who traveled to India and Burma in the 18th century, also had some interesting remarks about the Burmese. In reference to the sarongs worn by ladies, he said:

Under the Frock they have a Scarf or `Lungee' doubled fourfold, made fast about their Middle, which reaches almost to the Ancle, so contrived, that at every Step they make, as they walk, it opens before, and shews the right Leg and Part of the Thigh.

This Fashion of Petticoats, they say, is very ancient, and was first contrived by a certain Queen of that Country, who was grieved to see the Men so much addicted to `Sodomy,' that they neglected the pretty Ladies. She thought that by the Sight of a pretty Leg and plump Thigh, the Men might be allured from that abominable Custom, and place their Affections on proper Objects, and according to the ingeiuous Queen's Conjecture, that Dress of the `Lungee' had its desired End, and now the Name of Sodomy is hardly known in that Country.

Alexander Hamilton, 1744

Hamilton also mentioned the products of Burma:

The Product of the Country is Timber for building, Elephants, Elephants Teeth, Bees-wax, Stick-lack, Iron, Tin, Oyl of the Earth, Wood-oyl, Rubies the best in the World, Diamonds, but they are small, and are only found in the Craws of Poultry and Pheasants, and one Family has only the Indulgence to sell them, and none dare open the Ground to dig for them… About twenty Sail of Ships find their Account in Trade for the limited Commodities, but the Armenians have got the Monopoly of the rubies, which turns to a good Account in their Trade; and I have seen some blue Sapphires there, that I was told were found on some Mountains of this Country.

Alexander Hamilton, 1744

|

Figure 8. One of the earliest European maps to show the position of the ruby mines, based on information provided by a Burmese slave to Francis Hamilton in 1824. Roman numerals indicate the average number of stages (walking days) between points. Although the distances are relatively accurate, Mogok (`Mogouk') actually lies further east from Amarapura (near present-day Mandalay). (Redrawn by the author from Hamilton, 1824) |

Figure 9. Native gem diggers at Mogok about the turn of the century. (From O'Connor, 19Such tales certainly contributed to the European view of the Orient as a place of wonder and exotic mystery. But these were nothing compared to that related by the famous French traveler and diamond merchant, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, about the King of Bhutan:

Figure 9. Native gem diggers at Mogok about the turn of the century. (From O'Connor, 19Such tales certainly contributed to the European view of the Orient as a place of wonder and exotic mystery. But these were nothing compared to that related by the famous French traveler and diamond merchant, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, about the King of Bhutan:

There is no King in the World more fear'd and more respected by his Subjects then the King of Boutan; being in a manner ador'd by them…. One thing they told me for truth, that when the King has done the deeds of nature, they diligently preserve the ordure, dry it and powder it, like sneezing-powder: and then putting it into Boxes, they go every Market-day, and present it to the chief Merchants, and rich Farmers, who recompence them for their kindness: that those people also carry it home, as a great rarity, and when they feast their Friends, strew it upon their meat. Two Boutan Merchants shew'd me their Boxes, and the Powder that was in them.

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, 1677–8

That is one banquet in which this beggar would decline to partake. Down Satan! But it is interesting that the passage was apparently so shocking to Victorian British that it was removed from the later editions edited by Valentine Ball.

|

Men of the cloth  Figure 10. Traders offer jadeite, sapphires and rubies in Rangoon's Shwebontha Street gem market. (Photo by the author, 1992) Figure 10. Traders offer jadeite, sapphires and rubies in Rangoon's Shwebontha Street gem market. (Photo by the author, 1992)

Cæsar Fredericke of Venice, who journeyed to Asia in 1563, gave one of the earliest accounts of the fascinating Asian technique of negotiating prices in secret by covering the hands of the buyer and seller with a cloth. There are many Marchants that stand by at the making of the bargaine, and because they shall not understand howe the Jewels be solde, the Broker and the Marchants have their hands under a cloth, and by touching of fingers and nipping the joynts they know what is done, what is bidden, and what is asked. So that the standers by knowe not what is demaunded for them, although it be for a thousand or 10. thousand duckets. For every joynt and every finger hath its signification. For if the Marchants that stande by should understand the bargaine, it would breede great controversie amongst them. Cæsar Fredericke, 1563, (in Hakluyt, 1903–05) |

Of the many accounts of the gems of Pegu, as Burma was then known, perhaps most interesting was that of Cæsar Fredericke of Venice, who journeyed to Asia in 1563. The following is his description of the gem trade in Pegu.

…it is a thing to bee noted in the buying of jewels in Pegu, that he that hath no knowledge shall have as good jewels, and as good cheap, as he that hath practized there a long time. There are in Pegu foure men of good reputation, which are called Tareghe, or brokers of Jewels… through the hands of these foure men passe all the Rubies: for they have such quantitie, that they knowe not what to doe with them, but sell them at most vile and base prices. When the Marchant hath broken his mind to one of these brokers or Tareghe, they cary him home to one of their Shops, although he hath no knowledge in Jewels: and when the Jewellers perceive that hee will employ a good round summe, they will make a bargaine, and if not, they let him alone… when any Marchant hath bought any great quantitie of Rubies, and hath agreed for them, hee carieth them home to his house, let them be of what value they will, he shall have space to looke on them and peruse them two or three dayes: and if he hath no knowledge in them, he shall alwayes have many Marchants in that Citie that have very good knowledge in Jewels; with whom he may alwayes conferre and take counsell, and may shew them unto whom he will; and if he finde that hee hath not employed his money well, hee may returne his Jewels backe to them who hee had them of, without any losse at all. Which thing is such a shame to the Tareghe to have his Jewels returne, that he had rather beare a blow on the face then that it should be thought that he solde them so deere to have them returned.

Cæsar Fredericke, 1563 (in Hakluyt, 1903–05)

Thus "spake" Cæsar Fredericke. After reading his tale, one can only wish and sigh that modern-day gem merchants would be so understanding. Perhaps businessmen haven't really changed all that much. Fredericke was no doubt just an example of a species still in flourish. Had he made his journey in the present day, Fredericke may have returned to Europe with wooden elephants – in addition to his gem purchases.

|

Guiseppe d'Amato's description of Mogok From 1597 AD onwards, Mogok was part of Burma proper. The first European to actually visit the mines in the Mogok area and write about them was a Portuguese priest, Giuseppe d'Amato, sometime before 1833. D'Amato arrived in Burma sometime in 1784, and spent the rest of his life there. He resided at Moun-lha (Mon-lhá), some 30 miles (48 km) northwest of Ava, where he died in 1832 (Burney, 1832). His brief account of the ruby workings at Kyatpyin was published posthumously in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal and is reproduced in its entirety below: IV.--Short Description of the Mines of Precious Stones, in the District of Kyat-pyen, in the Kingdom of Ava.[Translated from the original of Père Giuseppe d'Amato] The territory of Kyat-pyen * (written Chia-ppièn by d'Amato) is situated to the east, and a little to the south of the town of Mon-lhá , distant 30 or 40 Burman leagues, each league being 1000 taa**, of seven cubits the taa |; say 70 miles [113 km]. It is surrounded by nine mountains. The soil is uneven and full of marshes, which form seventeen small lakes, each having a particular name. It is this soil which is so rich in mineral treasures. It should be noticed, however, that the ground which remains dry is that alone which is mined, or perforated with the wells whence the precious stones are extracted. The mineral district is divided into 50 or 60 parts, which, beside the general name of "mine," have each a different appellation. The miners, who work at the spot, dig square wells, to the depth of 15 or 20 cubits, and to prevent the wells from falling in, they prop them with perpendicular piles, four or three on each side of the square, according to the dimensions of the shaft, supported by cross pieces between the opposite piles. When the whole is secure, the miner descends, and with his hands extracts the loose soil, digging in a horizontal direction. The gravelly ore is brought to the surface in a ratan basket raised by a cord, as water from a well. From this mass all the precious stones and any other minerals possessing value are picked out, and washed in the brooks descending from the neighbouring hills. Besides the regular duty which the miners pay to the Prince, in kind, they are obliged to give up to him gratuitously all jewels of more than a certain size or of extraordinary value. Of this sort was the tornallina (tourmaline?) presented by the Burman monarch to Colonel Symes. It was originally purchased clandestinely by the Chinese on the spot; the Burmese court, being apprized of the circumstance, instituted a strict search for the jewel, and the sellers, to hush up the affair, were obliged to buy it back at double price, and present it to the king. You*** may ask me, to what distance the miners carry their excavations? I reply, that ordinarily they continue perforating laterally, until the workmen from different mines meet one another. I asked the man who gave me this information, whether this did not endanger the falling in of the vaults, and consequent destruction of the workmen? but he replied, that there were very few instances of such accidents. Sometimes the miners are forced to abandon a level before working to day-light, by the oozing in of water, which floods the lower parts of the works. The precious stones found in the mines of Kyat-pyen , generally speaking, are rubies, sapphires, topazes, and other crystals of the same family, (the precious corundum .) Emeralds are very rare, and of an inferior sort and value. They sometimes find, I am told, a species of diamond, but of bad quality****. The Chinese and Tartar merchants come yearly to Kyat-pyen , to purchase precious stones and other minerals. They generally barter for them carpets, coloured cloths, cloves, nutmegs and other drugs. The natives of the country also pay yearly visits to the royal city of Ava, to sell the rough stones. I have avoided repeating any of the fabulous stories told by the Burmans of the origin of the jewels of Kyat-pyen . There is another locality, a little to the north of this place, called Mookop , in which also abundant mines of the same precious gems occur. Note .--While I am writing this brief notice, an anecdote is related to me by a person of the highest credit, regarding the discovery of two stones, or, to express myself better, of two masses ( amas ) of rubies of an extraordinary size, at Kyat-pyen . One weighed 80 biches*****, Burmese weight, equivalent to more than 80 lbs.! the second was of the same size as that given to Colonel Symes. When the people were about to convey them to the capital to present them to the king, a party of bandits attacked Kyat-pyen for the second time, and set the whole town on fire. Of the two jewels, the brigands only succeeded in carrying off the smaller one; but the larger one was injured by the flames: the centre of the stone, still in good order, was brought to the king. I learned this from a Christian soldier of my village of Mon-lhá , who was on guard at the palace when the bearer of the gem arrived there. Prinsep's annotations* The Kyat-pyen mountains are doubtless the Capelan mountains mentioned as the locality of the ruby, in Phillips' Mineralogy--"60 miles from Pegue, a city in Ceylon ." Though it might well have puzzled a geographer to identify them without the clue of their mineral riches. ** Estimating the cubit at 1 1 / 2 feet, the league will be 10,500 feet, or nearly two miles;--about an Indian kos . [The cubit is an ancient measure of length based on the forearm] *** The letter seems to have been intended for some scientific friend in Italy. **** Probably the turmali or transparent zircon, which is sold as an inferior diamond in Ceylon. [Vide vol. i. page 357.] ***** The Père d'Amato's biche is the bisse of Mendez Pinto, and the old travellers, and the biswa or vis of Natives of India. The Burmese word is Peik-tha , which is equivalent to 3 1 / 2 lbs., and to a weight on the Coast of Coromandel called vis . B. Père Giuseppe d'Amato, 1833 (with notes from James Prinsep) |

Ralph Fitch also mentioned the Tareghe, and said that if they failed to pay a merchant in a timely fashion, the merchant could "take [the Tareghe's] wife and children and his slaves, and binde them at your doore, and set them in the Sunne; for that is the law of the countrey." (Hakluyt, 1907) A noble custom, and perhaps one which could be applied today to politicians, tax collectors and sundry dictators.

In the year 1597 AD, the Burmese King Nuha-Thura Maha Dhama-Yaza ratified a royal edict exchanging small parts of Burma under his control for the Mogok Stone Tract, previously under the control of a Shan saopha (Burmese = sawbwa; or prince). Both the Burmese text of this order and an English translation are reproduced in Figure 11 (George, 1915).

According to Halford-Watkins (1934), the town of Mogok did not exist at that date, the name merely being applied to a mining area and series of paddy fields situated some five miles (8 km) from Thapanbin village. Due to the difficult nature of the country, the journey between the two places could not be completed before nightfall, which is mochok in Burmese. Thus the name Mochok (`nightfall camping ground'), which was later corrupted to Mogok. Another possible derivation of the name is that it is the place where the mountains meet the sky, in allusion to the mountain tops being hidden in the clouds during the rainy season.

One might wonder why the Shan saopha would agree to such a one-sided deal, where a relatively worthless piece of land was traded for the world's greatest ruby mines. It is indeed strange what people will do with a knife at their throat.

Figure 12. "An' I seed her first a-smokin' of a whackin' white cheroot…" (Rudyard Kipling, Mandalay ) (Photo: Thomas Frieden)

Figure 12. "An' I seed her first a-smokin' of a whackin' white cheroot…" (Rudyard Kipling, Mandalay ) (Photo: Thomas Frieden)

Burmese monarchs worked the Stone Tract as a royal monopoly, in a thoroughly despotic manner. All rubies above the value of Rs2000 were considered Crown property and failure to surrender them was punishable by torture and death. Father Sangermano, an Italian priest who lived in Ava between 1783 and 1806, discussed this:

With regard to precious stones, a few inferior sapphires and topazes are sometimes found; but it is the rubies of the Burmese Empire which are its greatest boast, as both in brilliancy and clearness they are the best in the world. The mines that contain them are situated between the countries of Palaon and the Koè. The Emperor employs inspectors and guards to watch these mines, and appropriates to himself all the stones above a certain weight and size; the penalty of death is denounced against any one who shall conceal, or sell, or buy any of these reserved jewels.

Father Sangermano, 1893

The Burmese Empire a Hundred Years Ago

But conceal them they did. The story of the Nga Mauk Ruby provides an example. Nga Mauk, a poor miner, uncovered a large fine ruby which was later divided into two excellent pieces along an incipient flaw. One half was given to the king, but the other secretly sold. The king learned of the deception when he proudly showed his half to the dealer who had bought the other part (Keely, 1982). Enraged, he sent his minions to exact punishment. All area villagers were placed into a makeshift stable and burned alive. Even today, some 150 years later, the remains of this horrible cremation can be seen at a spot called Laung Zin, which means "fiery platform."1 Daw Nann, his wife, is said to have watched his blazing death from a hill near Kyatpyin which is today called Daw Nann Kyi Taung (`the hill from where Daw Nann looked down'). As for the famous Nga Mauk ruby, it disappeared from the palace the night the British conquered Ava in 1885 (Keely, 1982; E.W. Streeter, 1892; Clark, 1991). 2

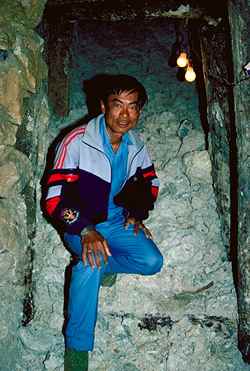

Figure 13. A native miner at a twin-lon mine, near Mogok, Burma. (From O'Connor, 1905)

Figure 13. A native miner at a twin-lon mine, near Mogok, Burma. (From O'Connor, 1905)

In wars with the neighboring kingdoms of Manipur and Assam, prisoners were taken. During the latter part of the 19th century, production from Mogok declined drastically due to the despotic rule and heavy handed policies of the Burmese monarchs' agents. In their quest to extract as much tax as possible, they effectively drove people from the area.

Empire building

On the road to Mandalay, where the old Flotilla lay,

With our sick beneath the awnings when we went to Mandalay!

Oh the road to Mandalay, where the flyin'-fishes play,

An' the dawn comes up like thunder outer China 'crost the Bay!

Rudyard Kipling, 1892, Mandalay

The British move into Burma came slowly, but inevitably. Disputes on the border with British India led to the first Anglo-Burmese war in 1824–6. As a result, Arakan, Assam and Tenasserim were ceded to the East India Company. Pegu was annexed after the British won the second Anglo-Burmese war of 1852–3. In 1885, commercial disputes and reported corruption and massacres at the Court gave the British the needed excuse to annex all of Upper Burma, including the Mogok Stone Tract.

Mandalay was taken on Nov. 29, 1885. While the British expedition quickly took the capital, it was over one year before Mogok was occupied and five long years of skirmishes before the rest of Upper Burma was secured.

Unfortunately, the fabulous jewels of King Thebaw were never recovered. When the British took Mandalay, they sealed the palace, but Thebaw's ministers requested permission for Queen Supayalat's ladies to come and go as they wished. General Prendergast, leader of the British expedition, agreed over the objections of G.S. White. White wrote: "Colonel Sladen… sent me word that the ladies might be allowed to come and go freely. I entered a protest that everything of small size and great value would be passed out by the ladies…. [as a result] thousands of pounds of booty were, I am sure, lost to the army." (Stewart, 1972)

Figure 14. King Thebaw and Queen Supayalat, the last monarchs of Burma. (From the Illustrated London News, 16 Jan., 1886)

Figure 14. King Thebaw and Queen Supayalat, the last monarchs of Burma. (From the Illustrated London News, 16 Jan., 1886)

Halford-Watkins (1934) felt the magnitude of the royal treasure was highly exaggerated, pointing out that there is not a single written first-hand description of these gems:

…[the monarchs'] persons were regarded as being so very sacred that such regalia had to be viewed from a very respectful distance, so that it was quite impossible for anyone even to judge of the genuine nature of the stones, much less to estimate their value. [I have] talked with several of the old officials and habitués of the palace of the times of both King Mindoon Min and Thebaw, and has been assured that the majority of these tales are pure invention, and that most of the stones worn were of quite ordinary quality, and sometimes very poor, quality; while many of the large gems attached to the robes and other regal paraphernalia were merely coloured glass.

This rather calls to mind the stories of the valuable ruby trousers buttons worn by my friend the Sawbwa of Momeit during his visit to London, which were made so much of at the time by a certain section of the press. The Sawbwa invariably wears his native costume, in which his trousers do not possess a single button of any kind, much less ruby ones.

The fact that only a comparatively few gems of any importance were found in the possession of King Thebaw at the taking of Mandalay confirms the statements made by these old officials. And it is a known fact that when Queen Supayalat left she carried with her all her personal gems wrapped in a handkerchief which was so small that she dropped it as she was boarding the steamer, and did not miss it until it was returned by a soldier who had picked it up. Of course it was said that the majority of the treasure had been buried as the British advanced, and there has since been much excavating and searching done in and around the square mile of Fort Dufferin, in some of which [I have] taken an active part. But so far the result has been a total blank, as the old officials always said that it would be, owing to nothing having been buried, and but comparatively little stolen, for the simple reason that it was not there to be made away with.

J.F. Halford-Watkins, 1934

Figure 15. British camp at Mogok. (From the Illustrated London News, 19 Feb, 1887)

Figure 15. British camp at Mogok. (From the Illustrated London News, 19 Feb, 1887)

Shortly after the annexation of Upper Burma in December, 1885, London jeweler, Edwin Streeter, was breakfasting in Paris and happened to overhear two men discussing the Burma ruby mines. After introducing himself, he found that a French firm, Bouveillein & Co., had arranged a provisional lease of the ruby mines from King Thebaw. With the British annexation, this lease was then worthless.

Upon his return to London, Streeter contacted the India Office with the prospect of obtaining the lease. A syndicate was formed, consisting of Streeter, Charles Bill, Reginald Beech and Streeter's son, George Skelton Streeter. Captain Aubrey Patton was selected to travel to Rangoon for negotiations. He departed from London in January, 1886. On Patton's arrival in Burma, it was found that Gillanders, Arbuthnot & Co. of Calcutta and Rangoon, in conjunction with an unknown London jewel broker, had already offered two lakhs 3 of rupees for the lease. The Streeter syndicate countered with an offer of three lakhs, which Gillanders, Arbuthnot & Co met. The government then decided to offer the lease for public tender. In respect of the further competition, Streeter increased the offer to four lakhs (£30,000) for a five-year lease, which was provisionally accepted, pending investigation into native mining rights (E.W. Streeter, 1892; Times of London, Aug. 17, 1887). Meanwhile, as per the British Indian government's suggestion, Streeter dispatched his son, along with Bill, Beech and Rangoon engineer, Robert Gordon, to accompany the British military expedition to Mogok, which left Mandalay in November, 1886 (E.W. Streeter, 1892).

Figure 16. Geological map of the Mogok Stone Tract in Upper Burma. Most gems are recovered from alluvial deposits situated near the towns of Mogok and Kathé. (Modified from Iyer, 1953)

Figure 16. Geological map of the Mogok Stone Tract in Upper Burma. Most gems are recovered from alluvial deposits situated near the towns of Mogok and Kathé. (Modified from Iyer, 1953)

Mogok was occupied by British troops in December, 1886. In February, 1887, Mr. F. Atlay arrived at the mines to act as agent for the Streeter syndicate. He subsequently became mine manager, a position he continued to hold under the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd.

It was not until 1889 that the lease actually began. The reasons for the delay were entirely political. Edward Moylan, a disbarred barrister, managed to convince many in London that the lease holder, E.W. Streeter, had acquired it through dishonest means (such as bribery). Moylan, who was then Burma correspondent for the Times of London, succeeded in raising enough questions to cause the lease to be reexamined. In the end, his true motive was revealed; he was working for Gillanders, Arbuthnot & Co, who hoped to win the lease themselves 4 (Stewart, 1972).

At this point, enter one Moritz Unger, a Paris jeweler. He claimed to represent a powerful European syndicate with the London Rothschilds at the head, and in March, 1886, applied for the lease. Unfortunately, he could produce no evidence of this syndicate's existence, and soon disappeared from the scene (London Times, Aug. 17, 1887).

In light of the controversy surrounding the lease, the British government decided to send a trained geologist to report on the mines. C. Barrington Brown reached Mogok on January 10, 1888. His was the first detailed geologic study of the Mogok area (Brown & Judd, 1896). Brown's report was eventually received by the Secretary of State and the lease was put up for renewed tender (E.W. Streeter, 1892).

By this time, the London Rothschilds were involved. N.M. Rothschild and Sons, through their Exploration Co subsidiary, had written to the Secretary for India, asking if they could bid for the mines. Eventually the Streeter syndicate joined with N.M. Rothschild and the Exploration Co., and together they floated the Burma Ruby Mines, Ltd. A fresh offer was tendered and was accepted on Nov. 27, 1888. The lease was signed on February 22, 1889, giving the company seven years, with a renewal option, at an annual rent of Rs400,000, plus one sixth of net profits (E.W. Streeter, 1892; P. Streeter, 1993). Streeter and his associates later sold the lease to the Burma Ruby Mines, Limited for £55,000 (Brown, 1927).

Notes

- George (1915) has reported that the name Kyatpyin, from which the Capelan of early European travellers is derived, comes from the fact that the people slept on platforms, with fires underneath to keep them warm at night. [ return to chapter text ]

- For a slightly different version of this story, see Chapter 10. [ return to chapter text ]

- One lakh equals 100,000 rupees. [ return to chapter text ]

- A Mr. Danson was reportedly sent to Mogok at one stage to report on the mines for Gillanders, Arbuthnot & Co. (George, 1915). [ return to chapter text ]