Fiber-optic lighting is one of the most useful form of lighting in the gemological laboratory. With it, we are able to see inclusions that would otherwise be invisible.

Fiber-Optic Light in Gemology • Living in the Dark AgesWhat I give form to in daylight is only one per cent of what I have seen in darkness. M.C. Escher (1898–1972)

A gemologist’s life would be far easier if gems were cut as parallel-sided plates. But they’re not. Facets are designed to reflect light back to the viewer, not transmit it. This means light entering the gemstone from behind (transmitted light) will typically not pass straight through. If we want to see inclusions, we must constantly change the light paths through the gemstone. This is done by changing the position of the gemstone relative to the light and changing the light relative to the gem. The most versatile and controllable method of doing this is with the fiber-optic light, an illumination technique “darker” than even darkfield.

During a recent routine identification of a natural chrysoberyl a startling difference in two distinctly different types of illumination commonly used in the examination of gemstones was clearly revealed. These two methods are darkfield and fiber-optic illumination.

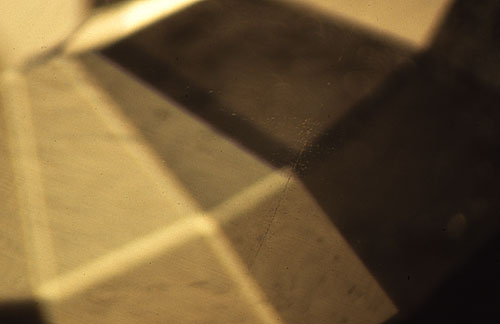

When this chrysoberyl was studied in darkfield (Figure 1), only a fine linear growth band was seen. However, when fiber-optic lighting was directed in along the girdle plane, bundles of fine light-scattering silky needles extending at 90˚ from the linear growth band became abundantly clear. At the same time the linear growth band itself was also more clearly detailed (Figure 2). The difference in the amount of visual information provided by these two different lighting techniques was startling. In this instance darkfield was clearly inferior to fiber-optic illumination.

Figure 1. The darkfield view of the interior of this natural chrysoberyl provides very little detail to the gemologist. Only a fine linear growth band is revealed. Magnified 10×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

Figure 1. The darkfield view of the interior of this natural chrysoberyl provides very little detail to the gemologist. Only a fine linear growth band is revealed. Magnified 10×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

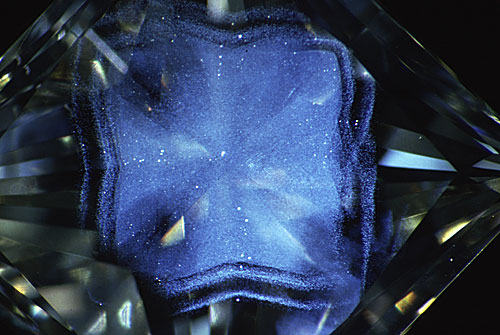

Figure 2. When fiber-optic illumination is used on the same chrysoberyl, bundles of fine light-scattering silky needles are seen extending at 90˚ from the linear growth band which is also more clearly detailed now. With fiber optics a tremendous amount of detail is gained. Magnified 10×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

Figure 2. When fiber-optic illumination is used on the same chrysoberyl, bundles of fine light-scattering silky needles are seen extending at 90˚ from the linear growth band which is also more clearly detailed now. With fiber optics a tremendous amount of detail is gained. Magnified 10×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

For decades, darkfield illumination has been considered the most useful illumination technique in gemological microscopy. Darkfield gained widespread acceptance in gemology primarily because it is the method used internationally in diamond grading, and as such virtually all gemological microscopes manufactured today come with a built in darkfield system. Simply flip the switch or turn the knob and the darkfield system is ready to use…simple and convenient.

As a result of this, darkfield illumination is the lighting technique most gemologists use for colored stones and diamonds. Most jewelers and appraisers rely almost entirely on darkfield illumination in their gemological work with a microscope. Darkfield illumination as married to the gemological microscope is what is taught, and darkfield illumination is what is sold as the "built-in" illumination system on today’s advanced gemological microscopes.

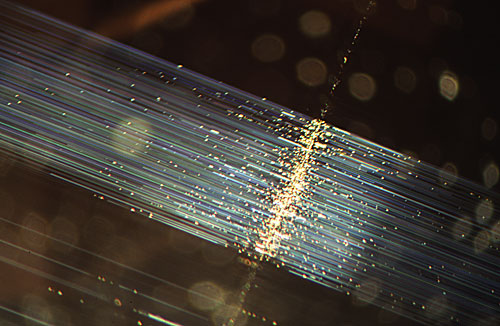

For skilled laboratory gemologists however, fiber-optic illumination is now considered to be the single most useful form of lighting in gemology for gem identification. What is missed in darkfield (Figure 3) is often visible in fiber-optic lighting (Figure 4), as is the case with the ultra-fine directionally visible particles of flux known descriptively as "rain" that are found in Kashan flux-grown synthetic rubies.

Figure 3. Using darkfield illumination this Kashan flux-grown synthetic ruby looks virtually flawless. Magnified 15×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

Figure 3. Using darkfield illumination this Kashan flux-grown synthetic ruby looks virtually flawless. Magnified 15×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

Figure 4. Fiber-optic illumination reveals the rain-like stringers of flux particles in the Kashan ruby that are so typical of this type of synthetic. Magnified 15×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

Figure 4. Fiber-optic illumination reveals the rain-like stringers of flux particles in the Kashan ruby that are so typical of this type of synthetic. Magnified 15×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

Certainly darkfield illumination still has its place in diamond clarity grading since a uniform standard for lighting is most useful in diamond grading production work. However, even in diamond grading darkfield can prove to be inadequate and through its exclusive use interesting and major features can be overlooked or underestimated. One previously published example is the four point stellate cloud described in Gems & Gemology (Spring 2001, pages 58–59). Another is provided by comparing the low-power darkfield photomicrograph of a light green diamond shown here in Figure 5 with the fiber-optic illuminated image shown in Figure 6 in one and the same diamond. The darkfield image is the one that a diamond grader would see, while the one illuminated by a fiber-optic light wand is what the gem identification specialist would observe. There is obviously a big difference in the amount of detail lost through darkfield and revealed with fiber-optic illumination.

Figure 5. In darkfield illumination only a vague image of a cloud of pinpoint inclusions is visible in this pale green diamond. Magnified 10×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

Figure 5. In darkfield illumination only a vague image of a cloud of pinpoint inclusions is visible in this pale green diamond. Magnified 10×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

Figure 6. When fiber-optic illumination is used on this same green diamond, the details of an amazing phantom cloud become visible. How many significant features in diamonds have been overlooked because of inadequate darkfield lighting? Magnified 10×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

Figure 6. When fiber-optic illumination is used on this same green diamond, the details of an amazing phantom cloud become visible. How many significant features in diamonds have been overlooked because of inadequate darkfield lighting? Magnified 10×. Photomicrograph © John I. Koivula, microWorld of Gems.

Given the complexity of today's gemological problems it doesn't seem possible for anyone on the technical side of the gem industry to get along without fiber-optic illumination. As shown in this article, at the microscopic level there are internal characteristics in gems that you just cannot see without fiber-optic lighting. If you are still using darkfield almost exclusively with your microscope, then you are living in the dark ages of gemological microscopy.

While you might be content to live in the dark ages, this is one instance where you'd be better off going into the light. Step into the light and get yourself a fiber-optic illuminator. You might be surprised what you’ve been missing. Remember, just because you don’t see it, doesn’t mean it isn’t there.

Figure 7. A fiber-optic system such as that shown above offers unparalleled illumination. Shown are both a stiff “goose-neck” light guide, which is good for photography and a flexible rubber-sheathed light guide, which is best for everyday use. The flexible light guide has a pinpoint illuminator extension, which is also quite useful. Photo: Richard Hughes.

Figure 7. A fiber-optic system such as that shown above offers unparalleled illumination. Shown are both a stiff “goose-neck” light guide, which is good for photography and a flexible rubber-sheathed light guide, which is best for everyday use. The flexible light guide has a pinpoint illuminator extension, which is also quite useful. Photo: Richard Hughes.

About the authors

John Koivula is the author of the magnificent Photoatlas of Inclusions in Gemstones, Vols. 1–3, along with several other books and over 800 articles. He is currently Chief Research Gemologist at the Gemological Institute of America and is the world's foremost gem photomicrographer. John was also the scientific advisor to the famous MacGyver television series. Many of his books and enlargements of his images are available through microWorldofGems.com.

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard's Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology.

Notes

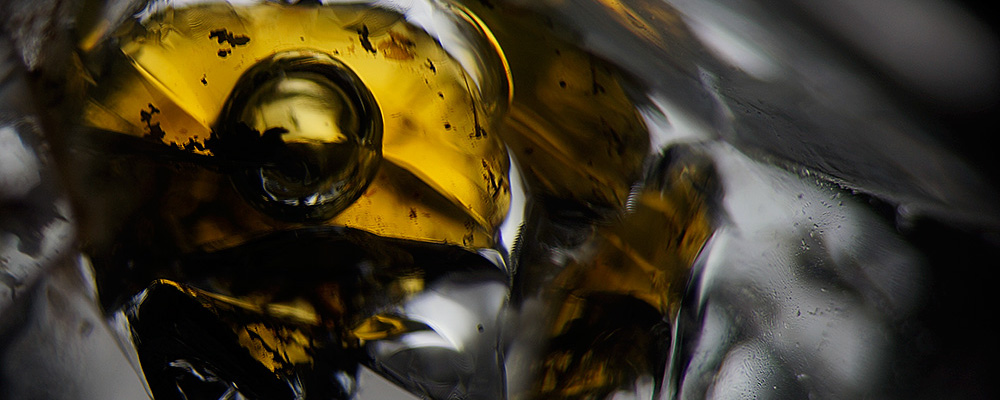

First published in July 2005, while John and I were at the AGTA GTC. Working with John was one of the greatest pleasures of my life, sadly far too brief. Looking back, I can only wonder what might have been… Title image is petroleum inclusion in a quartz from Pakistan. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul