The mining of natural red andesine in Tibet has been a subject of controversy. This article describes RWH's second visit to the Tibetan deposit.

Tibet Andesine Mines • Part 2 • Faith

It is wiser to find out than to suppose. Mark Twain

Unfinished bid'ness

My close friend Vincent Pardieu has often remarked that he hates unfinished business. Vince and I both understand that a brief visit to a deposit is rarely enough to fully characterize it. Thus we continue to return to places we have already been, and every time the experience is fresh and we learn new things. Mines are not static entities, but continually change like the ground that is worked.

The Tibetan andesine deposits represent unfinished business. Thus when my wife, daughter and I were discussing where we might go on holiday, I gently suggested Tibet. We could go to Lhasa and even Everest Base Camp. They quickly agreed. I also talked an andesine skeptic into joining us. Dana "Sapaba" Schorr sits on the board of Oregon's Ponderosa sunstone mine and was the first person to mention the possibility of andesine treatment to me (Hughes, 2011). If anyone could snuff out a scam, Sapaba would be the one. And so it was. We set off for Tibet and another great adventure.

Railway to the moon

Railway to the moon

Rather than flying directly into Lhasa, our party boarded the train in Guangzhou for a two-and-a-half day trip to the "roof of the world." The train's compartments are pressurized like an airplane, so that acclimatization from the trip is minimal. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Our journey began in Hong Kong, with a two-hour trip to Guangzhou, where we met the train to Tibet. The rail link between Tibet and the rest of China was completed in 2006. From Guangzhou, the line heads north via Zhengzhou, then trends west, through Xi'an and Xining before entering Tibet. Along the way, the train goes through the Fenghuoshan tunnel (the world's highest railway tunnel at 4,905 m; 16,092 ft), and over the Tanggula Pass (5,072 m; 16,640 ft), before dropping down to Lhasa at a balmy 3,490 m (11,450 ft). Total travel time: 56 hours.

Trainspotting

Trainspotting

Dana Schorr admires the scenery on the Qinghai-Tibet railway. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Goal No. 1 after arrival in Lhasa was catching our breath. Whew! The train is actually pressurized like an airplane and so, despite the lengthy journey, it did nothing to help acclimatization. Stepping off the train was to enter another world. Thankfully we would spend the following day in Lhasa before heading out to higher climes.

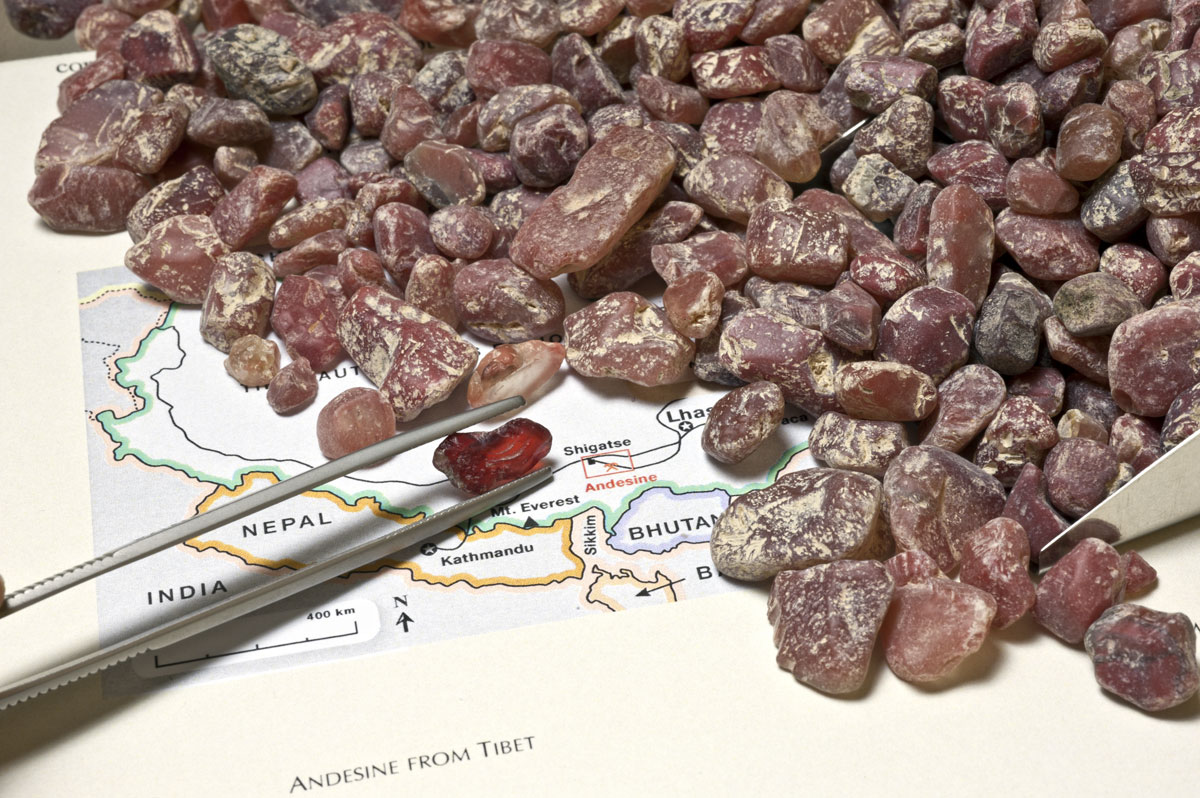

Map of Tibet, showing the location of the andesine mines. Map: Richard W. Hughes

Map of Tibet, showing the location of the andesine mines. Map: Richard W. Hughes

Lovely Lhasa

Lhasa is nothing if not stunning. With the Potala palace atop a hill dominating the city and the stream of pilgrims demonstrating their faith by spinning prayer wheels and walking kora (holy circuits), there is no place quite like it in the world.

The morning after our arrival, we began climbing up the steps of the Potala. Winding through its rumored 10,000 rooms, we followed throngs of pilgrims back into time. At each major site along the way, they made offerings and poured oil into the candlelight bowls that keep each room lit. Many came as families, with younger generations helping to hoist the elderly up and down the building’s steep stairwells. We joined them in spinning prayer wheels on the perimeter of the palace as they worked their way towards heaven.

Perfect darkness

Perfect darkness

Lhasa's Potala palace floats ghostlike above the darkened city. Photo: Billie Hughes

Afterwards we stopped for lunch—yak and yak butter tea, of course. The meat is prepared a number of ways—yak steak, momos (dumplings), stew, meatballs, hamburgers—the animal’s presence is pervasive in quotidian life. In fact, many Tibetans eat only the meat of larger animals. It is better to take one life that will provide many meals, they believe, than having to take many lives of smaller animals for sustenance.

We continued to the Jokhang monastery, Tibet's holiest, and then walked around the bustling market in the historical part of town. Again, people could be seen spinning their own handheld prayer wheels while whispering prayers. Om mani padme hum, om mani padme hum (the jewel is in the lotus).

To Base Camp

The following day we set out for the major goal of our trip, the north base camp of the highest peak on the planet. Known as Sagarmatha to the Nepalese and Chomolangma to the Tibetans, this peak and the rest of the Himalayas were formed by the continental train wreck of the Indian subcontinent and the Asian plate. Formerly an ocean bottom (the Tethys Sea), what is now the Tibetan plateau was rudely forced upward as the Indian subcontinent slid below. This cataclysmic geological event not only gave rise to the world's greatest mountain chain, but resulted in the formation of numerous mineral deposits, including andesine. No superlatives can do justice to this region. It continues to both rise (10 mm per year on Nanga Parbat) and erode (2–12 mm) faster than any other place on the planet.

Ancient wisdom

Ancient wisdom

Tibetan man offering fossils for sale atop, Tropou La (4500 m; 14,763 ft). Before the collision with the Indian subcontinent, Tibet was a sea, and marine fossils are thus found throughout the land. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Twistin' an' turnin' in Tibet

Twistin' an' turnin' in Tibet

At 8848 m (29,028 ft), Mount Everest lies in a region that contains many of the world's highest peaks. The northern base camp is eight hours' drive west of Shigatse, with the road winding over two major passes. In this photo, taken atop Pang La (5050 m; 16,568 ft), Everest lies behind the clouds in the distance. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Goal!

Goal!

Dana Schorr, Billie Hughes, Wimon Manorotkul and Richard Hughes at the north base camp of Mt. Everest (Mt. Qomolangma). At 5200 m (17,060 ft), it is cold even at the height of summer.

I see you

I see you

The top of Mt. Everest (Mt. Qomolangma) as seen from Tibet's north base camp. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Mount Everest's north base camp lies just beyond Rongbuk monastery, a day's drive beyond Shigatse. Sadly the weather was cloudy, affording us just brief glimpses of this giant peak.

Kala Patar

Kala Patar

Richard Hughes at Kala Patar above Gorak Shep in Nepal's Khumbu District, with Mt. Everest (center; 8848 m; 29,028 ft) in the background (2003). The author visited Everest from the Nepalese side in 1977 and 2003, but always dreamed of seeing it from the north. The top of Everest (above the yellow band) is actually limestone containing tiny marine fossils. Lhotse (8,414 m; 27,605 ft), fourth highest mountain in the world, dominates the scene to the right of Everest. Photo: Olivier Galibert

Andesine at last

After returning to Shigatse from Everest base camp, we made plans for the second objective of our trip. The next day we would stop at the andesine deposit at Zha Lin, some 60 km southeast of Shigatse.

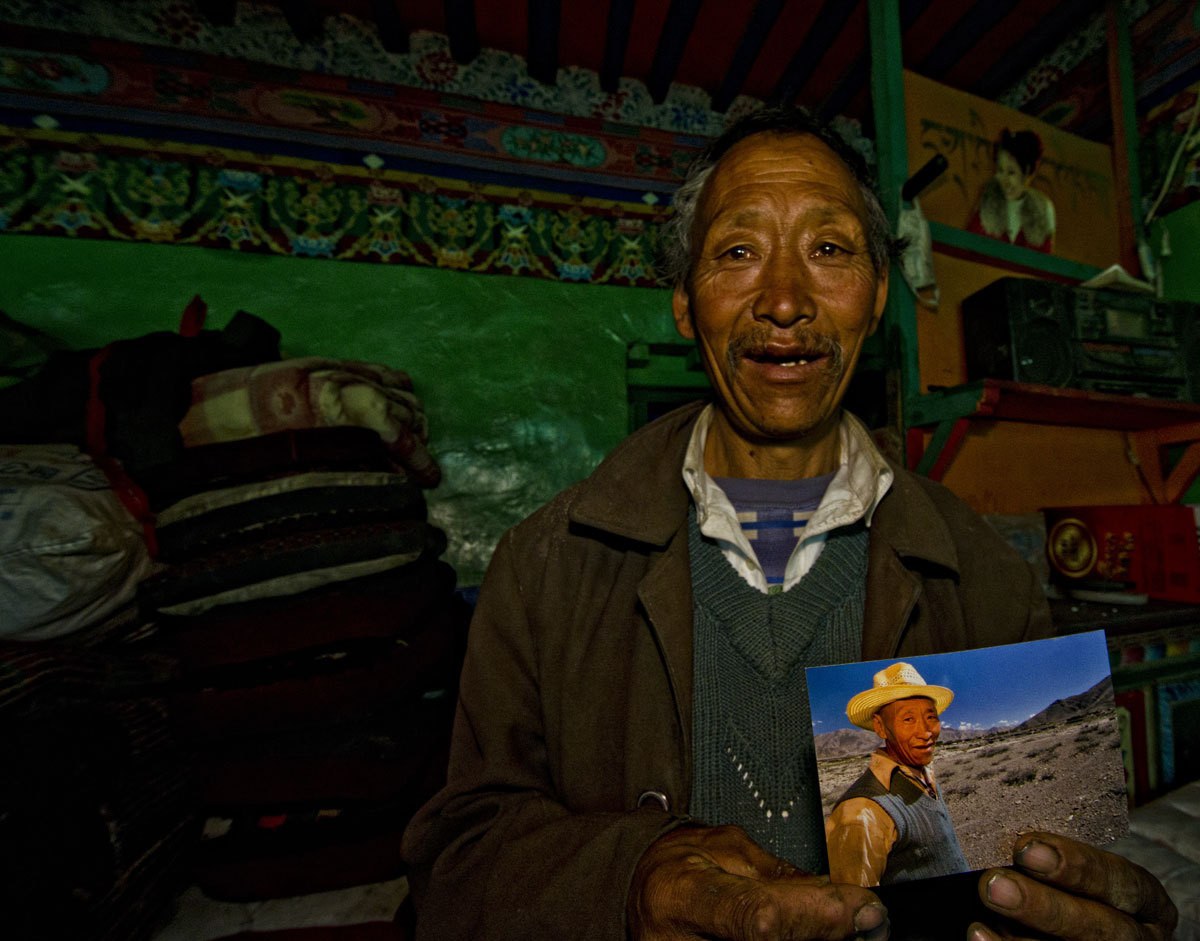

Prior to our arrival in Tibet we printed photos of some of the people I had met a year earlier. Our guide and driver were not told in advance of our plans to stop in the village, nor was anyone from our previous trip informed.

After locating the correct village (Dhongtso 5, aka Zha Lin; 3,929 m; 12,891 ft), we stopped and our guide showed a woman the pictures I had previously taken. She quickly led us to the house of Trilnen Dhongtso, who smiled broadly when he saw his picture. He said that many tourists took pictures, but we were the first to give him one, and he was delighted.

Happiness is…

Happiness is…

Trilnen Dhongtso of Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin) village holding a picture of him shot the previous year. He told RWH that many tourists came and took pictures and promised to send them, but RWH was the first who had actually given him a photo. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

With the help of our Tibetan guide, who spoke excellent English, we asked him if they found red stones in the area. He answered that they did. We asked him if people brought them from other places and he said no, they were found in the area, behind the village, and at another place about four hours' walk away. He then brought out a bag of the stones, telling us that normally they collected them in the dry season (October through June) and sold them to traders. He said this was the last bag he had left, with the production from the previous season having already been sold. Would we like to buy it? We said we would, but only if we could collect a few stones ourselves and keep those, too. He said that would be fine, but we could only collect stones on the ground behind the village, not dig for them in the mountains as that would upset the mountain gods and result in severe lightning storms and flooding.

Lay your hands on me

Lay your hands on me

A parcel of approximately 1750 carats (525 pcs; average size = 3.34 cts) of Tibetan andesine purchased by Richard Hughes at Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin) on 20 August, 2011. The seller told the author that andesine is typically collected in the dry season (October–June) and that all of the village's other parcels had already been sold. These specimens later proved to be gemologically identical to those hand collected in the field. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Do you want some tea, grandpa?

Do you want some tea, grandpa?

Wimon Manorotkul enjoying a bit of Tibetan hospitality in Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin) village. Tsampa (roasted barley flour) and Tibetan tea make for a delicious snack. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Following the typical Tibetan hospitality of salted butter tea and tsampa, we purchased the parcel, giving the rest of the pictures to one of the women to distribute to the other villagers. We then walked behind the village to do some collecting of our own.

Andesine waves of grain

Andesine waves of grain

Dana Schorr, a director of Oregon's Ponderosa sunstone mine enters the valley behind Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin; 3,929 m; 12,891 ft) village with our Tibetan guide. Just past the barley fields lies one of Tibet's andesine deposits. 20 August, 2011. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Exiting the village, we carefully made our way along the levee dikes that separate the different barley plots. It had been an extremely wet summer and the barley was green and high. Eventually we reached the alluvial fan where in 2010 we had previously collected specimens. No one from the village accompanied us. It was just our guide, Dana Schorr and myself.

Reaching the collection site, I spied a young boy herding sheep near the hillside. Through our guide, we asked him if they found red stones in the area and he answered that yes, they did. Completely unprompted, he then immediately walked to the area we had dug the previous year and within a minute or two had located a small piece. His young friend then wandered over and the five of us spent the next hour collecting specimens by hand. Samples were carefully segregated. Those personally found by Schorr or myself went into one lot. Anything found by the Tibetans went into a separate lot. Both were kept separate from specimens purchased in the village.

Tibet

Tibet

Two young Tibetan shepherds showing off the andesine specimens that they helped Richard Hughes and Dana Schorr collect at Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin) on 20 August, 2011. These teenage boys had no advance notice of the arrival of Hughes and Schorr, nor did they have any communication with anyone in the village prior to our arrival at the collection point. And yet they had no problem immediately pointing out where andesine could be collected when asked. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Seeing red

Seeing red

A Tibetan shepherd points out a small piece of andesine partially embedded in the soil at Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin). Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Floater

Floater

While most of the andesines collected by Richard Hughes and Dana Schorr at Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin) were partially embedded in the soil, some were entirely floating upon the surface. In the bright sunlight these contrasted dramatically with the surrounding soil and rocks. This piece is an example of a "floater." It is no different from other nearby "floating" rocks, except that it has an attractive color. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Hand-collected andesines from Zha Lin

Hand-collected andesines from Zha Lin

The above andesines were hand-collected by Richard Hughes and Dana Schorr on August 20, 2011 at Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin). The top group of six specimens shows the top surfaces as they were found, while the lower group shows the underside of the same six specimens. The specimen at lower right in each group was a "floater" found completely free on the surface, while the other five were partially embedded in the ground. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Labtime: A little knowledge is a strangerous thing

One of the key issues facing gemologists trying to verify the Tibetan andesine deposits was the paucity of time at the field sites. This was due to a combination of politics and environment. The Tibetan Special Autonomous Region (SAR) has been the scene of almost continuous political instability since the Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959. As a result, the movement of foreigners and even Chinese citizens is heavily restricted. Special permits are required to enter Tibet and the Chinese government stopped issuing permits to both foreign and Chinese tourists for the entire month of July, 2011 (Leadbeater, 2011).

The second factor is elevation. Much of Tibet lies above 4000 m (13,123 ft), and this includes the andesine deposits at Bainang/Zha Lin/Yu Lin Gu. It is extremely difficult to move at those elevations and even the hardiest travelers experience symptoms of Acute Mountain Sickness. This is compounded when only a few days are available for field work.

But the biggest problem was conflicting data regarding the specimens that were collected on site. Two features were particularly troubling. The first was glassy residues found on the surfaces of many specimens. Were these the result of salting the deposit with treated specimens? Or could they have been formed by the heat generated during the formation and subsequent volcanic eruptions that brought the crystals to the surface? Following the study of numerous specimens, it appears that the latter is the case.

The second problem was conflicting argon release data. The first specimens tested by Dr. George Rossman at CalTech (Rossman, 2009) showed argon levels that were very similar to specimens thought to be diffusion treated, and far below the argon levels found in untreated rough from Inner Mongolia. Subsequent testing by Rossman (2011a, b) and Peretti & Villa, et al. (2011) in Switzerland revealed argon levels that showed a broad range, particularly when the experiments were run at different temperatures. The latter produced more complex results that suggested the Tibetan stones were subjected to different thermal events in nature, with some being degassed to a much higher degree than others.

Sampling

Sampling

A small group of a large lot of andesine purchased in Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin) village by Richard W. Hughes on 20 August, 2011. Stones ranged in size from less than 0.25 cts to over 10 cts each. Internet critics have suggested that parcels of stones collected by gemologists in Tibet have been too uniform in size and quality to be real. The stones that I have seen, hand collected and purchased have been nothing of the kind, as the above photo shows. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

In the end, the proof of the natural origin of Tibetan andesines has come from several different directions. Ahmadjan Abduriyim (Abduriyim, 2011) and Adolf Peretti (Peretti & Villa, et al., 2011) both detected silver (Ag) in Tibetan stones and to date this has not been found in any andesines thought to be treated. Gold (Au) has also now been found, along with traces of uranium (U) and thorium (Th). Copper isotope studies have also shown differences between the untreated Tibetan stone and the treated stones from Inner Mongolia. Analysis of fluid inclusions by Peretti and his team have also shown contents (sulfur and copper) that are strongly suggestive of natural origin, with no signs of negative crystal damage bursts (decrepitation halos; Peretti & Villa, et al., 2011). When a lava erupts, the pressures are still relatively high, whereas artificial diffusion treatment is done at normal pressures and thus would likely produce negative crystal decrepitation.

Significantly, those who were once skeptical about Tibetan andesine (Rossman, 2009; Fontaine, et al., 2010) have, after further testing of additional specimens, revised their opinions regarding the Tibetan stone (Peretti & Villa, et al., 2011; Rossman, 2011b). Few of us take pleasure in altering our previous positions. The idea that they would voice findings contradicting their former standpoints speaks volumes about their integrity and the validity of the scientific process, whereby findings are published and subjected to critical review. One can argue about interpretation of data, but the idea that has been suggested by some that the individuals involved have somehow been "bought" is completely contradicted by the evidence.

Hmmm…

Skeptics will argue that the Tibetan deposit might have been salted with stones from elsewhere. One critic told the author that Zha Lin could have been faked prior to our 2010 visit by pounding a "rebar" rod into the ground, dropping a stone into the hole, and then covering it up. Assuming you could easily get a rod into a soil made up of compacted and often flattened glacial rock fragments, this still would have entailed hammering thousands of little holes to ensure that our party would find something, because we dug holes across an area covering several hectares and in places (such as under bushes) where they had no idea we would dig. The previous gemological expeditions to this region reported no excavations beneath bushes.

Thus when this gentleman floated that notion, I told him I had dug in the Tibetan soil (with great difficulty) and suggested he do the same and get back to me. To date, he has not. And there is, of course, that tiny inconvenient truth: advanced testing on these stones shows them to be untreated and provably different from feldspars from Oregon and/or Mexico.

I'm RG, You're GR, it's all OK

I'm RG, You're GR, it's all OK

Two Tibetan andesines showing different patterns of color zoning. The specimen at left was obtained by the author at the Tibetan andesine deposit in 2010 and shows a green core with a red rim. That at right was obtained at the Tibetan andesine deposit in August, 2011 and shows the reverse. While some gemologists have suggested that the zoning pattern can be used to identify treated andesines (with only the untreated Oregon stone showing a green skin and red core), this is not the case. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Entering the Matrix

But still there were skeptics. Where are the matrix specimens? We refuse to believe unless there are verified matrix specimens.

The planet is loaded with countless mineral deposits where not a single gem specimen has ever been found in matrix, and yet the deposits are beyond real. Over 2500 years of intensive mining in Sri Lanka has taken place with nary a stone being found in matrix. The sapphire deposits of Ilakaka (Madagascar) are similar. Where is the matrix?

The answer is simple. The matrix is gone—pummeled to oblivion—entirely disintegrated by natural weathering processes, ashes smashed to dust. In its essence, geology is one monstrous recycling program and, in the case of Tibet, the original rock was reformatted like a massive Indian hard drive being sucked under the Asian continent, with zeros written across the entire surface. Those who say matrix specimens are needed to confirm a deposit's genuine nature are simply wrong.

In early September 2011, Dr. Adolf Peretti was poring over the parcel of andesines brought back from Tibet by Richard Hughes from his 2011 visit. Piece after piece was scrutinized; some showed glassy residues, others the vivid crimson streaks that appeared to be natural copper diffusion. A bit of dirt here, a bit of color there. Exactly what you would find by examining any typical parcel of gem rough. It was getting late, but he pushed on. Huh? He noticed a dark substance on the surface of one crystal. This was not some surface residue, it didn't appear to be contamination. Could a prehistoric fragment have survived? Could it be a one… ?

The specimen was immediately dispatched to Switzerland for advanced testing. The results will be presented in Part 3 of this article. [Part 3 turned into a presentation at the 2012 Tucson show, which is summarized in this paper distributed to attendees].

The red chamber

The red chamber

A copper-red Chinese vase in Lhasa's Tibet museum. Ceramics are among the finest expressions of Chinese art and are typically made from clays such as kaolin, which itself is produced by the chemical weathering of aluminum silicate minerals such as feldspar. Red glazes such as that used on the piece above are typically made with copper. George Rossman has suggested that China's combination of a rich ceramic history involving feldspar-derived clays and copper glazes may have inspired the original ideas that one might diffuse copper into pale colored feldspars. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Getting real

Getting real

A portion of a large lot of andesine purchased in Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin) village by Richard W. Hughes on 20 August, 2011. Stones ranged in size from less than 0.25 cts to over 10 cts each. They also showed variation in transparency (from transparent to near opaque) and the colors ranged from pale orange to a rich, intense red. A small number of stones had green areas. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Peek-a-boo

Peek-a-boo

A young Tibetan girl at Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin) village. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Busload of Faith

Faith and doubt both are needed—not as antagonists, but working side by side to take us around the unknown curve. Lillian Smith

Based on the evidence first brought to light by gemologists like Masaki Furuya (2008) and Ahmadjan Abduriyim (2008), it is clear that the vast majority of transparent red feldspars that flooded world gem markets since 2002 were actually treated via copper-diffusion of an otherwise-pale feldspar. Despite cries to the contrary, testing of this material has proven that the starting material was not Mexican in origin, but from Inner Mongolia (see Appendix A).

What is truly incredible about this whole scenario is that the very gemologists who pushed to explore this subject furthest have found themselves needlessly slandered. None more so than Dr. Ahmadjan Abduriyim. In 2008, he set out to discover if there was a real andesine deposit in Tibet and, simultaneously, to confirm the validity of the Inner Mongolian deposit that JTV's "Jewel Hunter Jack" had said was used as a base material for treatment. He even went so far as to visit Xi'an to try and meet with the Chinese professor alledgedly at the root of the controversy. All this, only to find himself accused of being part of a slick and sick conspiracy.

For his trouble, Ahmadjan has had his work questioned by people who should know better (including sadly, at times, this writer).

Throughout the controversy, he showed incredible poise. Despite the withering criticism, like a Tibetan pilgrim, he was true to his faith. Om mani padme hum—the jewel is in the lotus—om mani padme hum—I know what I found—om mani padme hum—I believe—the jewel is in Tibet. Like the Tibetans themselves—despite tremendous hardships and and stupendous odds—his faith never wavered.

It's time the world apologized to Ahmadjan. Allow me to be the first. I am sorry to have ever doubted you.

|

Sapaba Speaks Are the Tibetan andesine mines real? Before answering that question, let me tell you a bit about myself. I've been in the gem trade for over 30 years, visiting and buying gem rough at countless mines around the world, particularly in Asia & Africa. Perhaps I should also mention that I sit on the Board of Desert Sun Mining, which owns the Ponderosa Sunstone mine in Oregon. Thus I've always had an interest in sunstone. Indeed I was the first who suggested to Dick Hughes that some stones might be treated. I was also the guy who introduced him to Jackie Li, a Chinese woman who came to Tucson with a bunch of rough that she said was natural and from Tibet. In July of 2011, Dick asked me if I would like to join his family on a trip to Tibet and possibly a stop at the andesine deposit he had visited the previous year. I needed no encouragement. Yes! And so we proceeded to do just that. But this time absolutely no one knew we were coming. Neither our driver nor our guide knew our plans until the last minute; indeed, even I was unsure we would be able to visit the deposit. Based on my personal observations at the site, this Tibetan andesine deposit is the real deal. If the subsequent testing confirms our field observations, I think the only question that will and should remain is how to properly separate the natural Tibetan stone from the artificially treated material. Dana Schorr |

Huh? You talkin' to me? You talkin' to me? Go find out for yourself…

Huh? You talkin' to me? You talkin' to me? Go find out for yourself…

Postscript

None of the above is an attempt to whitewash what was clearly a wrong perpetrated by a gem treater or treaters on the consumer public. As I wrote in Part I of this article in November of 2010:

…it is not to the eighteen percenters that I pen these words. Instead, it is to those whose minds are curious and open to the possibility that, despite what was likely a massive fraud committed by a professor and his son, who secretly treated feldspar and foisted it on an unwary public, there is a natural andesine mine in Tibet.

Richard Hughes, Hunting Barack Osama in Tibet

One year on, I am happy to report that the evidence is now in. Shoot out the lights. Thank you and good night.

|

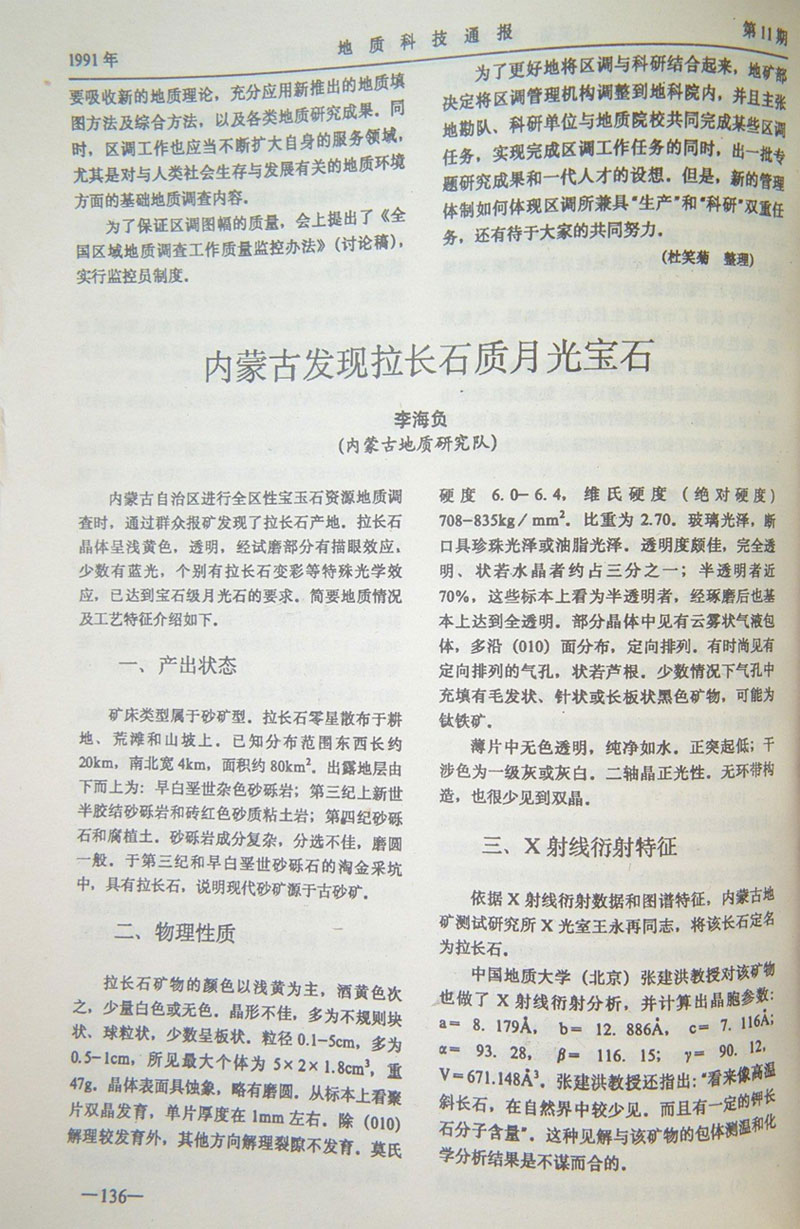

Appendix A: Inner Mongolia Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things that you didn't do than by the ones you did do. So throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover. Mark Twain If one is to treat stones en masse, a source of inexpensive treatable starting material is a requirement. In his 2008 Gems & Gemology report on the Tibetan andesine mines, gemologist Dr. Ahmadjan Abduriyim (Abduriyim, 2008) also described his visit to mines in Inner Mongolia (China) and witnessed the mining of large quantities of pale yellow andesine. This, he was told, was the starting material for the andesine treatment. Samples were collected on site, the location of which was precisely described. Abduriyim distributed samples to gemologists around the world for testing, including Dr. George Rossman (CalTech), Shane McClure, Ken Scarratt and Dr. Wuyi Wang (GIA), Dr. Adolf Peretti (GRS) and researchers in universities in Japan. Detailed descriptions of the andesines from Inner Mongolia have been published in several places in the scientific and gemological literature (see Abduriyim & Kobayashi, 2008; Dong et al., 2009; Rossman, 2009 & 2011; etc.). Detailed reports such as Abduriyim, et al. (2011) have cited no less than four further papers on the Inner Mongolian deposit. Two of these papers date from the early 1990's, long before anyone had heard of treated andesine.

Alas, one party involved in legal litigation continues to suggest there is no evidence of a plagioclase feldspar mine in Inner Mongolia, even going so far as to offer a "$1000 reward" for anyone who can send him a stone from this deposit that will match the report Abduriyim issued in 2008. This same party claims that, despite writing hither and yon and joining various Chinese associations, and despite being provided the complete deposit details in the literature, including GPS coordinates, he still cannot find confirmation of these mines. Thus he still has doubts. So allow me to paint by numbers:

You'll be home in a few days with all the answers you claim to seek. How do I know? Because I did it myself.

|

|

Appendix B: Mining in Tibet Just prior to leaving for Tibet in August 2011, the author came across the following in a book: Having been lost in thought for several minutes, he was surprised when, looking up, he found himself in open countryside. Twenty yards to the south flowed the Drichu River on its way to Dirge and beyond. In the shallows, several men were panning for gold dust. You could usually find a grain or two if you were patient. Gold wasn't mined in Tibet, of course. All mining was prohibited. To rob the earth of its belongings was considered evil but it was OK to take it from the water since the water had taken it from the earth. Drawupon, a Tibetan Khampa, in an interview with Mikel Dunham This immediately brought to mind our experience the previous year (Hughes, 2010). When we attempted to visit the Bainang locality first documented by Abduriyim in 2008, a group of angry monks emerged from their gompa and made it clear that we would be doing no such thing. We were told by the monks that the previous mining activities has upset the mountain gods and this had produced terrible weather. When we arrived in Dhongtso 5 (Zha Lin) village this year, we were told that we could go behind the village and collect stones, but we must promise not to go into the mountains and dig. Doing so, we were told, would result in lightning storms and terrible rains. Returning to my home in Hong Kong, I investigated further, discovering the following passage from Bue (1991): Although Tibetan sculptors had alternative supplies of copper to those from Nepal, it is likely that Nepalese copper continued to reach Tibet in one way or another during the 19th century for, as a rule, Tibetans themselves did not get involved in mining on a large scale. They feared upsetting the local gods of the earth, and preferred to import metals from India, China, Nepal, and East Turkestan. To that effect Hedin mentions Csoma de Körös's native source on the matter, dating from a few years before 1834: Mines are rarely excavated in Tibet. In the northern part of Nari (sic), and in Guge, some gold dust is gathered, as also in Zanskar and Beltistan (sic) it is washed from the rivers. If they knew how to work mines, they might find in many places gold, copper, iron and lead. Sven Hedin, Southern Tibet, 1922, Vol. VII, p. 185 Ordinary Tibetans have religious and economic objections to the exploitation of mines. In Tibet… …there is an old-established objection to mining on religious grounds. 'If minerals be taken out of the ground', says the ordinary Tibetan, 'the fertility of the soil will be weakened'. Many think that the minerals were put into the ground by the 'Precious Teacher', Padma Sambhava, when he brought Buddhist teachings from India, and that, if they are removed, rain will cease and the crops will be ruined. The religious objection is intensified by an economic one. When a mine is found, the local peasants and others are expected to work it without pay. This work being for the Government, the system of ula (unpaid labour) is held to apply. So the villagers have every incentive to conceal the existence of mineral wealth, and will sometimes turn out and attack those who try to exploit the mine. Charles Bell, 1928, The People of Tibet, pp. 110–111 And yet, like in all lands and cultures, contradictions abound. According to Huber (1991), there are plenty of examples of mining in Tibet. Reading this reminded me of one night we had spent in Lhasa's Muslim quarter, an area filled with butcher shops. While Buddhists are not supposed to take a life, this does not preclude them buying meat from those whose religion has no such prohibition. After all, yak tastes good and it is one of the few sources of protein in an oft-desolate land.

Mao is my co-pilot |

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank his wife, Wimon, and daughter, Billie, for joining the journey to such a remote land. Billie, bless her heart, chipped in with the great title illustration you see at the top and helped with the text, too. Isn't that awesome? Dr. Adolf Peretti contributed financial support by purchasing specimens and hours and hours of lab testing and discussions on all things andesine. Dana Schorr was ever ready to climb higher in search of adventure (but at our age, sometimes the thought is as good as the thrill). Dr. Ahmadjan Abduriyim accompanied my daughter and I to the Inner Mongolian deposits and, as always, was a wonderful travelling companion.

References & further reading

- Abduriyim, A. (2008) Gem News International: Visit to andesine mines in Tibet and Inner Mongolia. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 44, No. 4, Winter, pp. 369–371.

- Abduriyim, A. (2009) A Mine Trip to Tibet and Inner Mongolia: Gemological Study of Andesine Feldspar. GIA, News from Research. Sept. 10, 27 pp.

- Abduriyim, A. (2009) Andesine mine of Tibet [Movie].

- Abduriyim, A. (2009) The characteristics of red andesine from the Himalaya Highland, Tibet. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 31, No. 5–8, pp. 283–298.

- Abduriyim, A. and Kobayashi, T. (2008) Gem News International: Gemological properties of andesine collected in Tibet and Inner Mongolia. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 44, No. 4, Winter, pp. 371–373.

- Abduriyim, A. & Laurs, B.L. (2010) New Field Research Confirms Tibetan Andesine. GIA.edu, 1 p.

- Abduriyim, A., Laurs, B.L. et al. (2010) Andesine in Tibet: A second field study. InColor, No.15, Fall–Winter, pp. 62–63.

- Abduriyim, A., McClure, S.F., Rossman, G.R., Leelawatanasuk, T., Hughes, R.W., Laurs, B.M., Lu, R., Isatelle, F., Scarratt, K., Dubinsky, E.V., Douthit, T.R. and Emmett, J.L. (2011) Research on gem feldspar from the Shigatse region of Tibet. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 47, No. 2, pp. 167–180.

- Abduriyim, A. and Pogson, R. (2011) Separation of natural red andesine from Tibet and copper-diffused red andesine from China. GIA: News from Research, 14 pp.

- Bell, C.A. (1928) The People of Tibet. Oxford, The Clarendon press, 319 pp.

- Bue, E.L. (1991) Statuary metals in Tibet and the Himalayas: History, tradition and modern use. Bulletin of Tibetology, New Series, No. 1–3, pp. 7–41.

- Cao, Yue (2006) Study on the feldspar from Guyang County, Inner Mongolia and their color enhancement. Master's thesis, Geological University of China, Beijing, 66 pp. [in Chinese with English abstract].

- Clary, J. & Clary, B. (2008) Sunstone hunting in Tibet. Colored Stone, November.

- Dong, X.Z., Qi, L.J. & Zhong, Z.Q. (2009) Preliminary study on gemological characteristics and genesis of andesine from Guyang, Inner Mongolia. Journal of Gems and Gemmology, Vol. 11, No 1, pp. 20–24 [in Chinese with English abstract].

- Dunham, M. (2004) Buddha's Warriors: The Story of the CIA-backed Tibetan Freedom Fighters, the Chinese Invasion, and the Ultimate Fall of Tibet. New York, J.P. Tarcher, 433 pp.

- Emmett J., Douthit T. (2009) Copper diffusion in plagioclase. GIA, News from Research. 21st Aug.

- Fontaine, G.H., Hametner, K. et al. (2010) Authenticity and provenance studies of copper-bearing andesines using Cu isotope ratios and element analysis by fs-LA-MC-ICPMS and ns-LA-ICPMS. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, Vol. 398, No. 7–8, December, pp. 2915–2928.

- Fritsch, E. (2002) Gem News International: Red andesine feldspar from Congo. Gems & Gemology, Volume 38, No. 1, Spring, pp. 94–95.

- Fritsch, E., Rondeau, B. et al. (2008) Gem News International: “Red andesine” from China: Possible indication of diffusion treatment. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 44, No. 2, Summer, pp. 166–167.

- Furuya, M. (2008) Copper diffusion treatment of andesine and a new mine in Tibet. JGGL Gem Information, Vol. 37–38, pp. 1–11 [in Japanese].

- Furuya, M. and Milisenda, C. (2009) Diffusion treatment of andesine and new deposit of Tibet. International Gemological Conference, Arusha, Tanzania.

- GemResearch Swisslab (2011) Volcanic Host Rock of Tibetan Red Andesine Discovered. Press release, 22 September, Hong Kong, 1 p.

- Hedin, S.A. (1916) Southern Tibet; Discoveries in Former Times Compared with my own Researches in 1906–1908. Stockholm, Lithographic Institute of the General Staff of the Swedish Army, 11 vols.

- Hofmeister, A.M. & Rossman, G.R. (1985) Exsolution of metallic copper from Lake County labradorite. Geology, Vol. 13, No. 9, pp. 644–647.

- Huber, T. (1991) Traditional environmental protectionism in Tibet reconsidered. The Tibet Journal, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 63–77.

- Hughes, R.W. (2010) Hunting Barack Osama in Tibet: In search of the lost andesine mines. Ruby-Sapphire.com, posted 3 Nov.

- Hughes, R.W. (2011) Andesine: Timeline of a controversy. GIA: News from Research, 14 pp.

- Japan Germany Gemmological Laboratory (2008) Brief photo report from Tibet about andesine mine.

- Jewellery News Asia (2009) News & Trends: New copper isotopes method for testing copper-bearing gemstones. Jewellery News Asia, 28 September, 2009, accessed 7 October, 2011.

- Johnston, C.L., Gunter, M.E. et al. (1991) Sunstone labradorite from the Ponderosa Mine, Oregon. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 27, No. 4, Winter, pp. 220–233.

- Kratochvil, G. (2008) The Great Andesine Scam.

- Krzemnicki M.S. (2004) Red and green labradorite feldspar from Congo. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 15–23.

- Lang, D. (2002) Bickering thieves arrested after stealing professor’s data. Sanqin Daily, 29 November [in Chinese].

- Laurs B.M. (2005) Gem News International: Gem plagioclase reportedly from Tibet. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 41, No. 4, Winter, pp. 356–357.

- Laurs, B.M., Abduriyim, A. and Isatelle, F. (2011) Geology and field studies of reported andesine occurrences in the Shigatse region of Tibet. GIA: News from Research, 10 pp.

- Leadbeater, C. (2011) Tourists banned from Tibet as China draws a veil over the 60th anniversary of its rule. Daily Mail, London, 15 June, 2011; accessed 29 Sept., 2011.

- Leelawatanasuk, T. (2010) Natural Red Andesine from Tibet: Real or Rumor? Online report, Gemological Institute of Thailand, posted 3 November, 5 pp.

- Leelawatanasuk, T., Atichat, W., Wathanakul, P. and Susawee, N. (2011) SEM study of red andesine. GIA: News from Research, 4 pp.

- Li, Haifu (1991) Discovery of feldspar type moonstone gem in Inner Mongolia. Bulletin of Geological Science and Technology, Vol. 11, pp. 136–137 [in Chinese].

- Li, Haifu. (1992) First study of gem-quality Inner Mongolian labradorite moonstone. Jewellery, Vol. 1, No. 6, pp. 45–47 [in Chinese].

- Lu, R., Dubinsky, E., Douthit, T. and Emmett, J.L. (2011) Silver incorporation in Inner Mongolian and Tibetan andesine. GIA: News from Research, 9 pp.

- McClure, S.F. (2009) Observations on Identification of Treated Feldspar. GIA, News from Research, Sept. 10.

- McClure, S.F. (2011) Observations of surface residue features found on andesine from China. GIA: News from Research, 6 pp. <http://www.gia.edu/research-resources/news-from-research/surface-mcclure.pdf>

- McClure, S. & Breeding, C.M. (2009) Separation of plagioclase feldspars via chemical analysis. GIA: News from Research, Carlsbad, CA, 30 March, 2 pp.

- McClure, S.F., Rossman, G.R. and Scarratt, K. (2011) A study of andesine matrix specimens purported to be from Tibet. GIA: News from Research, 6 pp.

- Milisenda C., Furuya M. & Haeger T. (2008) A study of treated labradorite-andesine feldspars. Proceedings of the 2nd International Gem and Jewelry Conference GIT2008, pp. 283–284.

- Pei, J.-C. and Sun, C.-L. (2009) Study on gemmological characteristics of red feldspar. Journal of Gems & Gemmology, No. 3, pp. 11–14 [in Chinese with English abstract].

- Peretti, A., Bieri, W. et al. (2011) Fluid inclusions confirm authenticity of Tibetan andesine. InColor, No. 17, Summer, pp. 50–55.

- Peretti, A.,Villa, I., et al. (2011) Distinguishing natural Tibetan copper-bearing andesine from its diffusion-treated counterparts using advanced analytical methods. Contributions to Gemology, No. 10, 105 pp.

- Roskin, G. (2008a) We interrupt our Tucson Blog, Part 2. JCKOnline.com, February 12.

- Roskin, G. (2008b) Andesine update. JCKOnline.com, March 5.

- Roskin, G. (2008c) Andesine aggrevation. Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone, May.

- Roskin, G. (2008d) JCK web exclusive: The andesine report. Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone, posted November 12.

- Rossman, G. (2009) The Red Feldspar Project. California Institute of Technology, 8 pp.

- Rossman, G.R. (2011a) The Chinese red feldspar controversy: Chronology of research through July 2009. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 47, No. 1, Spring, pp. 16–30.

- Rossman, G.R. (2011b) Argon isotope studies of andesine collected during the 2010 expedition to Tibet. GIA: News from Research, 6 pp.

- Thirangoon, K. (2009) Effects of Heating and Copper Diffusion on Feldspar: An Ongoing Research. GIA, News from Research, May 29, 29 pp.

- Wang, W., Lan, Y., et al. (2010) Geological field investigation on the reported occurrence of ‘red feldspar’ in Tibet. Gems & Jewellery, Vol. 19, No. 4, Winter, pp. 44–45.

About the authors

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard's Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology.

E. Billie Hughes visited her first gem mine (in Thailand) at age two and by age four had visited all three major sapphire localities in Montana. A 2011 graduate of UCLA, she qualified as a Fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA) in 2013. Since that time, she has distinguished herself with her photographic work published in Terra Spinel, the Wall Street Journal, Ruby & Sapphire: A Collector's Guide and Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide, along with many periodicals such as Gems & Gemology. Billie has visited scores of countries for research on gems, including the US, Asia, Africa and even Greenland, and has delivered lectures in around the world. She is a talented photomicrographer and a three-time winner of the Gem-A's annual photographic competition. Some of her latest work can be found in Inside Out: GEM•ology Through Lotus-Colored Glasses.

Wimon Manorotkul joined the gem trade in 1979. She qualified as an FGA (with distinction) in 1984. A skilled gemologist and photographer, her gem and inclusion photographs have graced numerous industry publications. Some of her latest work can be found in Inside Out: GEM•ology Through Lotus-Colored Glasses.

Dana Schorr of Schorr Marketing was a Santa Barbara (CA)-based gem dealer and gold trader with three decades of experience in the business. He sat on the Board of Oregon's Desert Sun Mining & Gems, which owns the Ponderosa sunstone mine, and passed away in August 2015.

Notes

A slightly abridged version of this article was first published in The Guide (November/December 2011, Vol. 30, No. 6, pp. 1, 4–9, 13).

This article is the second in Richard Hughes' study of the Tibetan andesine mines. He has written a number of papers on andesine, as follows: