In search of ruby and sapphire on the lost Isle of Madagascar.

It is evening in the Madagascan town of Andilamena. In a small restaurant, three Hogmies and one Malagasy pore over a map, intensely focused on a blank spot where no road goes, miles from the nearest settlement. The Hogmies have traveled halfway around the world to visit this miniscule cartographic smudge of tightly wound contour lines. For it is here that Madagascar’s finest sapphires are said to be found. But perhaps I am getting ahead of myself. Let me begin a bit further back…

Madagascar – Sapphire Island at the End of the Universe

PIGMY, noun

One of a tribe of very small men found by ancient travelers in many parts of the world, but by modern in Central Africa only. The Pigmies are so called to distinguish them from the bulkier Caucasians – who are Hogmies. Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary, 1911

My first recollection of Madagascar was grade school, where we dutifully learned that a prehistoric fish, long thought extinct, had been fished from the coastal waters of this errant isle. Later, in gemology class, my teacher again brought up the subject of this forgotten land, mentioning that the famous French naturalist, Alfred Lacroix had written a paper about it (Un Voyage au Pays des Béryls). From that moment on, Madagascar became known to me not just as something out of a Jules Verne novel, but as the “Beryl Island.”

The Island of Madagascar is an anomaly in many respects. While lying just 400 km from the coast of Africa, it was not settled until roughly 2000 years ago, and not by Africans, but by adventurous sailors from the Malayo-Indonesian Archipelago, some 6400 km to the east. Today the country’s human population is a tumultuous stew spiced with Malay, African, Arab, French, Chinese and Indian ingredients.

Madagascar is a wildlife wonderland, as the photo of the lemur above shows. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Madagascar has long been recognized as one of the most biologically diverse spots on the planet. The following will give you some perspective:

- While the California-sized island makes up just 0.4% of the earth’s total landmass, its plant and animal species make up roughly 4% of the planet’s total.

- 80% of Madagascar’s species are endemic, meaning they are found nowhere else on earth.

- Although Madagascar occupies only about 1.9% of the land area of the African region, it has more orchids than the entire African mainland and is home to about 25% of all African plants.

- Close to 100% of all lemur species are found only in Madagascar.

Madagascar owes its biological diversity to geology. Over 165 million years ago, the island was a land-locked plateau at the center of the supercontinent, Gondwanaland. At this time, giant reptiles roamed the earth, while flowering plants and birds were first beginning to appear. Gondwanaland subsequently broke up, leaving Madagascar like a castaway in the Indian Ocean, marooning many of these ancient species. These were further pollinated by plants, animals and humans flying, drifting, swimming, sailing or blowing onto the island, creating a magnificent menagerie unlike any other on the planet.

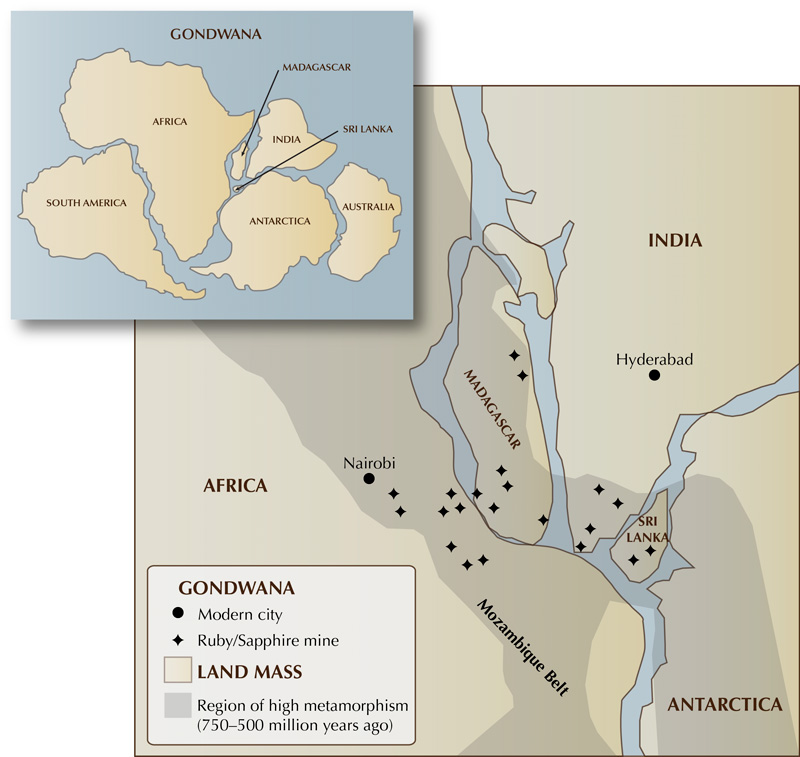

Map of Gondwanaland, showing the position of Madagascar and Sri Lanka relative to the other continents. While Madagascar separated from Africa some 165 million years ago, it separated from India only 88 million years ago. Map: Richard W. Hughes

And what of Madagascar’s spectacular gem diversity? A quick glance at a map of Gondwanaland provides the answer. Before the breakup of that land mass, Madagascar’s nearest neighbors were East Africa, Southern India and Sri Lanka. These regions represent some of the richest gem deposits on the planet. Madagascar lies smack-dab in the middle of precious stone nirvana. It was these precious pebbles that had brought me halfway around the globe. The following is based on my visit in October 2005.

Orientation

The party for this journey consisted of myself, American gem dealer Dana Schorr, and Bangkok-based French gemologist Vincent Pardieu. Vincent was a late, but important addition to the group, not just for his French language skills, but also because he had spent much of the summer of 2005 traveling round Madagascar and East Africa.

Dana and I flew from California to Thailand. From Bangkok, it was a pleasant nine-hour flight to Antananarivo, Madagascar’s capital. Madagascar is literally at the end of the earth. No place on the globe is farther away from my home.

To understand travel in Madagascar, imagine California. Picture a "good" road that goes from San Francisco to Los Angeles and another from Los Angeles to San Diego. And nowhere else. Imagine spending two days driving the 615 "good" kilometers from San Francisco to Los Angeles, then a further three days to cover the 200 "bad" kilometers between LA and San Diego. Now you understand.

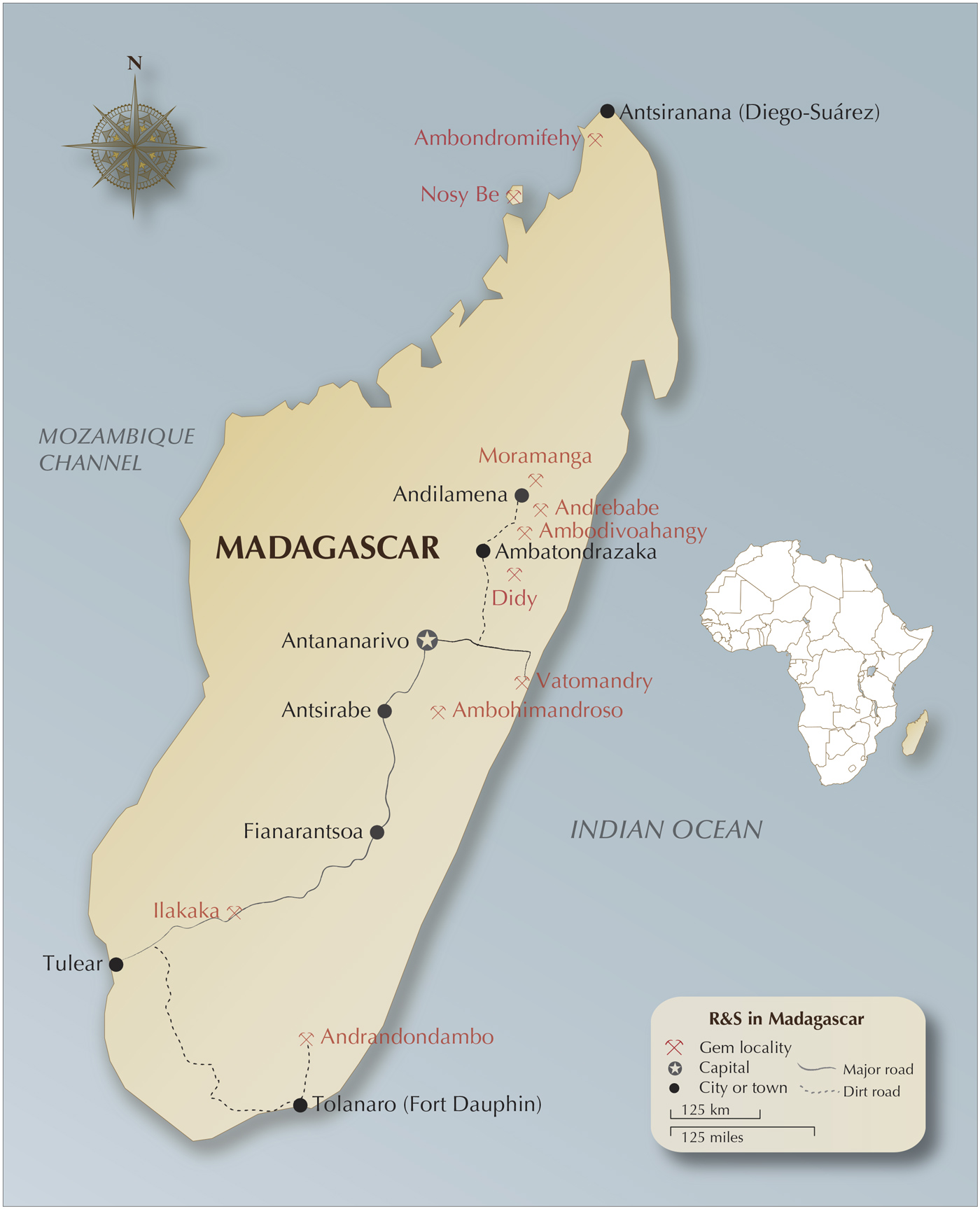

As the map below shows, corundum deposits are found throughout the country; due to the logistical problems of traveling around an island with only two decent roads, we decided to concentrate on the two major corundum-producing areas, Ilakaka in the far south, and Andilamena, a day’s drive north of the capital of Antananarivo.

Map of Madagascar, showing the island's most important corundum localities, along with the author’s route. Map: Richard W. Hughes

Ilakaka

Prior to the discovery of sapphire in October 1998, Ilakaka was just a wide spot in the road. Today it is the center of Madagascar's sapphire universe. Access is via a good road two days’ drive south of the capital. Because this area borders and stretches into Isalo National Park, environmental concerns have complicated the mining situation.

Ilakaka

Once a small hamlet, by 2005 Ilakaka had grown into a major outpost in southern Madagascar. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

The Ilakaka mining area is huge, encompassing perhaps 4000 sq. km. or more. This includes Ilakaka, Sakaraha, Manambo, Voavoa, Fotiyola, Andranolava and Murarano. Currently, the greatest mining activity is taking place south of the Ilakaka–Sakaraha highway, but we witnessed mining all along a belt stretching from Ilakaka to Sakaraha. Large quantities of pink sapphire are produced, as well as blue, violet, orange (including padparadscha), yellow, colorless and other fancy colors. While Ilakaka is famous for the prodigious production of pink sapphires, some extremely fine blue sapphires are also found. Geuda-type sapphire from this region responds well to heat treatment.

A selection of sapphire rough from Ilakaka, Madagascar, showing the broad range of colors produced at this deposit. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Most Ilakaka sapphires are distinguished by large numbers of small rounded zircon inclusions, which occur singly or as clusters. Rough material is waterworn, showing little if any traces of the original crystal shape. Most stones tend to be less than one carat after cutting, but bigger stones are occasionally found. Cut gems above five carats are rare.

Miner’s at Ilakaka’s “Swiss Bank” deposit, so named because of the riches that have been taken from its soil. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

|

The Relais de la Reine Visiting mining localities in Third World nations is often dirty business, where the accommodation is primitive and the food literally catch-as-catch can. Thus we were pleasantly surprised to discover the Relais de la Reine, a jewel of a resort within spitting distance of Ilakaka. Conceived as a midway stopping point along the road between Tulear and Fianarantsoa, the Relais de la Reine was built at the entrance to Isalo National Park long before sapphires were discovered at Ilakaka. Imagine spending the day traipsing hither and yon across dusty roads to distant mines, and then retiring in the evening to the Relais de la Reine, where you will enjoy fine wine and a multi-course gourmet French meal. It is a simple pleasure that simply must be experienced first hand!

The Relais de la Reine resort at Madagascar's Isalo National Park. Photo: Richard W. Hughes |

|

Cargo Cults Why is it that you white people developed so much cargo and brought it to New Guinea, but we black people had little cargo of our own? A New Guinea man to author Jared Diamond Traveling around the world, I have often wondered why some places are so wealthy, while others so poor. In Madagascar, as we chanced upon a dirt-poor village between Ilakaka and Sakaraha with the unlikely name of Bel Air, I again voiced the question. Dana Schorr suggested the answer might be a simple one – geography.

Bel Air, Madagascar. Photo: Richard W. Hughes According to Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel, the East–West alignment of some continents, versus the North–South of others probably played the major role in determining the wealth of nations. While the fossil evidence suggests that all humans originated in Africa, as they spread out around the world, certain regions aided development. In other words, blame it on the weather. How, for example, did Pizarro's 168 Spanish troops defeat Atahuallpa's Incan army numbering some 80,000 soldiers? Diamond argues that the Eurasian continent, with its great East-West geographic expanse, allowed people to travel tremendous distances, sharing both their crops, diseases and ideas. This interchange among a huge geographic, gene and intelligence pool over thousands of years of human history produced peoples that had distinct advantages when they later moved into other parts of the world. Not only did geography allow European and Asian societies to develop superior technologies, but it also assisted development of superior disease resistance. In contrast to Eurasia, Africa, Australia and the Americas stretch largely North–South, across vastly different climate zones, making travel difficult for both crops and animals. This, in turn, restricted the range of the human populations, thus limiting their access to foreign ideas and diseases, making them easy prey when they eventually did come in contact with Eurasian "guns, germs and steel." Diamond's theory (which is not without its critics) offers a possible explanation as to why Madagascar, just 400 km distant from Africa, would be first settled not by Africans, but by Polynesian sailors, who traveled over 6400 km to reach the island. |

Andilamena

The small town of Andilamena lies roughly one day’s drive north of the capital. Ruby and sapphire from this area has been known for over a decade, but it was not until recently that it was extensively mined. The main mining village of Moramanga is located a long day’s walk northeast from the town of Andilamena. Demand in Thailand for low-grade ruby that can be improved by filling fractures with high-RI glass has driven much of the current activity at this mine. A second mining area, Andrebabe, is noted for fine sapphire.

Special permission had to be obtained to visit the mines surrounding this town. This took a full day of cajoling. To protect us, two policemen were sent along as a guard detail. Robberies are not unknown. Just days before we had arrived a West African buyer had been knifed to death in Andilamena. And shortly before Vincent Pardieu’s June 2005 visit to Moramanga, a party of traders was ambushed along the trail. For that reason, Thai and Sri Lankan dealers do not visit the mines themselves, but do all their buying in the town of Andilamena.

Moramanga ruby on sale in Andilamena. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Moramanga

TZETZE (or TSETSE) FLY, noun

An African insect (‘Glossina morsitans’) whose bite is commonly regarded as nature's most efficacious remedy for insomnia, though some patients prefer that of the American novelist (‘Mendax interminabilis’). Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary, 1911

With the exception of the Ilakaka-Sakaraha area, by far the most mining activity in Madagascar is taking place in the hills surrounding Moramanga.

The way to Moramanga involved one hour by road, followed by a combination of jungle walk and boat. If one leaves Andilamena early in the morning, with luck it is possible to be in Moramanga by nightfall. Luck stayed behind, so for us it became a two-day journey, broken in a small riverside village.

A miner examines a piece of ruby rough in Andilamena’s market. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Vincent had warned Dana and I to be ready for some serious mud, but thankfully the track that first day was mostly dry. He had also told us to be prepared for some serious rats, and on this count, did not disappoint. What we were not told was the extent of Vincent’s rat phobia. When the little buggers made their first appearance, running across my feet, Vincent jumped up and started beaming his flashlight into all corners of the crowded hut. I felt like an unwilling participant in an episode of Cops. It didn’t take Dana long to catch on. Every few minutes he would gently tap or scratch the bamboo walls and the hut would immediately shake and shudder as Vincent leapt to his feet, light in hand, to chase away the imaginary vermin. Quite a night. I could almost hear the tsetse flies chuckling in the background.

Dana Schorr on the trail to Moramanga a tough and extremely muddy jungle walk from Andilamena. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

The following day, Vincent’s prediction came true. Mud, serious mud. As we made our way towards Moramanga, we forded one stream after another. Finally, crossing one rise we found ourselves descending into a cauldron of human activity where tiny huts were stacked on top of another like a long brown snake coiling through the jungle. We had arrived at Moramanga.

The author above the village of Moramanga, where 15,000 people claw rubies from the bush. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

The scene was one straight out of America’s gold rush, albeit in a jungle setting. Today, some 15,000 people have carved out a toe-hold from the surrounding forest where they mine for both ruby and sapphire. They mine the hillsides, they mine the river bottoms, they mine the mountaintops. They even mine the muddy effluent-ridden lanes of the town itself. I have seen some spectacular mining camps in my day (Burma’s jade mines come immediately to mind), but I don’t believe I’ve ever seen anything quite like Moramanga, where thousands of miners are living and working literally on top of one another.

Mining the muddy streets of Moramanga. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Andrebabe

HEATHEN, noun

A benighted creature who has the folly to worship something that he can see and feel. Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary, 1911

A day’s walk south of Andilamena is a small jungle encampment at Andrebabe where fine-quality sapphires are found. The area had intrigued me ever since Vincent mentioned it following his visit to Andilamena the previous June. Andrebabe, it seemed, was the sapphire mine at the center of the Island at the end of the universe. The area was said to be populated by pygmies, people said to be descended from the country’s earliest inhabitants. It was also said that they were sorcerers, people with the ability to appear and disappear at will. If we were to visit the area, we were warned we must pay strict attention to fady.

A mysterious clay figure on the road just south of Andilamena. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Among the more curious customs of Madagascar is that of fady. Loosely translated as taboo, it governs to a certain extent the behavior of people with respect to actions one takes, the food one eats and even the days of the week it is “dangerous” to do certain things. While certain fady beliefs are destructive (in the past, twins were sometimes killed or abandoned), others are beneficial. For example, the killing of certain animals is often prohibited, thus aiding conservation efforts. Similarly, the area surrounding tombs is supposed to be left undisturbed, protecting at least some of the rapidly shrinking forests.

The fady custom is further complicated by variations from one region to the next, one family to another, and even on an individual basis. This makes travel for the outsider somewhat problematic, as one is not always aware of just what one is, or is not, supposed to be doing.

Prior to our visit to Andrebabe, we were given strict instructions that all fady must be followed. Now if we could just figure out what they were! The fady were said to include no wearing of red, no killing of animals, no work on certain days of the week. Simple, I thought to myself, I’ll just pretend to be a Hindu Catholic.

We were warned that failure to obey the fady could have dire consequences. Witness the miner at Andrebabe who disobeyed the fady about working on certain days of the week. One day his gem pit filled with water and, as he descended to bail it out, he was attacked by a large eel that had appeared out of nowhere, literally hundreds of miles from the nearest ocean. Ouch! No working on Tuesdays for me. I hate Tuesdays!

A plate of Andrebabe sapphires on offer in Andilamena. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Vincent had actually planned to make the trek to Andrebabe on his previous visit, but was so exhausted upon his return from Moramanga and its rats that he didn’t have the stomach for it. And so, four months later, as we huddled over the map in Andilamena, we batted the idea back and forth. Should we, could we? Finally, a consensus was reached. We’d give it our best shot.

The following morning we assembled for what our guide Gaeton had suggested would be a 15-minute ride to the trailhead. Some ninety minutes later we rolled out of our 4x4 after our driver refused to go further up a track that resembled nothing so much as some devil’s roller coaster. Mother Nature protects her treasures well.

Large creepy-crawlies on the trail to Andrebabe. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

The track contoured up and down a series of ridges as we walked into the mist, all to the accompaniment of ghostly howls from the nearby rainforest. Were these lemurs, or perhaps the sorcerers’ siren songs? I wasn’t about to find out.

After several hours, we came to a house, and a few hundred meters below it, a truck stuck in the mud. The drivers were attempting to winch it up the hill and, at the rate of progress they were making, just might have it to the top by Christmas.

Our Malagasy guide, Gaeton, emerging from a pit at Andrebabe. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Continuing down, we spied Andrebabe peak. A steep downhill stretch brought us to a clearing. As we entered, shifting shadows quickly disappeared into the surrounding forest. Someone had left in a hurry. We had arrived at Andrebabe.

Time was short if we were to avoid being stranded in the forest for the night. We quickly took lunch and then set about exploring the area. Fresh diggings were located in several spots; Vincent and Dana even managed to locate a friendly boa constrictor. All too soon, it was time to go.

And in the end…

ENOUGH, pronoun

All there is in the world if you like it.

Enough is as good as a feast – for that matter

Enougher's as good as a feast for the platter. Arbely C. Strunk

Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary, 1911

And so what of Madagascar, this marvelous menagerie of the peculiar and precious? By the end we were all exhausted. We had toured the desert mines surrounding Ilakaka, traveled by jungle trail and river to Moramanga, we had even traipsed to Andrebabe and lived to tell about it, the first foreign gemologists to do so. No, we did not spy the pigmy sorcerers, nor were Andrebabe’s sapphires the finest we had ever seen, not even the finest on the Island. But they and the rest of Madagascar’s wonders were enough. And enough is just that – enough. A fine feast, one that would keep the Hogmies sated until their return.

Vincent Pardieu and Richard Hughes at the end of a long day's walk to the Andrebabe sapphire mines south of Andilamena. Photo © Richard W. Hughes

References and further reading

- Alfonse, J. [a.k.a. Fonteneau, J.], (1559) Les Voyages Avantureux du Capitaine Ian Alfonce, Sainctongeois. Poitiers, Ian de Marnef.

- Behier, J. (1960) Contribution a la minéralogie de Madagascar. Tananarive, République Malgache Ann. Géol. de Madagascar, 78 pp.

- Flacourt, E de (1658) Histoire de la Grande Isle Madagascar. Paris, Chez G. de Lvyne, 2 Vols. in 1.

- Kiefert, L., Schmetzer, K. et al. (1996) Sapphires from Andranondambo area, Madagascar. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 185–209.

- Lacroix, A. (1912) Un voyage au pays des béryls (Madagascar). La Géographie, Paris, Vol. 26, No. 5, pp. 285–296.

- Lacroix, A. (1913) A trip to Madagascar, the country of beryls. Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution, 1912, pp. 371–382.

- Lacroix, A., 1922, 1923. Minéralogie de Madagascar. Société D’Editions Géographiques, Maritimes et Coloniales, Paris, I, 624 pp.; II, 694 pp.; III, 450 pp.

- Milisenda, C. and Henn, U. (1996) Compositional characteristics of sapphire from a new find in Madagascar. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 177–184.

- Milisenda, C., Henn, U. et al. (2001) New gemstone occurrences in the south-west of Madagascar. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 27, No. 7, pp. 385–394.

- Pardieu, V. (2005) Madagascar: A giant to explore. fieldgemology.org, http://fieldgemology.org/madajune2005.php.

- Pezzotta, F. (2001) Madagascar: A Mineral and Gemstone Paradise. extraLapis English, No. 1, 97 pp.

- Schwarz, D., Kanis, J. et al. (2000) Sapphires from Antsiranana province, northern Madagascar. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 216–233.

- Schwarz, D. and Schmetzer, K. (2001) Rubies from the Vatomandry area, eastern Madagascar. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 27, No. 7, pp. 409–416.

• • • • •

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all those who assisted in his journey, many of whom prefer to remain anonymous. It seems unfair to mention some and not others, so I will simply say that I know who you are and your aid, guidance and friendship has not gone unnoticed. Merci beaucoup! Also, a big thanks to my two traveling companions, Dana Schorr and Vincent Pardieu.

About the authors

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard's Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology.

Vincent Pardieu has held a number of positions in his gemological career. His writings and research can be found at www.fieldgemology.org and at the GIA's website.

Dana Schorr of Schorr Marketing was a Santa Barbara (CA)-based gem dealer and gold trader with three decades of experience in the business. He sat on the Board of Oregon's Desert Sun Mining & Gems, which owns the Ponderosa sunstone mine, and passed away in August 2015.

Notes

Penned in October and December, 2005, following my October 2005 visit to Madagascar. An edited version appeared in The Guide, January–February 2006, Vol. 25, Issue 1, Part 1, pp. 1, 4–6.

|

Other Madagascar Corundum Localities According to Lacroix (1913), the first mention of precious stones in Madagascar was first made by French Captain Jean Fonteneau (a.k.a. Jean Alphonse), who claimed to have found them there in 1547 (Alphonse, 1559). By 1658, Etienne de Flacourt was speaking of the occurrence of topaz, aquamarine, emerald, ruby and sapphire on the Island. But the corundums were largely forgotten until the early 1990s. AndranondamboSapphire at Andranondambo was first reported by French geologist Paul Hibon in the early 1950s, but the modern rediscovery of these gems dates from about 1991. According to one story we heard, a Chinese resident of Antsirabe was offered some blue stones by some Malagasy miners. He thought they might be of some value and so sent them to a friend in Thailand, where they were recognized as sapphires. This set off an Island-wide gem rush that has continued to the present day. To date, the Andranondambo area remains the gold standard for Madagascar blue sapphire, with the finest stones said to come from Tiramene, just north of Andranondambo. Andranondambo sapphires can sometimes be of spectacular quality, in many respects resembling stones from the famous Kashmir, Burma and Sri Lankan mines. Terrific faceted stones of over 20 carats are known. At the time of Vincent Pardieu's visit in June, 2005, an Australian company (S.I.A.M.) was preparing to begin work at the Andranondambo deposit. The far northSapphire occurs in northern Madagascar near both Diego Suarez (at Ambondromifehy) and Nosy Be. In both locales, the corundum is derived from basaltic source rocks, and so tends to occur in green, yellow and inky blue colors. Diego Sapphire

A handful of sapphire from Ambondromifehy, just south of Diego Suarez in Madagascar's far north. Photo: Richard W. Hughes VatomandryThe finest rubies from Madagascar occur near the town of Vatomandry, east of the capital of Antananarivo. The mining areas are at Tetezampaho, Ambidotavolo and Ambodivandrika. The deposit was discovered in September 2000, and soon a rush of miners descended upon the area. In February 2001, the Madagascar government closed the area. At the time of Vincent Pardieu’s June 2005 visit, most miners had left for the Andilamena area. AmbohimandrosoThis deposit, which produces pinkish ruby and pink sapphire, was discovered in late 2004. The main mining area is located at Antsahanandriana, to the east of the road between the capital at Antananarivo and Antsirabe. By January 2005, over 2000 miners swamped the deposit. Like many mining areas in Madagascar, disputes over mining rights have created turmoil and uncertainty. At the time of Vincent Pardieu's visit in June 2005, the deposit was under military lock-and-key.

Ambohimandroso ruby rough on offer in the gem market at Antsirabe. Photo: Richard W. Hughes Other depositsI have just scratched the surface regarding Madagascar's corundum deposits, with the above but a sampling of the more important localities. Incredibly, according to one authority we spoke with, just ten percent of Madagascar is not gem bearing. The future looks very bright, indeed! |