The examination of a yellow sapphire provides a lesson in the power of gemological microscopy.

Yellow Sapphire ID • Passport to Obscurity

Obscurity is a lonely place, right next door to oblivion.

While a passport typically conjures up images of freedom, the open road and travel to exotic locales, not every destination is five-star. This point was driven home during the examination of a group of yellow sapphires recently sent to the laboratory for identification.

The lot consisted of several yellow sapphires of graduated weight, each with similar shape, facet arrangement and face-up color. It appeared likely that all were intended for a single piece of jewelry.

In gems of this type, inclusions are often sufficient to immediately identify the host as a natural sapphire, as well as prove or disprove heat treatment. When present, a 3160 infrared peak is also important evidence of natural, untreated origin in yellow sapphires. With but one exception, all the sapphires in the group contained obvious visual micro-evidence of natural origin, along with moderate to strong 3160 peaks in the infrared, both tickets to paradise.

One sapphire, however, showed no obvious inclusions and no telltale 3160 peak, immediately raising an alarm. This meant it would require additional examination consisting of a detailed microscopic inspection using a combination of fiber-optic and darkfield illumination, with polarized light, if needed. Careful scrutiny would be necessary if a decision was to be reached as to the full identity.

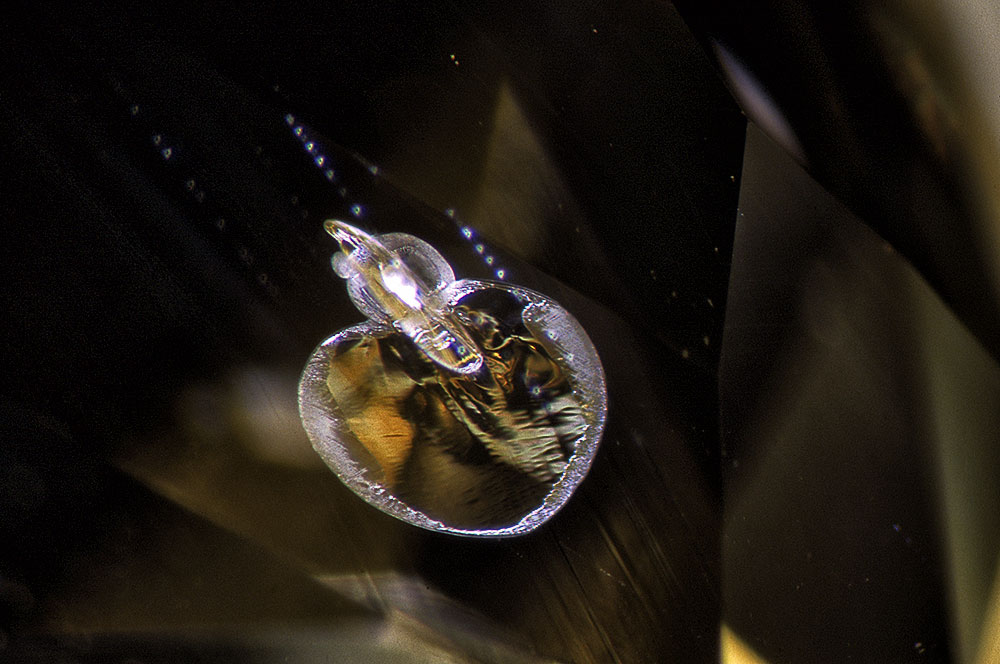

Microscopic search parties were sent out throughout the gemstone on a facet-to-facet search. All reported back empty-handed. Except one. As the piece was rocked to-and-fro, a weak flash of light winked from the abyss. Zooming in revealed a miniscule, inconspicuous heat-damaged inclusion with an associated mirror-reflective discoid decrepitation halo (Figure 1). While at just 0.01 mm in diameter (as measured with an eyepiece micrometer), this inclusion was certainly tiny; but it was all that was needed to both eliminate the possibility of synthetic origin and prove heat treatment.

Figure 1. Destination unknown…

Although relatively small and inconspicuous at roughly 0.01 mm diameter, this heat-treatment damaged crystal with its diagnostic discoid decrepitation halo (also produced by heat treatment) is all the proof needed to destroy the natural reputation of its host yellow sapphire. Photomicrograph: © John I. Koivula/microWorld of Gems

Separate identification reports were requested for every gemstone and all except one received natural, unheated reports. While we do not know the fate of this individual, we suspect that when the client studied the reports, the guilty gemstone was pulled and a natural replacement found. The treated gemstone is probably now destined for a lesser piece of jewelry, or perhaps it will simply be placed somewhere in a drawer, cast aside and forgotten.

Inclusions are passports, identification papers. From the transparent calcite rhombs in Burma rubies to the rutile arrows in Sri Lankan sapphires, these tiny disturbances so often provide entreé to a better place. But as this tale tells, inclusions may also be tickets to a less-than distinguished future.

When inclusions provide proof of natural origin, they allow entry to paradise. But when the reverse is true, when they prove a gem to be treated or synthetic, they can be passports to obscurity. And obscurity is but a short walk from the abyss of oblivion.

Notes

First published in 2005.

About the authors

John Koivula is the author of the magnificent Photoatlas of Inclusions in Gemstones, Vols. 1–3, along with several other books and over 800 articles. He is currently Chief Research Gemologist at the Gemological Institute of America and is the world's foremost gem photomicrographer. John was also the scientific advisor to the famous MacGyver television series. Many of his books and enlargements of his images are available through microWorldofGems.com.

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard's Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology.