Ruby & Sapphire • Judging Quality, Prices, Part 4

Notable red spinels

Among the most famous titled rubies, most are not rubies at all, but red spinels. Two important examples are found in the United Kingdom: the Timur Ruby, and the most famous of all, the Black Prince's Ruby. Despite the fact that these are actually red spinels, their colorful tales are worth telling.

Black Prince's Ruby

Few precious stones have such a long and storied history as this large, semi-polished, crimson orb. The following is based largely on Orpen (1890), Younghusband & Davenport (1919) and Sitwell (1953).

Although the gem was probably mined at Badakshan's famous balas ruby mines along the Afghanistan border, the gem's first documented appearance is in fourteenth-century Spain. At that time, Spain was ruled by a number of petty kings, one of whom was a Moorish prince, Mohammad, of Granada. Don Pedro the Cruel ruled nearby Seville, and it was to him that Mohammed fled after being deposed by his brother-in-law, Abu Said. Don Pedro's army eventually brought Abu Said to heel. When they arrived to negotiate, Abu Said and his attendants were killed, and their jewels seized. The date was 1366. Among the jewels was a large red spinel octahedron, the size of an egg. It is today known as the Black Prince's Ruby.

Don Pedro soon found it his turn to flee, his adversary being none other than his own brother, Henry. In 1366, he fled to Bordeaux, where the Black Prince [14] kept court. Don Pedro beseeched the Black Prince to help, promising untold treasures in return. Henry was duly defeated and the large red stone passed as payment to the Black Prince, in 1367.

Figure 10.17a: Britain's Imperial State Crown contains more famous gems than virtually any other ornament in the world. These include the Black Prince's Ruby (see Fig. 10.18)…

10.17b: …the Stuart Sapphire…

10.17c: …and St. Edward's Sapphire. (Photos: HMSO, London)

The gem reappeared in the hands of the English king, Henry V, at Agincourt, on Oct. 25, 1415. The gallant king, with his army reduced to 15,000 men, was falling back upon Calais when at Agincourt he encountered Duc d'Alençon, the French prince, and his army of 50,000 men. The morning of the climactic battle Henry appeared dressed in most splendid attire, with gilt armor. Upon his helmet was a crown garnished with rubies, sapphires and pearls, including the Black Prince's Ruby.

Henry's helmet was more than mere decoration, for on that day he was set upon by the French prince, Duc d'Alençon. The Frenchman struck his helmet a mighty blow with his battle axe, nearly killing Henry. Others also attacked him, even managing to break away a portion of the crown. Miraculously, though, both the stone and Henry survived. After the battle, a French prisoner retrieved the broken fragment and brought it back to England, an act for which he was duly reimprisoned. The identical helmet worn by Henry at Avincourt is said to reside in Westminster Abbey, shorn of its jewels. Two deep gashes are readily visible, bearing mute testimony to the gallantry of Henry V on that fateful day. [15]

From here the precious gem passed through the hands of numerous British kings, including Henry VIII and his daughter, Elizabeth I, who kept it in her private collection. She did show it to a Scottish envoy, Sir James Melville, however. One evening the Queen took him into her bedchamber, where "she shewed me a fair ruby, great like a racket-ball. I desired she would either send it to my queen [Mary, Queen of Scots] or the Earl of Leicester's picture. She replied 'If Queen Mary would follow her counsels she would get them both in time and all she had, but she would send a diamond as a token by me.'" It was for the Black Prince's Ruby that the envoy begged, but Mary was destined to get neither.

King James I had the stone set in his state-crown, for the Earl of Dorset describes the stone in an inventory of the crown jewels. His description of the imperial crown concludes: "and uppon the topp a very greate ballace [balas ruby, or spinel] perced." We know this to be our stone for at some point in time it had been drilled ('perced') at the top with a small hole, so as to be worn suspended from the neck, a common occurrence with oriental gems. Today this hole is capped with a small ruby.

After the coronation of Charles I, by a fortunate occurrence, the great gem was not placed in the jewel house along with the other royal treasures. If it had it would have been lost, for when Cromwell took power and Charles I was executed, all the treasures found there were either melted down or sold by order of the Commonwealth. Among the priceless pieces thus lost was the gold filigree crown of Edward the Confessor, which was broken up and sold for its weight of bullion. Orpen (1890) remarked… "Such vandalism is almost enough to make one a Jacobite."

But the Black Prince's Ruby was not among them. According to the Parliamentary sales list of Charles I's Crown Jewels, there is an entry recording the sale, for £4, of a 'perced balas ruby wrapt in paper by itself,' which several authors have identified as the Black Prince's Ruby. Sitwell (1953) believes that this is incorrect, and that the Black Prince's Ruby is more likely to have been that identified as the Rock Ruby, which sold for £15.

In any event, in 1660 it was bought by an unknown party, who resold it to Charles II after the restoration of the Stuarts (Michael, 1983). During the reign of Charles II, the stone, by now set in Charles II's State Crown, had another narrow escape. It was nearly stolen by the notorious Colonel Blood, who, unbelievably, was later pardoned by the King.

Once again, in 1841, the crown was almost lost, this time by fire. Only the quick actions of police inspector Pierse saved the day. As the Tower burned, Pierse broke through the iron bars with a crowbar to rescue these irreplaceable objects. Again, during World War II, the royal regalia was once more in danger, this time from Hitler's bombers. However, they survived undamaged and today the giant Black Prince's Ruby can be viewed in all its glory in the Tower of London, along with the rest of the English Crown Jewels.

Figure 10.18 Perhaps the world's most famous ruby, the Black Prince's Ruby, is actually a large red spinel. Its history is documented back to 1366 AD. Today it is mounted on the front of England's Imperial State Crown, which is located in the Tower of London. (Photo: HMSO, London)

The Black Prince's Ruby is now mounted in the front of the Imperial State Crown, just above the famous Cullinan II Diamond. It is a huge, semi-polished octahedron. [16] Sitwell (1953) states that the stone is backed by a gold foil, as were many ancient gems, to improve its brilliance. This has not been removed for fear of damaging the gem. The stone measures some two inches (5.08 cm) in length and is of proportionate width (Younghusband, 1919). Its exact weight is unknown, but estimates put it at ~170 ct. As earlier stated, it is drilled at one end and a small ruby is set atop the opening.

According to Younghusband (1919), "the question is often asked: 'What is the value of this stone?' And the answer may safely be given that it is priceless, for no amount of money can buy it." It is indeed the most famous gemstone in the world's most famous gem collection.

Timur Ruby (Khiraj-i-alam, or 'Tribute to the World')

The Timur Ruby is a large red spinel and rests today in the private collection of the British monarch, mounted on a gold chain along with three other "Indian rubies." It is a large, tabular, semi-polished stone of 361 ct which carries Persian inscriptions in Arabic script. Inscriptions give the names of previous owners, as follows (Twining, 1960):

| Ruler | Hirja year | Christian year (AD) | Reigned |

| Akbar Shah | 1021 | 1612 | 1556–1605 |

| Jehangir Shah | - | - | 1605–1627 |

| Sahib Qiran Sani (Shah Jahan) | 1038 | 1628 | 1628–1658 |

| Alamgir Shah | 1070 | 1659 | 1658–1707 |

| Badshah Ghazi Mahamad Farukh Siyar | 1125 | 1713 | 1713–1718 |

| Ahmed Shah Duri-i-Duran | 1168 | 1754 | 1748–1772 |

The Timur Ruby is said to have passed into Timur's hands when he sacked Delhi in 1398. The great Tartar conqueror stayed in India for little over a year, returning to Samarkand with all his booty. Upon his death, the ruby went to his son, Mir Shah Rukh, and in due time to his son and successor, Mirza Ulugli Beg. By this time the Tartar empire was on the wane and during one of the wars between the Tartars and Persians, the ruby came into the hands of Shah Abbas I of Persia. Shah Abbas presented the ruby to his close friend, Jahangir, the Mughal Emperor of India, in 1612. At that time, the gem had the names of Timur's son and grandson, and Shah Abbas himself, engraved upon it, but these inscriptions no longer exist. It is unknown whether they were obliterated over the course of time, or at the behest of Jahangir. In any event, after taking possession of the ruby, Jahangir had his own name engraved upon it, as well as that of his father, Akbar. When his favorite wife, Nur Jahan, chided him for defacing such a magnificent gem, he replied: "This jewel will more certainly hand down my name to posterity than any written history. The House of Timur may fall, but as long as there is a King, this jewel will be his."

Upon Jahangir's death, the Timur Ruby passed to his son, Shah Jahan (of Taj Mahal fame), who also had his name inscribed on it, and placed it in the famed Peacock Throne. Shah Jahan's son, Aurangzeb (Alamgir Shah), seized control of both the throne and ruby, and added his own name to the inscriptions. The last of the Delhi emperors to inscribe his name upon the gem was Mahomed Farukh Siyar. His successor, Nadir Shah, invaded India and sacked Delhi in 1739. The royal loot carried away to Isfahan included both the Koh-i-Nur Diamond and the Timur Ruby, as evidenced by the following inscription on the Timur Ruby:

This (is) the ruby from among the 25,000 genuine jewels of the King of Kings, the Sultan Sahib Qiran [Timur], which in the year 1153 [1740 AD] from the (collection of) jewels of Hindustan reached this place [Isfahan].

The jewel's last inscription is that of Ahmad Shah, commonly known as Abdali or Durani, who at the time of Nadir Shah's assassination in 1747 held an important command in his army. Upon hearing of the murder, he attempted to seize the throne, but succeeded in securing only a large amount of booty. This he took with him when he marched south at the head of his Usbeg troops and founded the kingdom of Afghanistan. On his death in 1772, his son, Timur Shah, ascended the Kabul throne, and the ruby eventually passed to the latter's youngest son, Shah Suja. When expelled by Dost Mahomed, he took refuge in the Punjab, where Ranjit Singh, 'Lion of the Punjab,' forced him to surrender both the Koh-i-Nur and the Timur Ruby.

|

A study in primitive life forms What is the difference between a taxidermist and a tax collector? Mark Twain, Mark Twain's Notebook, Chapter XXXIII THERE is a particular type of single-cell organism which goes by the name of the government bureaucrat [bureaucratius simplicius]. To scientists, it is most easily characterized by its lack of even elementary reasoning, along with a strong desire to possess what is yours. They bear a certain resemblance to other primitive parasites, such as the politician and lawyer. Indeed, they may be related. What with the rapid pace of change today, it is easy to conclude that such vermin are a modern phenomenon. But this is not the case, as evidenced by the following tale of a fifteenth-century ruby trader who had occasion to visit Sumatra shortly after his companion had died: As soon as our merchandize was landed this chief raised a quibble, asserting that, as my companion was dead, all the said merchandize came to him [the chief], and that he would have it… He thereupon ordered all my property to be seized, and caused all my person to be searched. There were found upon me rubies of the value of three hundred ducats, which I had bought [in Pegu]. These they took, and the chief appropriated them to himself. Journey of Hieronimo di Santo Stefano, ca. 1496 (from Major, 1857) While extermination has proven impossible, businesspeople have developed certain evasion techniques. One was related to me by a European trader. He told of having to swallow a parcel of particularly valuable emeralds when forced to transit a land where one variety, the customs agentus, was known to be endemic. The ruse succeeded, but this created an additional conundrum. Upon arriving at his final destination, his customer was eager to view the gems. Sadly, he had to be told that there would be a delay, for the gems were still being… er… cleared. |

In the end, Jahangir's prediction was born out. When the British East India Company annexed the Punjab in 1849, they also annexed the Koh-i-Nur Diamond and Timur Ruby. Both were later presented to Queen Victoria. Despite the occasional protests from India, it is in the British Monarch's hands that they remain (Times of London, 1912; Twining, 1960).

Catherine the Great's Ruby

This is the second-largest red spinel of quality on record, at 414.30 ct (or 398.72 ct according to the USSR Diamond Fund, 1972) and is housed in Russia's Kremlin (see box, page 282 for a full description).

A case of mistaken identity

Red spinel is not the only ruby look-alike found in Burma's Mogok Stone Tract. Red tourmaline (rubellite) is also common. This may be the origin of the famous red gem found in Russia's Diamond Fund. The 255 ct "great ruby" was once among the jewels in the imperial treasure in Prague, and was removed by troops under H.C. von Königsmarck in 1648, during the sack of that city in the Thirty Years War. It was later sent to Sweden and, in 1777, presented to Catherine II of Russia by Gustaf III. When examined by A.E. Fersman during his inventory of the Czarist treasure in 1925, he found it to be a pink tourmaline of no particular value or merit. In appearance, it resembles a bunch of grapes (Zenzén, 1930; Fersman, 1947; USSR Diamond Fund, 1972).

Famous titled red spinels are summarized in Table 10.4.

Rubies, spinels & sapphires in the Mughal treasury

No one collected gems like India's Mughals, who lorded over many parts of that land from 1526–1707. A detailed analysis of their treasury has been given by the great Mughal specialist, Abdul Aziz (1942), summarized in Table 10.5.

Famous blue sapphires

Smithsonian

Although large rubies of quality are extremely rare, fine examples of large sapphires are relatively less so. Over the centuries, Sri Lanka has produced more giant sapphires of gem quality than any other source. Several fine examples are found in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC.

Bismarck Sapphire. The Bismarck Sapphire, weighing in at 98.6 ct, is a faceted gem of Sri Lankan origin donated by Countess Mona Bismarck (Dunn, 1975).

Logan Sapphire. This is the largest sapphire in the Smithsonian collection, a giant of 423 ct, set with 20 diamonds. The stone has a rich blue color but unfortunately is faceted with a large window. It was donated by Mrs. John A. Logan and is considered to be one of the finest large sapphires in existence.

Star of Artaban. Also in the Smithsonian collection is the Star of Artaban, a blue six-rayed star sapphire of 316 ct. It is said to be of Sri Lankan origin (Punchiappuhamy, 1984).

Star of Asia. This, too, is in the Smithsonian collection. An extraordinary 330 ct of the richest blue-violet color, it is one of the finest star sapphires in existence.

Star of Bombay. The Star of Bombay was bequeathed to the Smithsonian by the famous silent movie actress, Mary Pickford. It weighs 182 ct and is a beautiful blue-violet star (White, 1991).

American Museum of Natural History

Star of India. In New York, at the American Museum of Natural History, is found a fine collection of Sri Lankan sapphires, particularly stars. Largest of these is the Star of India, weighing a massive 563.35 ct. This stone is actually of Sri Lankan origin and shows a fine star, although the color is a rather grayish blue. According to Sofianides & Harlow (1990):

The huge 563-carat Star of India sapphire is one of the [J.P.] Morgan gifts. Its name suggests a story – one might speculate that, after being mined in Sri Lanka in the sixteenth century, it circulated among the treasures of Indian potentates…. George F. Kunz [1913a] recorded only this enigmatic statement: "[It] has a more or less indefinite historic record of some three centuries…." How the gem came into Kunz's hands is unrecorded, but rumor has it that a royal owner needed cash without publicity. An alternate, but doubtful, story is that Kunz had the stone fashioned in New York City in 1900 – so much for romance! No matter, the Star of India is magnificent.

A.S. Sofianides and G.E. Harlow, 1990

Midnight Star. Another large star in this collection is the Midnight Star, a deep violet Ceylon stone of 116.75 ct. (Sofianides & Harlow, 1990).

Figure 10.19 The Midnight Star, weighing 116.75 ct. (Photo: Harold & Erica Van Pelt/American Museum of Natural History)

British Crown Jewels

Stuart Sapphire. The early history of the Stuart Sapphire is somewhat obscure, although it most probably belonged to Charles II, and was certainly among the jewels which James II took with him when he fled to France. From him it passed to his son, Charles Edward, the Old Pretender, who gave it to his son Henry Bentinck, later known as Cardinal York. As the Stuart cause was then dead, he left the sapphire with other Stuart relics to George III.

In Queen Victoria's State Crown this sapphire occupied a prominent position just below the Black Prince's Ruby. It was later replaced by the Second Star of Africa (Cullinan II) diamond, and today is set in a similar position on the opposite side of the same crown.

The Stuart Sapphire is more of historical than real value. Although of a fine blue color, it contains one or two blemishes and is drilled at one end, probably so that it could be worn as a pendant, as was common in earlier times. It is oval in shape, about one and a half inches in length by one inch in width, and is set in a gold brooch (Younghusband & Davenport, 1919).

St. Edward's Sapphire. St. Edward's Sapphire is now set in the center of the cross-patee on top of the same crown as the Stuart Sapphire. It is a stone with a history stretching back farther perhaps than even the Black Prince's Ruby. According to tradition, the St. Edward's Sapphire was originally set in the coronation ring of Edward the Confessor, who was crowned in 1042 AD. Special powers were ascribed to this sapphire, including those of curing cramps.

St. Edward's Sapphire is today a rose-cut gem, but this was probably not the original style, and it is thought that recutting was performed during the reign of Charles II. It is a stone not only of exceptional color and brilliance, but also with a marvelous legend behind it. The legend states that Edward the Confessor greatly admired St. John the Evangelist. One morning he happened to meet a beggar near Westminster. Having previously given away all his money, he presented his ring to the beggar. Some time later two Englishmen on pilgrimage to the holy land ran into a storm in Syria. Suddenly the path ahead lit up and an old man approached, preceded by two youths bearing candles. On hearing that the pilgrims were English and that Edward was their King, the old man guided them to an inn, where he found them food and lodging. The next morning as they were leaving, he told them he was John the Evangelist and gave them the ring to return to Edward. Bidding them goodbye, John said that he would see Edward in paradise in six months time. The pilgrims eventually returned to England, where they gave the ring and message to Edward. Edward recognized the ring, and thus began preparations for his death. Dying six months later, he was buried at Westminster with the ring on his finger. According to legend, the tomb was later opened in the twelfth century and the ring given to the reigning King (Sitwell, 1953).

Muséum National D'Histoire Naturelle

Ruspoli's Sapphire ('Wooden Spoon-Seller's Sapphire' or 'Great Sapphire of Louis XIV'). E.W. Streeter, in his book Precious Stones and Gems (1892), describes a number of fine sapphires. One of these was in the collection of the Musée au Jardin des Plantes, in Paris, and weighed 133.06 ct. The same stone was also described by Sourindro Mohun Tagore in his classic, Mani-Málá (1879, 1881), referring to it as the Wooden Spoon-Seller's Sapphire, in reference to the poor man who is said to have found it in Bengal, India. Streeter said it was without flaw. This is undoubtedly the same stone that resides today in Paris's Muséum National D'Histoire Naturelle, for it is of a distinctive lozenge shape and possesses only six facets, appearing like a huge sapphire rhomb. It is indeed nearly "without flaw," containing only one small feather and crystal inclusion, and is possibly of Burmese or Sri Lankan origin.

Figure 10.20 The 135.8-ct Ruspoli Sapphire (Wooden Spoon Seller's Sapphire), in Paris' Musée au Jardin des Plantes. (Photo: H.-J. Schubnel, Galeria de Minéralogie, Muséum National D'Histoire Naturelle)

According to the Museum's H-J. Schubnel (pers. comm., 16 Dec.–5 Jan., 1994–5), its true weight is 135.8 ct. In the museum it is known as Ruspoli's Sapphire. During the 17th century, a Roman prince named Ruspoli sold this sapphire to a salesman, who, in turn, sold it to King Louis XIV sometime before 1691. At that time it was the third most prominent gem in the French Crown Jewels.

During the French Revolution, the royal gems were confiscated by the revolutionary government and then stolen by Cadet Guyot. Only a few escaped, including the Ruspoli jewel, probably saved by its peculiar form. In 1796, the revolutionary government allowed the Museum to choose a few gems for educational purposes. Daubenton, the Museum's director, chose the Ruspoli Sapphire, cleverly labelling it as a sapphire crystal. Obviously he was lying, but it was for a noble cause. Today the Ruspoli Sapphire can be viewed in the Muséum National D'Histoire Naturelle (see Figure 10.20). [17]

State Gem Corporation of Sri Lanka

Probably the finest large star sapphire in existence is the 393-ct piece owned by the State Gem Corporation of Sri Lanka. It is an incredibly rich blue color, much finer than the Star of Asia, and also exhibits a beautiful star. In 1981, this gem went on exhibition at the Festival of Sri Lanka in the Commonwealth Institute, Kensington, England, guarded by a 4.5-foot (137 cm) cobra sentry (Daily Telegraph, 1981).

Other notable sapphires

Catherine the Great's Sapphire. This colossus weighs in at a massive 337 ct. Of unknown origin, it was presented to Catherine II ('the Great') of Russia [b. 1729; d. 1796] in the latter part of the 18th century, by an unidentified admirer. The stone remained part of the Romanoff jewels for more than a century and a half, until sold by Nicholas II to finance a hospital train for the Russian army during World War I. It finally ended up in the US, where it was purchased by Harry Winston for an undisclosed sum. Winston placed the gem in his "Court of Jewels" collection, which toured the US from 1949 to 1953. It was later sold to an unknown buyer (Anonymous, 1951b; Krashes, 1986).

Gem of the Jungle. Next to the velvet-blue sapphires of Kashmir, those from Mogok are the finest. One fabulous 598-ct piece of Mogok rough was purchased by the English dealer and lapidary, Albert Ramsay, in 1928. This fine stone was found near Gwebin, by a miner named U Kyauk Lon (U Hla Win, pers. comm., May 2, 1994). $13,000 was paid for the rough, which came to be known as the Gem of the Jungle. Nine different stones were cut from it, ranging from 66.53 to 4.39 ct, and including stones of 20.11, 19.19, 13.15, 12.29, 11.39, 11.18, and 5.57 ct. All were personally cut by Ramsay and were said to be of exceptional color. A marvelous account of the purchase and cutting of this gem is given by Ramsay & Sparkes (1934).

Parure of Queen Marie Antoinette. This is a seven-piece jewelry set containing approximately 29 sapphires, of which 18 are stones of perhaps 20 ct or more. During the French Revolution they vanished, but later reappeared, to be bought by Napoleon, who gave it to his wife, the future Empress Josephine. Upon her death, it went to her daughter, Queen Hortense, who, after the fall of the Bonapartes, sold it to Louis- Philipe, then Duke of Orleans. Since then it has been worn by wives of the successive heads of the House of France, and now belongs to the Count of Paris. Three separate dynasties that have ruled France have owned it: the Bourbons, the Bonapartes, and the Orleans. A fine illustration of the parure is given in Michael (1983). Although most possess large windows due to overly shallow pavilions, together they are magnificent.

|

World's largest? Among the most difficult tasks facing the gemologist is that of testing the world's largest. 'Tis not a task for the meek; those called upon to test the world's largest somesuch are rarely showered with trust. All specimens are "priceless" and all are "absolutely genuine," having been either family heirlooms dating from Timur's sacking of Delhi in 1398 AD, or recently unearthed from someone's backyard or rice paddy. Thus the owner often demands to watch the proceedings, fearing that, if their back is turned for even an instant, the vulpine tester will slide an identical specimen out from under his cloak for the switch. During the author's many years practicing gemology, people constantly turned up with the "world's largest" this or that. I've been privileged to examine the "world's largest ruby" (a large chunk of battered red glass), the "world's largest imperial green jade" (a large chunk of translucent green glass) and the "world's largest sapphire" (a large chunk of battered blue glass). But perhaps most impressive of all was the "world's largest pearl." So large was this that a fruit scale had to be used to determine its weight. Indeed, it was a pearl of sorts, but, to be frank, that may be an abuse of the term. It actually resembled something extruded from the rear of an enormous oyster, perhaps shortly after a meal of tainted shellfish. No doubt this extraordinary specimen now rests, yoke-like, between the pendulous breasts of a society maiden on the wrong side of 40. While owners of such gems may genuinely believe them to be priceless, they surface most often from the bowels of unscrupulous dealers' collections, always with an inflated appraisal claiming them to be more valuable than the British Crown Jewels. This was the case with the infamous Life and Pride of America Star Sapphire, which featured in many news reports of 1985 and 1986 (Hughes, 1987b). In a story that would warm the heart of even the most jaded observer, one Roy Whetstine claimed to have bought the 1905-ct stone for $10 at the Tucson gem show. But things turned dour when a reporter discovered that one L.A. Ward of San Diego, who appraised it at the whopping price of $1200/ct, had appraised another stone of the exact same weight several years before Whetstine said he found it. Photographs of the "gem" revealed an opaque corundum lump that would be put to better use dressing grinding wheels than windows at Tiffany. |

Another fine sapphire necklace is pictured in Michael's book; it is the 108-sapphire and diamond necklace of Queen Maria Christina of Spain. Originally from Sicily, she was the wife of Ferdinand VII, her mother's brother. After a terrible civil war, she fell in love with a bodyguard. The scandal of their marriage forced her to leave Spain. She had her portrait painted wearing this beautiful necklace. The jewel was sold by Christie's in 1982 for $297,000 (Michael, 1983).

During the London Exhibition of 1862, two magnificent sapphires were on display (Streeter, 1892). The larger, an oval of somewhat inky color and free from defect, weighed about 252 ct, and was cut in 1840. Although smaller at 165 ct, the second stone was of finer color. According to Streeter, it was by far the finest sapphire of its time to appear in Europe.

Streeter also mentions a fine sapphire in the famous Hope Collection, but no weight was given. It was noted because the gem retained its beauty as well by candle as by daylight. Another, in the Orleans Collection, was called in Madame de Genlis' tale Le Saphir Merveilleux (Streeter, 1892). It was violet by candlelight, but blue by daylight.

S.M. Tagore, in his classic work, Mani-Málá (1879), describes several celebrated sapphires. One of these was a fabulous stone of 951 ct, and was seen by an English ambassador to the Court of Ava (Burma). Tagore also mentions a curious custom among the Hindus of India. They were said to have a prejudice against sapphires, believing the blue gem to be the bringer of misfortune.

In consequence of this notion, some of them would invariably keep a stone on trial for several days before they would make final settlement with the sellers. Hence, perhaps, the paucity in the numbers of Sapphires in their possession.

S.M. Tagore, 1879, Mani-Málá

Famous blue sapphires are summarized in Table 10.6.

Famous fancy sapphires

Few fancy sapphires are described in the literature although there exist many fine examples, particularly from Sri Lanka. Australia, being an English-speaking country, has several well-documented examples.

Anderson's (Willows) Yellow. This was a 21-gram golden yellow stone found on the Willows field in Queensland in 1949. It produced a cut stone of 70 ct, later cut into several smaller gems, the largest weighing 35.75 ct.

Golden Willow (Golden Queen). In 1951, the Willows field again turned up a large yellow. This was named the Golden Willow, renamed the Golden Queen, and weighed 322 ct in the rough. It produced a 91.35-ct cut stone. The Willows field is noted for large yellow sapphires and a number of yellow-green gems in the 50–100 ct range have been found there.

Queensland. Queensland is famous for producing large black star sapphires. The best known is the Queensland, a 1156-ct cabochon giant. Although the inexperienced may believe such a stone to be extremely valuable, this is not the case, for these huge stones are typically heavily included. Their value is chiefly as curiosity items, rather than as true gems.

Although a number of large yellow sapphires have come from Australia, this is not the only source. The author has had the pleasure of examining one of the largest yellow sapphires from Thailand. It was a large emerald cut stone of approximately 75 ct, and owned by a Thai dealer. The stone was too shallow, possessing a rather large window, but in all other ways was magnificent. It was of the preferred Mekong Whisky yellow-orange color and without flaw.

In the American Museum of Natural History is what many consider to be the world's largest fine padparadscha. It is an oval stone of 100 ct (Sofianides & Harlow, 1990).

Notable examples of fancy sapphires are summarized in Table 10.7.

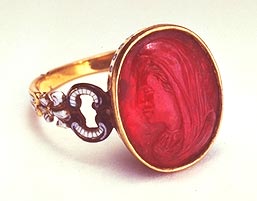

Figure 10.21 Engraved rubies of quality are extremely rare. The above is from France, ca. 1700 AD. (Photo: British Museum)

Engraved & carved rubies and sapphires

Due to its great hardness, only a few examples of carved/engraved corundums have come down to us from ancient times. Engraved gems were formerly of much greater importance than at present. Numerous books devoted to these magnificent works of art have been written, particularly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Undoubtedly the most prolific of the authors on this subject was C.W. King.

Writing in the late nineteenth century, King authored a number of books on the glyptic arts. In his Natural History, Ancient and Modern, of Precious Stones and Gems, and of the Precious Metals (1865), he describes several examples of both ruby and sapphire which have been engraved, mostly in Roman times:

…the experienced Lessing (A. Br. lxxix.), and later the Count de Clarac (Cat. des Artistes Gr. et Rom.), altogether deny the existence of any really antique intagli in these harder gems; …Nevertheless, a few works in Ruby of apparently indisputable antiquity have been observed by me amongst the thousands of other gems examined. First, on account of the quality – a large oval slightly convex stone, of the true "pigeon's blood" tint, and weighing apparently about 3 carats – is one in the Devonshire Parure (No. 17 in the Bandeau), engraved with a Venus Victrix – a but poor intaglio in the latest Roman manner.

C.W. King, 1865

Figure 10.22 This Burmese sapphire Buddha carving, housed in the British Museum, is a rare example of a quality carved sapphire. Due to the lack of royal patrons, modern artisans seldom have an opportunity to sculpt with such fine material. (Photo: © Fred Ward)

King goes on to mention several other engravings done in spinel, but the general impression is that truly ancient intagli done in ruby were decidedly scarce.

Ancient sapphire (hyacinthus) engravings were only slightly less scarce. Like ruby, on account of the extreme hardness the ancients mostly employed sapphire as a mere ornamental stone for setting in their jewelry, drilled and semi-polished, but otherwise unengraved and unshaped.

Amongst the Rutupine antiquities preserved in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge, a portion of a necklace of small rough Sapphires drilled at each end and linked together with gold wire, the exact ornament referred to by the poet Naumachius.

Previous to the Imperial [Roman] epoch, engravings in Sapphire are of the rarest possible occurrence. A small Etruscan scarab, however, on an inferior variety has recently come under my notice, and also a magnificent head of jupiter inscribed IIY, executed in the purest Greek style. This latter had been discovered as ornamenting the pommel of a Turkish dagger, the intaglio turned downwards, and the back of the stone rudely facetted by the Oriental lapidary into whose hands this precious monument had fallen, an additional proof of its genuine antiquity. This stone was one inch in diameter.

C.W. King, 1865

Superior to this as a work of art, and belonging to the same school, was the nearly full face of the Medusa's Head, described by King as one of the chief glories of the famous Marlborough Collection. The carving was said to have been enhanced by the material's fine quality. Most famous, though, was the Signet of Constantius II (then in the Rinuccini Collection), on a perfect stone weighing fifty-three carats. The Emperor is represented as spearing a monstrous wild boar, designated thereon [the Greek characters xi-iota-phi-iota-alpha-omicron] (from his sword-like tusks), before a reclining female figure personifying "Cæsarea of Cappadocia," the scene of the exploit. The inscription CONSTANTIVS AVG in the field suggests that this costly stone had been engraved for the actual signet of the imperial hunter. Also mentioned by King was a fine sapphire engraving of Hebe feeding the Eagle. The stone, heartshaped and of fine color, measured 1.5 x 1.25 in (3.81 x 3.175 cm), and apparently belonged to the time of Hadrian.

Modern engraved sapphires were also described by King:

Of modern works, the finest ever done is the portrait of Pope Paul III., ascribed, no doubt with justice, to the famous Alessandro Cesati, in the Pulsky Collection. It is a beautiful Sapphire 0.75 inch [1.9 cm] square, a truly inestimable gem, both for its fine quality and the spirit and life of the engraving, and was certainly the signet of the Pontiff himself. Inferior to this in point of art was the bust of Henri IV. by Caldoré (with his initials) on a large octagonal stone of pale colour, but possessing great historical interest. A large number of pale Sapphires may be seen in cabinets, engraved with heads of figures, usually but poorly done, in the style of the Cinque-cento. The reason is explained by De Laet (i. 7): – "The sort which is pale, or watery, is painted on the back with indigo, so as to imitate the sky-blue and superior kind, although this method is forbidden to jewellers to employ unless there be something engraved upon the stone, in order that its quality may distinguished.

C.W. King, 1865

Famous engraved rubies and sapphires are summarized in Table 10.8.

Figure 10.23 This 12.6-kg sapphire giant from Burma is owned by Myanma Gems Enterprise, the Rangoon government gem monopoly. In order to see if something of gem quality might be lurking within, MGE staff disemboweled it with drill and saw. Alas, the interior was just as opaque as the skin. (Photos: U Khin Mg Win/U Hla Win)

Rough corundum giants

Among the largest pieces of rough sapphire ever reported was that found in approximately 1967, at Mogok, Burma (Anonymous, 1967). It was bluish gray in color, measured 27 inches (68.58 cm) across and weighed a massive 63,000 ct (12.6 kg). The Myanma Gems Enterprise., a state-owned concern is the owner of this giant sapphire crystal. But even this is dwarfed by some of the giant crystals unearthed in Sri Lanka. One doubly-terminated specimen tipped the scales at 40.3 kg. Such large crystals are generally not of gem quality. They are summarized in Table 10.9.

Chapter 10 continues with…

Of related interest, see also Burmese Sapphire Giants, adapted from Ruby & Sapphire.

Notes

14. The Black Prince was Edward, Prince of Wales [1330–1376]. His epithet "Black Prince" may reflect the terror he inspired in the French, but it probably referred to the color of his armor. [ return to text ]

15. As well as the lack of properly sharpened battle axes among the French at Avincourt. [ return to text ]

16. Prior to the end of the eighteenth century, eastern lapidaries rarely faceted the precious stones on which they worked (Meen & Tushingham, 1968) [ return to text ]

17. Bank (1973, p. 125) gives a slightly different version. He puts the sapphire at 135.20 ct (or 132-1/16 ct). It was supposedly acquired by the Rome's House of Rospoli [sic?], and sold to a German Prince, who, in turn sold it to the French jeweler, Perrer, for 170,000 francs. Morel (1988) states that it was valued at 100,000 livres during the inventory of 1791. [ return to text ]

Please note: This section of Chapter 10 omits the sidebar "Maharajahs: India's fantastic fetish princes" not to keep the Information Superhighway safe for children in the provinces but rather because it may already be found in the web version of the India section of Chapter 12, World Sources.