A look at the nexus between gem smuggling and drug smuggling out of Burma (Myanmar), along with the two-faced policies of certain Western governments.

I can already hear the guardians of consensus,

scraping their blunted quills to dismiss this as a "conspiracy theory." Christopher Hitchins

Conspiracy Theory • Gems & Junkies in Burma

From a distance life is simple, every hand the same. Hold yours out and take a look. Highs and lows, ridges and whorls, the maker's strokes, we all have them. Our lives and intellectual development are just like our fingerprints. Begin from a tiny point and spin gently outward, drip-dreary accumulation. Birth, death and what happens in between.

Here I sit, contemplating my hands. Yes, I see the spirals. But also other lines that follow no maker's mold, bold strokes that leap directly from ridge to distant ridge, bypassing the mundane maze of daily drudgery. These raw, wrong-way gashes exist not by grand design, but are unique to me alone. You could call them self-inflicted. Yes, self-inflicted.

In particular, I remember two such slashes. The first was 1973, my sophomore year in high school. The event was the "Saturday Night Massacre" – a political throat slitting – when President Richard Nixon fired Watergate special prosecutor Leon Jaworski. Intellectually riding this thunderbolt to ground shattered the façade so carefully erected by my parents, teachers, preachers and political leaders. From that point on, nothing was the same. Childhood was gone.

The final severing of innocence, though, did not occur until some five years later. I found myself in a small hostelry in the northern Thai opium town of Fang, where a book lurked quietly on the lobby table. It was Alfred McCoy's The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia. Its premise – the US government's war on drugs was a sham. While Washington piously lectured the world on the evils of narcotics and used the hammer of foreign aid to blackmail other governments into doing the same, US intelligence agencies were simultaneously engaged in and supporting countless individuals and groups whose major business was – to paint it black – running dope.

The book was not completely new. I had come across a reference in a magazine a few months earlier, and had actually located a copy in a university library. But seeing it on that table in northern Thailand lent a certain legitimacy. Just a day later, as I walked the jungle paths of nearby opium-growing hill tribe villages, my ex-CIA Shan guide confirmed many of McCoy's statements. This was a terrorist bombing of my middle-American psyche, exploding my final illusions about official behavior. Slash. I entered adulthood.

Coal to Newcastle

A European should never ask a Chinese to take them to an opium den.

Han Suyin

What does this have to do with gems? Patience, grasshopper. Where it enters our discussion is Burma, with the opium trading of the Chinese Kuomintang (KMT). For an understanding of Burma today, including that country's gem trade, one must look to the past, particularly the opium trade in Asia.

While Arab traders first brought opium into China, we will take up the traffic at the time of European expansion during the 17th and 18th centuries. At that time, China's silks, porcelains and teas were in high demand in the West, but round-eyes had little that the Chinese wanted. Scottish woolens just didn't cut it among the more sophisticated Chinese, who demanded payment in gold or silver. This rapidly depleted European treasuries.

In 1773, the British East India Company took control of Indian opium exports to China, an act that fundamentally altered the balance of trade. Using opium to barter for Chinese goods, it was not long before much of China was strung out on a product of which Britain controlled. By the 1790's, the problem was so grave that the Chinese emperor banned the importation of opium. Thereafter, the trade burrowed underground, with British, French and American traders smuggling huge quantities into the Middle Kingdom. In 1839–42 and 1856, Britain and its European/American allies fought two opium wars, slaughtering thousands to force the Chinese to rescind the opium ban.

For those raised on a steady diet of the current "War on Drugs", this may come as a surprise, but it is historical fact. The major Western powers – today so strident in their criticism of Third-World drug production – took up arms to force the Chinese to accept their opium. Indeed, the former British Crown Colony of Hong Kong was founded on the opium trade, ceded to the British as part of the settlement of the first Opium War. Witness such impressive firms as Jardine/Matheson, who were, according to Australian China watcher and professional curmudgeon, Richard Hughes (no relation): "…both Scottish, both religious in the stiff Calvinist way, both scrupulous in financial and personal matters, both indifferent to moralistic reflections on contraband and drugs." (Lintner, 1994).

Simultaneously, Western powers profited from opium monopolies in their various SE Asian colonies. Following the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, they forced the Chinese to cease domestic production of opium, all to maximize their own profits. According to Cockburn and St. Clair (1998):

"The suppression campaign run by the Chinese government had the effect of increasing the demand for processed opium products such as morphine and heroin. Morphine had recently been introduced to the Chinese mainland by Christian missionaries, who used the drug to win converts and gratefully referred to their morphine as Jesus opium.…"

At this point, Chinese opium production moved abroad, southward into Indochina, and most particularly, into Upper Burma, the subject of the current essay.

Enter the KMT

The Republic of China traces its origin back to Dr. Sun Yat Sen and his Kuomintang (KMT) party, who led the successful overthrow of the Qing Dynasty in 1912. Among Sun Yat Sen's followers was a man named Chiang Kai-shek. But unlike the idealistic Sun Yat Sen, Chiang was actually the front man for the "Green Circles Gang," a notorious Chinese triad heavily involved in the narcotics trade (Seagrave, 1985). Before and during World War II, Chiang was heavily supported by the US government, over the protests of people like General Joseph Stillwell, American military attaché to China. According to Stillwell, Chiang was more interested in consolidating his own power against the communists and in profiting from the opium/heroin trade than in fighting the Japanese. Stillwell tried to warn the US about Chiang, but this did not go down well in Washington. Stillwell was eventually recalled and retired during World War II, largely due to his open criticism of Chiang Kai-shek (Tuchman, 1970).

With the 1949 communist takeover of China, Chiang fled to the Chinese island of Formosa (Taiwan), where he set up a government-in-exile. Two divisions of Chiang Kai Shek's KMT troops fled from Yunnan in southern China, to northern Burma (McCoy, 1972).

The Golden Land

In the 19th century, Britain colonized Burma in chunks, grabbing the lower parts in wars in 1824–26 and 1852–53. But it was not until 1886 that they consolidated control over the entire land.

By the close of World War II, imperialism had run its course. In an effort to effect a peaceful transfer of power in Burma, a constitution was created – one with an important safety valve. In order to reach agreement, major minorities (such as the Karen, Kachin, Shan, etc. that together made up close to 50% of the population) would have the right of succession in ten years, should they feel the need.

To fight a war, you need guns. And to buy guns, you need money.

In these mountains, the only money is opium. General Tuan on why his KMT troops were involved in Burma's opium trade

Throughout the 1950's, Burma was wracked by instability, not the least of which involved the two KMT divisions in the north, heavily supported by the CIA. For Washington's cold warriors, destabilization of a country like Burma was of minor importance when compared with potential havoc to communist China. Armed, fed and paid by the CIA, Washington's plan called for KMT troops in Burma to make cross-border raids into China, where the population would unite with them and drive out the godless commies. But like the Cuban Bay of Pigs fiasco a decade later, Mao's army easily repelled the KMT's brief forays. Thus it was not long before the KMT turned to what they and their leaders had been doing for decades – running opium and heroin.

Such was the destabilizing effect of these two KMT divisions, that the Red Chinese did indeed eventually invade Burma. But they did so not for a territorial grab, but at the behest of the Burmese, who were by this time sick and tired of this CIA-sponsored army on its territory. This forced the KMT into northern Thailand, where they continued to receive CIA support, all the while expanding their control over the heroin trade. By the early 1970's, the KMT were said to control 80% of the lucrative Golden Triangle drug trade.

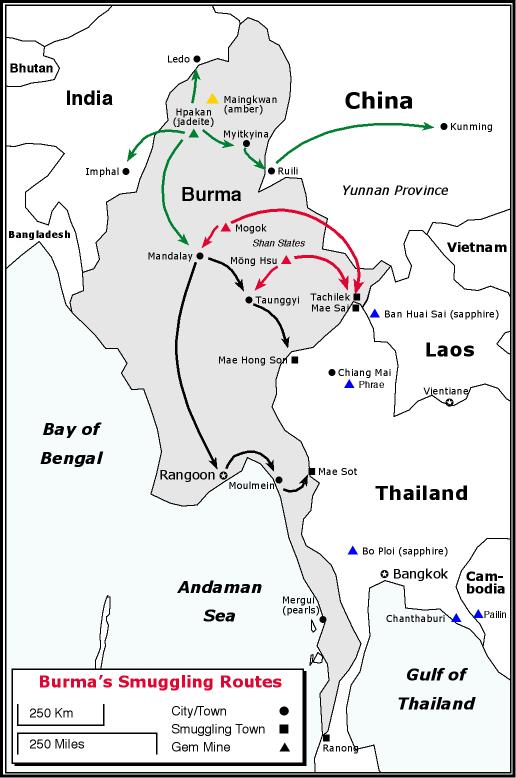

Map of SE Asia, showing the major smuggling routes for gems out of Burma. Map © 2001 R.W. Hughes

Map of SE Asia, showing the major smuggling routes for gems out of Burma. Map © 2001 R.W. Hughes

Alice in Newinderland

With the dawn of the 1960's, Burma was a mess. The few minority groups not already in open rebellion were giving it serious thought. 1962 saw General Ne Win seize power. Tearing asunder the old constitution, he plunged the country into isolation, simultaneously nationalizing industry right down to the street-vendor level. According to Ne Win, this was the "Burmese Road to Socialism," but his own citizens knew better, terming it the "Burmese road to poverty." What a pitiful general. Taking his cues from the ultra-right, Ne Win still couldn't get the trains to run on time. Soon he had reduced what was once SE Asia's richest country to a teetering shadow of its former glory. By the mid-1970's, Burma languished among the poorest of the world's poor – a topsy-turvy unwonderland where the Mad Hatter ruled at gunpoint, while residents cowered under their teacups.

Despite totalitarian rule in the cities, Burma's weak economy produced an ineffective military in the countryside. In many cases, rebel groups such as the KMT, Shan State Army (SSA), Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and Communist Party of Burma (CPB) were better equipped than Rangoon's troops, for they controlled the lucrative border trade. Raw materials such as opium, heroin, jade, rubies and timber fled abroad, being replaced by manufactured products from Thailand. Indeed, so ubiquitous was the Burmese black market that locals referred to it as the "brown market." In Mandalay's notorious night market, one could buy virtually anything – anything, it seems – except a decent government.

Riding shotgun on the smack train

The Thai government seized a large quantity of opium and dumped it into the sea. I asked [Jimmy Yang] if any of the twenty tons had really been dumped in the ocean. "Oh, yes! Oh, yes!" Jimmy laughed. "All twenty tons were dumped into the ocean – but luckily there was a ship in the way. Not an ounce got wet." Sterling Seagrave, Lords of the Rim

Up until 1962, gems were rarely involved with dope. But the nationalization of Burmese industry in the 1960's sent the gem trade underground, where it piggy-backed upon the main contraband of the land – narcotics. With the rise of Ne Win, possession of precious stones in Burma was treated almost as severely as narcotics. Thus it is not surprising the gem trade would choose to ride shotgun on the smack train. Today, despite the liberalization of Burmese laws regarding possession of precious stones, the relationship between drug and gem smuggling continues. Old habits die hard.

Prior to the early 1990's, gem mining was solely the business of the tatmawdaw – the military. With liberalization in the 1990's, government/private joint ventures were permitted. Today the government (read: military) blessing merits a 51.4% majority share, while the private sector does the heavy lifting. All finds are supposed to be declared to, and evaluated by, the government, with anything above a certain value being sent down to Rangoon for auction. This, however, can be avoided if the private party involved pays a 20% tax. Cheaper stones are sold by the partnership and the profits divided according to the share structure.

The clandestine movement of gems out of Burma takes different forms. This involves theft of stones at the mines by individual workers during mining or sorting, or later theft by the private-sector partners or clandestine partnerships between the private sector and individual military officers.

Porters leave the Karen rebel army camp at Wang Kha, bound for Moulmein with Thai manufactured goods. This camp was once a major transit point for Burmese gems smuggled into Thailand, but several years after this photo was taken the Burmese military attacked the site and burned it to the ground. All that remains today are a few charred timbers amidst the ever-encroaching jungle. Photo © R.W. Hughes, ca. 1979–81

Porters leave the Karen rebel army camp at Wang Kha, bound for Moulmein with Thai manufactured goods. This camp was once a major transit point for Burmese gems smuggled into Thailand, but several years after this photo was taken the Burmese military attacked the site and burned it to the ground. All that remains today are a few charred timbers amidst the ever-encroaching jungle. Photo © R.W. Hughes, ca. 1979–81

The Karen rebel market at Wang Kha. Click on the image for a larger version. Photo © R.W. Hughes, ca. 1979–81

The Karen rebel market at Wang Kha. Click on the image for a larger version. Photo © R.W. Hughes, ca. 1979–81

Elephants arrive at Wang Kha. After this photo was taken, the two mahouts climbed down off their rides and undid their longgyis (sarongs), revealing special cotton belts with slots containing silver bars. The silver is only one of many raw materials smuggled out of Burma to pay for manufactured goods in short supply within the country. Photo © R.W. Hughes, ca. 1979–81

Elephants arrive at Wang Kha. After this photo was taken, the two mahouts climbed down off their rides and undid their longgyis (sarongs), revealing special cotton belts with slots containing silver bars. The silver is only one of many raw materials smuggled out of Burma to pay for manufactured goods in short supply within the country. Photo © R.W. Hughes, ca. 1979–81

In other cases, it may be as simple as a Burmese military officer or unit confiscating gems from miners or traders as they make their way abroad. When such seizures are for important gems that cannot be easily concealed, or when there are too many witnesses, the stones are turned over to superiors and may eventually show up in the semi-annual auctions held by the Rangoon junta. But if the seizure is discreet, military officials may themselves arrange private transport and sale in Thailand or, increasingly, China.

Here one enters that age-old tradition of "tribute" payment. Because of the potential profit, postings at the mines and along major smuggling routes are among the most cherry of positions in the Burmese military, and are often obtained by bribing higher-ranking officers. The "tea money" to obtain a position can purchase much more than a cuppa – tens of thousands of dollars may change hands for a particularly lucrative spot. Such is the demand for plum positions that commanders are generally limited to six-month stints, but in the right place, this is more than enough time to enrich oneself.

In many cases, miners and dealers bribe military units for safe passage. They may also travel with the protection of rebel soldiers. Passage through both government and rebel areas is controlled by tax "gates" – checkpoints set up in areas difficult to circumvent – where all goods must be declared (this includes gems, narcotics, timber, gold, silver and other trade products). Taxes are levied as a percentage of value.

One of the consequences of the ban on private ownership of gems in Burma was the appearance of most pieces in cheap base-metal mountings. For once a gem was set in jewelry, it was arguably legal (as personal jewelry). Even today, one sees many Burmese gems traded in these cheap mountings.

Just how the smuggling of precious stones was treated in Burma is illustrated by the case of the infamous SLORC ruby (now renamed the Nawata ruby). This 496-ct golf-ball sized piece of rough was allegedly mined in February of 1990, at Dattaw, in the Mogok area. But the miners did not tell their government overseers. Instead, the stone slipped into Thailand.

Here the story gets a bit murky. One source whispered that a major Thai dealer was shown the piece. When a price could not be agreed upon, the Thai dealer quietly passed the stone's location on to the Burmese military, no doubt with an eye towards future favors. The tatmawdaw then slipped a team of agents into Chiang Mai, Thailand, seizing the piece and its owners. The ruby is now in a museum in Rangoon. And the owners are also back in Burma, albeit at a location underground, having been executed for the crime of removing a piece of earth from the country without informing the government.

|

Burning down the house This night in 1979 fell like a cancer, darkening horizon killing the sun a millimeter at a time. The small Burmese border town of Tachilek had seen thousands like it. But tonight had an attitude. It would be different. Days before, Burmese army troops pried loose a large and valuable jade boulder from a trader traveling through rebel Burma. "Pried" in the form of "gimme and then I kill you." Getting wind of the theft, the Shan State Army (SSA), a rebel group doing battle against the Burmese, decided to take it back. The trick was that the piece was stored in a bank vault in Tachilek, a little powder-keg town that sits astride both the Thai border and a billion-dollar-per-year heroin business. The Shans had a plan. They quietly arranged for the bank's Lahu guards to put down their weapons when the shooting started. However, the Lahus tricked the Shans. Rather than helping the rebels, they informed their Burmese masters, who soon launched a counterattack. Time was short. Blasting through the front door, the Shans entered the bank. Now all that was left was to blow open the vault with a well-placed rocket-propelled grenade. But it was not to be. Once inside, it was obvious that, in the bank's confined spaces, the shooter would become a martyr. And so my ex-CIA Shan friend and his rebel cohorts walked away. Thus ended the skirmish, yet another rumble in a land where the gem trade intersects with politics in a fluid nexus of dope traders and deal makers, spooks and soldiers, politicians and proletarian priests. |

Washy washy

Money laundering is another factor in the relationship between the narcotic and precious-stone trades. Even those of us with decades in this business know how difficult it can be to place a value on a gem. When that stone is in its raw form, multiply the difficulty a hundred-fold. A single valuable piece can make or break a mining operation.

Those in the narcotics business face a different problem. Their goods have both a specific market price and high demand, bringing in barrels of cash, but they must find a way to turn those profits into legal income. What better way than to invest in a gem mine – a cash-and-carry business if ever there was – where a quick appearance of funds can easily be put down to the discovery of a new pocket or even a single stone. And so this is what is done, particularly at the jade mines in Burma's Kachin State. Narcotics traders don't mind sinking huge sums of money into losing ventures, because the money that comes out is now clean, and can be re-invested or banked without fear.

All of this is done with the wink and nod of various bankers and government officials, who, with palm extended, turn bad money into good. The involvement of some of SE Asia's largest banks and trading houses in such activities is fairly well documented (see Seagrave, 1995; Booth, 1999). It is a business that knows no political enemies, a trade where religion, race and politics are immaterial. Such laundry services often find heroin dealers queued next to Mafia dons, beside intelligence agents from the CIA and Mossad, along with terrorists and a plethora of others from the dark side.

The needs of the underworld are obvious. In the case of intelligence agencies, the motive may superficially be less obvious, but dig a bit below the surface and you find similar needs. While ideology might occasionally be involved, all too often it is simply a case of playing power. Money means influence; thus it is something to be collected and used. When funding for black ops is difficult to find in Congress or, more often, when simple greed and lust for power overreaches moral precepts, they visit the underground private sector – both to raise money and later hide its origin. Smuggling of drugs, arms and gems are all involved. The 1980's savings-and-loan scandal in America was a particularly gruesome example of an intelligence agency money-raising operation gone wrong (Stich, 1998), as was the Nugan Hand bank scandal in Australia (Kwitny, 1987). But the whopper of all intelligence money-raising ops had to be CIA involvement in the importation of cocaine into America during the 1980's (à la Iran-Contra) (Webb, 1998; Parry, 1999).

Does this still go on? Think about this: production continues to rise and the money generated is going somewhere. Our current president (G.W. Bush) spent hundreds of millions to get a job which pays but $200,000 per year. At that rate, it will take him hundreds of years just to break even.

There are dirty little secrets, and then there are the whoppers that only the federal government can pull off. The dirty big secret of the money laundering business is that, while us ordinary folk have to report any transaction in excess of $10,000, the exemptions from those regulations are wide enough to drive an entire Enron through. Indeed, those exempt from the US$10,000 transaction reporting regulations include all banks and any company listed on any of the major US stock exchanges. So just guess who washes all that dirty money?

Thus it should really come as no surprise that in 1999, the head of the American Stock Exchange, Richard Grasso, made the ultimate cold call, meeting Colombia’s FARC guerillas in their jungle hideaway, with the idea of getting a piece of the action. When FARC balked at the deal, the US suddenly upped the ante in the war against FARC.

Peace train

Beginning in the early 1990's, the Burmese military began to ease the repression, spurred on by massive riots that nearly toppled the junta in 1988. Slowly private ownership of both gem mines and precious stones was allowed. For the first time since 1962, foreigners were permitted to visit places like the ruby and jade mines. In addition, peace agreements with many rebel groups were signed. These included the Kachin, who controlled most of Burma's jade mines, the Wa, who controlled the important opium-growing areas along the Chinese border, and the Shan.

One such peace agreement saw notorious Shan-Chinese opium warlord, Khun Sa (who in addition to his drug trafficking, was allegedly involved in ruby mining at Möng Hsu) moving down to Rangoon, where he allegedly lives on a military base. Peace has its dividends. Khun Sa was given a franchise for bus services between Rangoon and Taunggyi, capital of the Shan State. Another well-know opium warlord, Lo Hsing-han, along with his son, Steven Law (Lo), is said to have various legitimate business interests. These include a deepwater port in Rangoon, the Leo bus franchise for buses between Rangoon and Upper Burma and a $33-million toll road to the Chinese border through the heart of the opium-growing country. Their Asia World Co., Ltd. is reportedly the biggest business conglomerate in Burma (Irrawaddy Magazine, 2000).

A Kokang Chinese miner emerges from a loodwin at Kadoktut, near Mogok. Photo © 1996 R.W. Hughes

A Kokang Chinese miner emerges from a loodwin at Kadoktut, near Mogok. Photo © 1996 R.W. Hughes

Wa's up?

The Wa are an interesting case. Their territory is perhaps the biggest opium-growing area in Burma. Once feared as head-hunters, after the civil war began they were incorporated into the CPB. In the 1990's, Lo Hsing-Han helped broker a peace agreement between them and the Burmese military junta. As part of the pact, the Wa were given lucrative mining concessions in the Mogok Stone Tract at Kadoktut (Ka Doke Dat). Another part of the agreement was less publicized: it allegedly allowed free trade in all contraband, including heroin and opium.

But if there is any constant in Burma, it is that the situation whirls in perpetual change. Today, many of the clandestine drug labs have switched production to amphetamine, which is flooding neighboring Thailand in ever-increasing amounts. Tomorrow? Who can say.

Simultaneously, Chinese activity in Upper Burma has greatly escalated. Of late, China has been providing much assistance in building roads connecting Yunnan to Mandalay. But this assistance has allegedly been with the caveat that the Burmese move the Wa away from their borders (the Chinese are also not keen on the Wa's drug trafficking). The result has been a massive resettlement action, whereby the Burmese military is pitting the Wa against the Shan along the Thai border. This situation peaked in February, 2001, with a cross-border incursion of Wa into Thai territory near the important ruby-trading nexus of Tachilek/Mae Sai. The Wa's alleged aim was to push Shan rebel troops out of an important drug trafficking route, but the incursion brought the Thai military into play, closing down the border trade and precipitating an international crisis. Although the border reopened in June, 2001, it remains tense.

Between a rock and a morality

With politics, until recently, no one ever accused the stone trade of possessing a case of morality. We did and do what we want, damn the politics and any sort of faux-case of the Mother Theresa blues. But the conflict-diamond issue in Africa has forced us to take a harder look at just where and how we source our products.

Unfortunately, there are no easy solutions. Take Burma. Yes, the sale of Burmese narcotics and precious stones provides some sustenance to a government that would give even Pol Pot a serious run for the wretch-of-the-millennium award. But these same products are traded not only by those aligned with the central government, but also those who oppose it. It's not the product, but the politics, that are the problem.

Bans do not necessarily make something disappear. Even in an Orwellian society such as Burma, where naked fear forces neighbors to inform on one another, the trade in both precious stones and narcotics continues. There is a lesson here, but only if we are open to learning: When a totalitarian regime such as Burma's cannot wipe out these trades, what chance have we in a society that, in principle at least, pays lip service to individual freedom?

If we decide we will no longer purchase Burmese rubies or jade, then for consistency's sake, what about oil from Saudi Arabia? That nation's record on human rights is atrocious, with much of the female population residing only one step above slavery, and its connection to terrorists today is beyond dispute. From Sadaam's Iraq, the Shah's Iran, Somoza's Nicaragua and a host of human-rights assassins stretching all the way from Washington to the tip of Chile, we have and continue to do business with nations with questionable human rights records.

And by what right do we Americans lecture the Burmese about the drug trade when our very own intelligence agencies have both nourished and fed upon it for decades? I am reminded of the British production of Traffik (upon which the US movie, Traffic was based). After the British head of narcotics suppression lectures his Pakistani counterpart about the need to crack down on opium growing, the Pakistani throws the challenge right back: "In my country, alcohol is illegal. Because it is illegal here, I suppose we should demand your Scottish countrymen stop their production of whiskey."

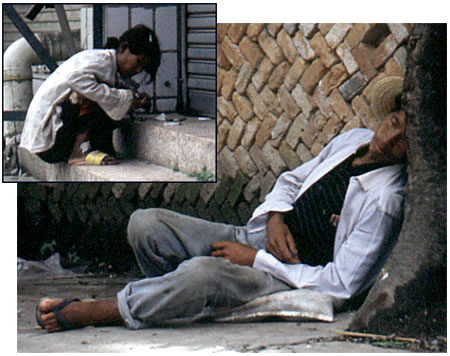

Drug abuse affects not only the West. Here, in Ruili, along the China-Burma border, an addict prepares to shoot heroin (inset), while another lies collapsed against a tree. Although this scene is repeated throughout the skid rows of virtually every major American city, when the drug is something other than alcohol, our leaders call to lock the addict up. Ever ask yourself why? Fact: Deaths from alcohol abuse total far more than all other drugs combined. Photos © Richard W. Hughes, June 2001

Drug abuse affects not only the West. Here, in Ruili, along the China-Burma border, an addict prepares to shoot heroin (inset), while another lies collapsed against a tree. Although this scene is repeated throughout the skid rows of virtually every major American city, when the drug is something other than alcohol, our leaders call to lock the addict up. Ever ask yourself why? Fact: Deaths from alcohol abuse total far more than all other drugs combined. Photos © Richard W. Hughes, June 2001

Closing time

…when young [DEA] agents see that people like Oliver North and Lewis Tambs [former US ambassador to Costa Rica] were banned from Costa Rica for drug running, it's hard for them to accept. They consider this like: "Well, this is a plot. We don't want to believe this." Because, to accept it and to believe it is to accept that your career is a lie. Your chosen goal in life is a total lie. former DEA agent Michael Levine

Closing time. Last call. Here it is, tie everything together, make sense of nonsense and, with ribbon and homily, send all home with the warm-and-fuzzies.

From a distance everything is façile, every hand the same. But look closer. Squint. The lines on our hands are distinct. Trace a life in similar cycles, highs and lows, ridges and whorls, the maker's strokes – simultaneously similar, so much same-same, and yet so individual, so unique.

Priest – politician.

Missionary – journalist.

Peace Corps – Marine Corps.

America destroys a Vietnamese village to save it, the Khmer Rouge an entire nation.

A Chinese religious sect commits "suicide" in police custody, a Texas religious sect the same.

Bomb an embassy in Kenya, bomb an embassy in Belgrade.

Choices made. Always the promise of salvation, but who delivers?

Birth to life to ashes to dust.

Child to student to doctor, medicine man, healer.

Soldier to judge, jury, executioner, mortician.

Silently, we Americans acquiesce, accept the final role, hold up our ideals, shout them to the world, then bury the dead, convincing none but ourselves it's for the common good. Twisted reason, Socrates to Plato. Life is sacred, except when…. Burma, America – black, white.

In the end I find only gray.

I was once a true believer. I saw only black and white. I saluted the flag, recited the pledge, professed belief in a God who never spoke to me. I was an important cog on humanity's most important wheel, a citizen of the greatest nation on earth, ready to die for my country. I rotated my tires on schedule every damned time.

Drugs? Blood diamonds? Ban 'em.

Once that was enough. It took a nation in chains to teach me different. I'm no longer a child. I'll risk my life to protect a friend, a relative, a fellow human. I will not willingly die for an ideology, a religion, a law and most certainly not for some ever-changing line in the sand called “my country.”

Slash! I've reached the age of reason. Nothing's been the same since.

Postscript

When The Guide's Stuart Robertson and Richard Drucker suggested this piece on what many will regard as the height of political incorrectness, my initial reaction was one of slack-jawed awe. And when they printed it, I realized the true meaning of cast-iron cojones.

A wise man once urged writers to do the obvious – write about what they know. Here it is. Putting pen to paper on this subject was more like primal-scream therapy, an exorcism, a ridding of devils. Thanks, guys. You are soul mates, match smugglers for a convicted pyromaniac. Another big thanks to the many Burmese, Chinese, Thais and others of intermediate skin tones who have taken the time to show me their world, to help me see in more than just black and white.

Composed in March–April, 2001, edited slightly afterwards. First published in The Guide (2001, Vol. 20, No. 4, Issue 5, Part 1, Sept.–Oct., pp. 8–14).

Sadly, in August 2003, the US government imposed a full embargo against all Burmese goods. On the surface, this was to punish the Burmese junta. But if you have read this far, you now understand, nothing is exactly as it appears.

See also:

About the author

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard's Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology.

Further reading

- Booth, Martin (1996) Opium: A History. London, Simon & Schuster, 1st English ed., 381 pp.

- Booth, Martin (1999) The Dragon Syndicates: The Global Phenomenon of the Triads. New York, Carroll & Graf, 358 pp.

- Castillo, Celerino & Harmon, Dave (1994) Powderburns: Cocaine, Contras & the Drug War. Mosaic Press, Oakville, Canada.

- Cockburn, Alexander and St. Clair, Jeffrey (1998) White Out: The CIA, Drugs and the Press. New York, Verso, 408 pp.

- Collis, Maurice (1946) Foreign Mud: Being an Account of the Opium Imbroglio at Canton in the 1830's and the Anglo-Chinese War that Followed. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 300 pp.

- Conason, J. (2001) The Bush pardons. Salon, Feb. 27.

- DiNardo, John (1991) Interview with Michael Levine. Undercurrents.

- Hitchens, Christopher (2001) The Trial of Henry Kissenger. Verso Books, 160 pp.

- Hopsicker, Daniel (2001) Barry & 'the Boys': The CIA, the Mob, and America's Secret History. Mad Cow Press, 518 pp.

- Hunt, Linda (1991) Secret Agenda: The United States Government, Nazi Scientists and Project Paperclip 1945 to 1990. New York, St. Martin's Press, 340 pp.

- Kwitny, Jonathan (1987) The Crimes of Patriots: A True Story of Dope, Dirty Money, and the CIA. New York, W.W. Norton, 424 pp.

- Irrawaddy Magazine (2000) Report: Burmese business tycoons, Irrawaddy Magazine, Vol. 8, No. 6, June, 2000.

- Lee, Martin A. and Shlain, Bruce (1985) Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties and Beyond. New York, Grove Press, 345 pp.

- Leveritt, Mara (2001) Asa and me, Arkansas Times, May 25.

- Lintner, Bertil (1994) Burma in Revolt: Opium and Insurgency Since 1948. Boulder, CO, Westview Press, 514 pp.

- McCoy, Alfred W. (1972) The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia. New York, Harper & Row, 472 pp.

- McCoy, Alfred W. (1991) The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade. Brooklyn, New York, Lawrence Hill Books, 635 pp.

- Parry, Robert (1999) Lost History: Contras, Cocaine, the Press & 'Project Truth.' Arlington, VA, The Media Consortium, 304 pp.

- Seagrave, S. (1985) The Soong Dynasty. New York, Harper & Row, 532 pp.

- Seagrave, Sterling (1995) Lords of the Rim: The Invisible Empire of the Overseas Chinese. New York, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 354 pp.

- Stich, Rodney and Russell, T. Conan (1995) Disavow: A CIA Saga of Betrayal. Hallmark Publishers, Reno, NV, 392 pp.

- Stich, Rodney (1998) Defrauding America : Encyclopedia of Secret Operations by the CIA, DEA, and Other Covert Agencies. Diablo Western Press.

- Tuchman, B.W. (1970) Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911–1945. New York, Macmillan Co., 1985 Book of the Month Illustrated Edition, 623 pp.

- Webb, Gary (1998) Dark Alliance: The CIA, the Contras, and the Crack Cocaine Explosion. New York, Seven Stories Press, 548 pp.

Appendix: US government involvement in drug trafficking

Official and unofficial American involvement in drug trafficking is not a recent one. Below is a brief, incomplete timeline:

- Claire Chennault's "Flying Tigers" transporting opium for Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang (KMT) units before, during and after World War II (Cockburn & St. Clair, 1998)

- OSS employment of jailed Mafia kingpin "Lucky" Luciano during World War II (McCoy, 1972)

- OSS (and later CIA) recruitment of notorious Nazi, Klaus Barbie, from 1947 onwards. Barbie later went on to help organize the "cocaine coup" in Bolivia, where a group of right-wing Bolivian generals seized power and reaped billions in the cocaine industry (Cockburn & St. Clair, 1998).

- Support for Chinese Kuomintang units in Upper Burma after the communist takeover in China (McCoy, 1972)

- Project MK-ULTRA, which involved CIA-sponsored testing of drugs such as LSD on unsuspecting patients in a search for mind-control agents (Lee & Shlain, 1985)

- CIA-asset takeover of French opium trading networks in Indochina during the Vietnam War (McCoy, 1972)

- CIA support for Thai, Lao and South Vietnamese generals who were deeply involved in narcotics trafficking during the Vietnam war (McCoy, 1972)

Since the end of the Vietnam war, these policies have continued, and include:

- CIA support for Afghanis and Pakistanis who were heavily involved in the heroin trade during resistance to the Russian invasion of Afghanistan (McCoy, 1991)

- CIA support for Central Americans who were heavily involved in the cocaine trade during the Contra war in Nicaragua in the 1980's (Webb, 1998).

- Sales of helicopters to Colombia for drug suppression, where the sale is related to intense lobbying by US manufacturer, Bell Helicopter.

- Continual undercutting of DEA agents by the CIA, who sought to protect their intelligence assets no matter what criminal activities such assets were involved in (detailed by former DEA agent, Michael Levine) (DiNardo, 1991).

- On Jan. 18, 1993, the soon-to-be-former president George Bush signed a clemency order pardoning Aslam Adam. A Pakistani national, Adam had by then served eight years of a 55-year sentence for smuggling $1.5 million worth of heroin into the United States. He wouldn't have been eligible for parole for another two years. (Conason, 2001)

-

In 2001, newly elected president, George W. Bush, appoints Asa Hutchinson to head up the DEA. Hutchinson was the former federal prosecutor for an district that included the airport at Mena, Arkansas. While prosecutor, he was accused by some of turning a blind eye to CIA drugs and arms smuggling (Leveritt, 2001). Later, while representing the district that includes Mena in Congress, Hutchinson helped support legislation that would ugrade the landing facilities at this backwater airport.

Hutchinson's stated positions include jailing those who post information about marijuana on the internet and opposition to any study of the medical benefits of marijuana, arguing that such studies would undermine the war on drugs. In 1999, Hutchinson criticized government officials for failing to spend federal dollars to persuade voters to reject state initiatives aimed at legalizing medical marijuana. Upon learning that would be in violation of federal law (federal tax dollars may not be used to influence state elections), Hutchinson proposed Congress override the law so that federal monies could be specifically used to influence voters in states with pending drug reform initiatives (Behind the Bushes).

The above is just a shortlist, a quick sip to whet our collective whistles.

|

Ex-DEA Agent Michael Levine Speaks Out Below is a portion of an interview with former DEA agent Michael Levine (DiNardo, 1991): MICHAEL LEVINE: Well, what happened was, the first time that I ran into CIA and other US influences in this "War on Drugs" was on an undercover case that I did into Bangkok, Thailand in 1971, going into 1972. There's no way I can tell you the whole story, but let it end with this: I successfully conned the hell out of [Thai-] Chinese drug dealers who were also the source of an investigation of drug dealers on a case titled, "the Herman Jackson Organization." In essence, Herman Jackson and a bunch of GI's from Vietnam were buying heroin in Thailand and putting the heroin into dead bodies of GI's killed in Vietnam, and the bodies were being funneled through Thailand and then home to the United States. And they were using the bodies of our 19- and 20-year-old young men, killed in that "holy war", as conduits for heroin. Now, at that time, young Michael Levine, young undercover agent – I'm dealing with the same people who are supplying that [Herman Jackson] group. The Chinese drug dealers, who really bought my act, wanted to invite me to a laboratory in Chiang Mai where they were producing hundreds of kilos. Now, this was at a time in our history when the biggest heroin seizure was the "French Connection", sixty-five or sixty-seven kilos of heroin. Now here are people inviting me to a factory that produces hundreds of kilos of heroin a week! Mysteriously – strangely, I was instructed that: "You're not going." The case was ended right at the point I had gone to; that is, at the Chinese dealers in Bangkok itself. Arrests were made. A lot of publicity. The United States government told the American public: "Another great drug war victory." I was told: "There are a lot of things you don't understand. You see, there are priorities." And, of course, I accepted that because I was, again, the "good soldier." Al McCoy's book came out around the same time. Now – when I look back, when I talk about Al McCoy's book and my experience, what I point out is that, even if I had Al McCoy's book in my hands in 1971 and '72 – a book that pointed out clearly why I was not allowed to go to Chiang Mai… what an incredible thing that is to accept! That my own government could protect people who were using our dead GI's – dead young Americans as heroin conduits! How could I accept that? It was just too much! What can I give you as a comparison? It's a man who's been married to a wife who doted on him for twenty years (well, at that point in my [DEA] career it was seven or eight years) whose fidelity he never questioned; and then suddenly coming in and finding her in bed with, not just the postman, but the butcher, the dogcatcher… It's just too much for you to accept as real. Had I had Al McCoy's book in my hands, I would've considered it an un-American thing to read. That's why I can understand what happens to young men who are in law enforcement – why they refuse to look at the reality of this situation. It's just too much for Americans to accept. It's too much for young narcotics agents to accept. You don't take a job like this for civil service security. You take it because you believe in it! And most of these guys do. And then, when these events happen, and they're told: "This is a priority that you don't understand. You just go ahead about your business"… and when they see around them things like Oliver North, who… it's really funny, he's got a book out… I don't even want to say the title – but I looked in the index and he's got three pages devoted to drug trafficking, yet, in his own notebooks (he's got twenty 600-page notebooks) he's got 500 pages of notations about drug trafficking. There's something he's not telling us, you know? So, when young agents see things like this… when young agents see that people like Oliver North and Lewis Tambs [former US ambassador to Costa Rica] were banned from Costa Rica for drug running, it's hard for them to accept. They consider this like: "Well this is a plot. We don't want to believe this." Because, to accept it and to believe it is to accept that your career is a lie. Your chosen goal in life is a total lie. |