A description of the fracture healing of Mong Hsu ruby, along with the problems this has created in the gem trade.

Foreign Affairs • The Fracture Healing/Filling of Mong Hsu Ruby

PICTURE THIS: a well-known European dealer sells a 2.5-carat Möng Hsu ruby to a major jeweler in Europe. This jeweler then sells the stone to a Japanese client through their Japanese subsidiary. The client now takes the stone to a gemological lab, which issues a report stating that the gem's fractures have been healed with a foreign substance. Now the fun really starts. Feeling cheated, the customer returns the stone and demands a full refund. Thus begins a lawsuit which involves several firms, spans two continents and is still snaking its way through the court system in France.

Figure 1 Untreated rough Möng Hsu ruby on offer in Thailand's Mae Sai market; April 1996. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

Figure 1 Untreated rough Möng Hsu ruby on offer in Thailand's Mae Sai market; April 1996. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

Today, courts are increasingly being called upon to arbitrate such disputes, largely because sellers have failed to disclose the flux healing of fractures in Möng Hsu ruby from Burma. The problem is a huge one, a corundum conundrum that will only escalate until the trade begins to enforce a policy of full disclosure of all gemstone enhancements. The following article examines the roots of the issue.

Möng Hsu is not Mogok

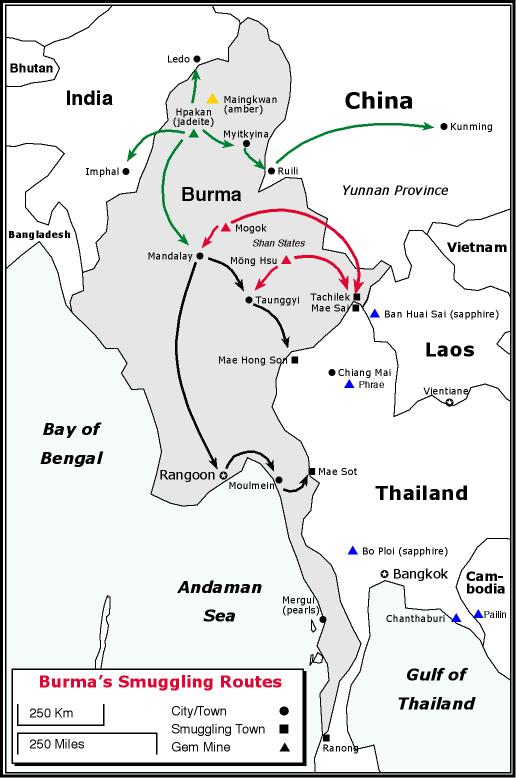

Mogok is not the only active ruby mining area in Burma. Stones from the Möng Hsu (pronounced 'Maing Shu' by the Shan; 'Mong Shu' by the Burmese) deposit, located in Myanmar's Shan State, northeast of Taunggyi, first began appearing in Bangkok in mid-1992. Since that time they have completely dominated the world's ruby trade in sizes of less than 3 ct. Indeed, 99% of all the rubies traded today in Chanthaburi (Thailand) are from Möng Hsu.

terms of quality, Möng Hsu rubies cannot compete with Mogok stones. Before heat treatment, the Möng Hsu ruby is certainly an ugly duckling. There aretwo major problems. The first is dense silk clouds and a strong purplish color, making most stones look like low-grade, cloudy rhodolite garnet. This is mainly due to the crystal's unusual blue cores. Ordinary heat-treatment removes the blue, as well as removing silk, making the final product a rich, clear red. The market generally accepts such heated stones without a quibble.

This is not the case for the second problem. Most Möng Hsu stones are heavily fractured and Thai burners have combated the cracking by healing the cracks with a flux such as borax. Heating the stones with borax and other chemicals actually melts their surfaces, including the surfaces of cracks. The corundum within this molten material then redeposits on the fracture surfaces, filling and healing the fractures shut. Undigested material cools into pockets of flux glass. Essentially this amounts to a microscopic deposition of synthetic ruby to heal the cracks closed.

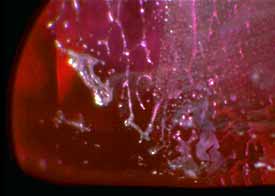

Figure 2 Similar to Figure 3, in transmitted light the two-phase flux glass filling is clearly seen. Transmitted light; 100x. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

Figure 2 Similar to Figure 3, in transmitted light the two-phase flux glass filling is clearly seen. Transmitted light; 100x. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

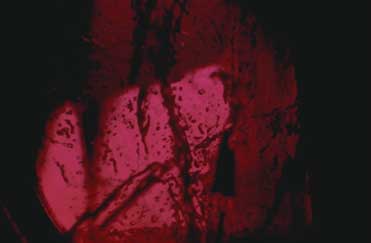

Figure 3 The whitish, flux remnants in this healed fracture are clearly visible. Reflected light; 100x. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

Figure 3 The whitish, flux remnants in this healed fracture are clearly visible. Reflected light; 100x. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

In the broadest sense, this is akin to the oiling of emerald – both treatments involve reduction of reflections from included cracks/fissures. Similar to placing an ice cube in water, a filled fracture is much less visible because the filler replaces air (RI = 1.00) with a substance which has an RI that more closely matches the gem itself (1.76–1.77). However, the flux healing of Möng Hsu rubies differs in three important respects:

- The Möng Hsu ruby treatment is permanent and irreversible – unlike the oil in an oiled emerald, the remnant pockets of flux will not drain out in the future, nor can they be removed.

- The Möng Hsu ruby treatment actually improves a stone's durability, since the fractures are healed shut.

- The Möng Hsu ruby treatment does not really involve a fracture filling, but more a healing of the fractures and fissures, with any filling merely a remnant of the process. In many respects, it is a welding of fractures, similar to the joining of two pieces of metal with heat and a flux to dissolve them at a temperature below their melting point.

Hence we have a superior treatment for Möng Hsu ruby, one which is actually more stable than ordinary oiling. So what is all the fuss about? First, purchasers of ruby are not accustomed to buying heavily-fractured stones. Unlike emerald, clean rubies do exist. Second, the process can also be accomplished with heat alone. If such stones are deemed acceptable without further comment, what happens when only heat is used? What is important here is not the how, but the fact that these stones once had open fractures that are no longer there.

Figure 4

Diagram showing the mechanism of flux healing of a fracture in corundum.

A. Open fracture/fissure, unhealed

B. During heat treatment, flux enters the fracture and dissolves the walls of the crack.

C. During cooling, molten corundum recrystallizes in the crack, thus healing it closed. The newly-crystallized ruby is essentially a synthetic ruby grown in the crack alone. It contains small pockets of now-solidified flux glass, along with some trapped gas pockets. For purposes of this diagram, the surrounding natural ruby and the synthetic ruby in the crack are shown in two different colors. In reality, no distinction can be seen between the surrounding ruby and the newly grown synthetic ruby.

D. Any flux glass present on the surface can be dissolved away with acid. The synthetic ruby in the crack is unaffected by the acid, as is the ruby as a whole.

(Illustration: R.W. Hughes; modified from Hänni, 2001, SSEF)

|

Möng Hsu ruby trading While the Burmese government has taken steps to control the trade in Möng Hsu ruby, much of it makes its way straight to the northern Thai border town of Mae Sai.

Figure 4 In transmitted light the flux glass filling often appears two-phase. Transmitted light; 100x. (Photo: R.W. Hughes) The Mae Sai ruby market is located in Soi Taub Tim ('Ruby Lane'), which is next to the Mae Sai Hotel. On the day one of the authors (RWH) visited in April of 1996, there were probably upwards of 500 people engaged in selling rough ruby from Möng Hsu. A few cut stones were on offer, but most of the material was rough. Perhaps 50 kg of rough was on display in the market; no doubt much more was being held behind closed doors. In late June of 1997, during another visit, the market was only a fraction of that size, with just a few sellers and just a few kilos of rough on display.

Figure 5 Rough Möng Hsu ruby before (left) and after (right) heat treatment in the Mae Sai market; June 1997. (Photo: R.W. Hughes) |

Tale of the tape. According to Bangkok dealer, Mark Smith (pers. comm., June 1996), most cut Möng Hsu ruby is sub-0.50 ct. In the 1–1.5 ct range, plenty of near-opaque material is available for $20–100. Smith stated that, based on his experience, 80–90% of all production in the 1.0–1.5 ct size is under $400/ct. Better qualities are also available, but less common. Clean stones of 1.0–1.5 ct fetch up to $1500/ct.

Figure 6 Mae Sai burner, Somkual Plylaharn, opens his oven after burning Möng Hsu rubies; June 1997. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

Figure 6 Mae Sai burner, Somkual Plylaharn, opens his oven after burning Möng Hsu rubies; June 1997. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

In Thailand's Chanthaburi market, Möng Hsu rubies as large as 5 ct are occasionally seen. Smith has purchased a couple stones over 3 ct. for $2500–3000 ct. However, he recently saw a 3.0 ct stone of superfine quality, for which the owners refused an offer of $21,000 (they were holding out for $28,000).

Figure 7 Möng Hsu rubies emerging red-hot from the Mae Sai oven of Somkual Plylaharn; June 1997. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

Figure 7 Möng Hsu rubies emerging red-hot from the Mae Sai oven of Somkual Plylaharn; June 1997. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

Repaired rubies

The Möng Hsu ruby's biggest liability is flux healing of surface-reaching fractures and fissures. Smith told the authors that virtually every stone above 1 ct sent for lab testing comes back with the cancerous comments that evidence of flux healing (labs often term it glass filling) has been found. This was confirmed by then-AIGS Lab Director, Kenneth Scarratt (pers. comm., July 1996). One of the authors (OG) lost so much money due to the flux healing, he stopped buying Möng Hsu ruby altogether.

To most dealers and jewelers, fracture healing with a foreign substance such as flux represents open-heart surgery, not just a haircut. Whether we like it or not, many dealers, jewelers and retail buyers of precious stones do not want to buy stones which have been radically altered in such a way. The idea of flux healing turns them off.

But the biggest problem is something quite simple – when Thai burners first started this type of fracture healing, they did not tell their customers. Customers believed they were buying stones to which only ordinary heat had been applied. When they learned otherwise, they rejected the goods.

Unfortunately, monkeying with stones and not telling the buyer has been business-as-usual in Thailand for years. It started with ordinary heating of corundums (mid-1970s), passed on to glass-filling of surface pits in ruby (1984), surface diffusion of blue sapphire (1988) and now flux fracture-healing (1992).

Figure 8 Heat treatment of Möng Hsu ruby causes a partial resorption of the rutile silk, leaving white silk "skeletons" such as these seen here, looking perpendicular to the c-axis. Reflected light; 60x. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

Figure 8 Heat treatment of Möng Hsu ruby causes a partial resorption of the rutile silk, leaving white silk "skeletons" such as these seen here, looking perpendicular to the c-axis. Reflected light; 60x. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

Market acceptance of ordinary heating was de facto; with no gem lab in Bangkok in the mid-1970s to warn them, foreign buyers generally found out about this difficult-to-identify enhancement only after their inventory was full of heated gems. This was not the case with the other enhancements. A gem-testing lab was founded in Bangkok in 1978. When the glass pit-filling and surface diffusion first appeared in Thailand, these treatments were quickly recognized by Bangkok gemologists and rejected by the global market as a whole.

But the fracture-healing of Möng Hsu rubies was initially passed over by local gemologists, in part because it is difficult to detect and in part because, frankly, certain Bangkok gemologists became overly influenced by traders. Even when they did detect the enhancement, they downplayed its significance, going so far as to declare that it would not be mentioned on identification reports if it wasn't visible under greater than 10x magnification (ICA Gazette, 1994).* Foreign gemologists and dealers were not so kind. Many rejected such flux-healed goods outright, particularly in the important Japanese market.

This has created a very real problem, where the enhancement is generally accepted by Thailand-based dealers/gemologists, but rejected by those outside the country. The result is that goods are returned amidst much name-calling and hand-wringing, a situation from which only lawyers will benefit. Compounding the problem is the fact that laboratories around the world do not have uniform methods of describing or dealing with this enhancement. Some cannot even properly identify it or distinguish between naturally-occurring inclusions and the flux healing.

Figure 9 Looking parallel to the c-axis, the partially resorbed rutile silk is clearly seen. Reflected light; 60x. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

Figure 9 Looking parallel to the c-axis, the partially resorbed rutile silk is clearly seen. Reflected light; 60x. (Photo: R.W. Hughes)

Desperately seeking solutions

So, what to do? First, the gem trade must get together to discuss the problem and explore potential solutions. Today's world is one market, not one-hundred. The global nature of the trade makes it important that solutions also be global, not local.

Then, Thailand's gem traders and treaters need to acknowledge that a mistake was made in not declaring this treatment from the outset. In the strictest sense, the problem is one of the Thai gem trade's own making. Had they been honest in properly labeling their goods from the start, they would not find themselves in this position.

On the other hand, foreign buyers need to acknowledge that some sort of enhancement is needed for Möng Hsu ruby. As anyone who as ever viewed the untreated stone can testify, the Möng Hsu ruby is not a viable gem without enhancement. The enhancement results in a material which is both beautiful and stable. There is certainly nothing wrong with that, so long as it is properly described.

Figure 10 Map of Thailand and Burma, showing the locations of important mines, smuggling towns and major smuggling routes. © R.W. Hughes

Figure 10 Map of Thailand and Burma, showing the locations of important mines, smuggling towns and major smuggling routes. © R.W. Hughes

Overall, we all must stop kidding ourselves. We must realize that, in the eyes of the retail gem customer, the high-temperature heating and flux healing/impregnation of a ruby is not the same as simply cutting and polishing it. No amount of explaining will make it so. A gem which only requires polishing to reveal its beauty is far rarer than something which needs both polishing and ordinary heating. And that is rarer than something like the Möng Hsu ruby, which needs polishing, high-temperature heating and flux-fracture healing. The market should reflect these realities in its descriptions of goods and, most importantly, in its pricing. Remember, gems and jewelry are luxuries. They compete against a number of different goods and services. If we don't start getting our act together, that retail customer will stop buying more than just Möng Hsu rubies.

Postscript

Many gemologists state that the quantity of flux glass found in most specimens is evidence that this infilling is deliberate. But there are many traders who claim such fillings result as an accidental byproduct of the common practice of adding borax (sodium borate) during burning.

To put this matter to rest, in September, 1996, one of the authors (RWH) put the question of borax (flux)-based heat treatment to one of Chanthaburi's best-known burners. This gentleman chuckled at the thought of this being an accident. "Of course we do it on purpose," he said. "Most Möng Hsu ruby is not suitable for faceting without such treatment. We must use borax."

Solutions rarely come easily. But the first step to solving any problem is to discuss it. The authors believe it is far better to discuss problems without solving them that to solve problems without discussion.

Notes

*We refuse to even comment on that silliness.

Further reading

- ICA Gazette (1994) First seven steps to international rules at Asian meeting. ICA Gazette, June, p. 7.

- Emmett, John L. (1999) Fluxes and the heat treatment of ruby and sapphire. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 90–92.

- Hänni, Henry A. (2001) Beobachtungen an hitzegehandeltem Rubin mit künstlicher Rissheilung (Observations on heat-treated ruby with artificially healed fissures). Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gemmologischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 50, No. 3, pp. 123–136.

Author's Afterword

Written in the summer of 1997, this article appeared in the Australian Gemmologist (1998, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 70–74). It also suffers from the all-too common distinction of being rejected by another magazine for being "too controversial" – in this case, the ICA Gazette. I revised it slightly in Jan.–Feb., 2002, mainly to remove the term glass filling, for according to my current knowledge, the process is mainly one of fracture healing rather than fracture filling.

About the Authors

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard's Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology.

Olivier Galibert is a French dealer who has been based in Asia since the late 1980s. He specializes in pearls and fine colored gemstones.

A Reader's Response

Gemologist Adolf Peretti makes the following comment…

Dear Richard,

Congratulations on your website.

While I agree with many of your points, I wanted to contact you on the silk dissolution in Möng Hsu rubies. Untreated Möng Hsu rubies do not have rutile silk, but black and blue zones and zones with hydroxides (e.g., diaspore or boehmite). The whitish particles are produced from titanium in excess from the blue to black titanium-rich zones after heat enhancement and the flakes are heated hydroxide relics which were there also before heat treatment.

Thus two types of whitish particles exist. However, none of them is related to dissolution of rutile silk.

This was the result of a long project four years ago on the same stones before and after heat treatment, published in Gems & Gemology (1995). For more details see our website.

Dr. Adi Peretti (AP)

Richard W. Hughes responds:

In response to Adi Peretti's letter, I took another look at some untreated Möng Hsu rough that I had purchased in the Mae Sai market in 1996 and 1997. Los Angeles gemologist, Martin Guptill, kindly polished flats on many crystals, allowing observation of the interior. Lo and behold, several pieces showed needle inclusions, some with the distinctive knife shape of exsolved rutile. So it appears that exsolved rutile may occur sometimes in Möng Hsu ruby.