The Burma Ruby Mines, Ltd.

The Times of London published the prospectus for the company on Feb. 27, 1889. That morning, extraordinary scenes were witnessed at the company's offices, as the following extract shows:

If St. Swithin's Lane had been a ruby mine itself the scene witnessed there yesterday morning could not have been more remarkable. The crowd around New Court was so dense that Lord Rothschild and other members of the house were unable to get in by the door. So a ladder had to be got, and the spectacle was seen of a number of great financiers entering their own office in a burglarious fashion. The clerks had to be smuggled in by a back entrance behind the Mansion House. The surging crowd in front drove a telegraph boy right through the window of a baker's shop opposite, the poor fellow being rather severely hurt. The fortunate possessors of Ruby Mine application forms, which were being hawked at five shillings, had to pass between files of policemen to hand in their applications. The next time the Messrs. Rothschild make an issue, it would be well for the police to arrive on the scene before the stags.

Financial News, London, Feb. 28, 1889

Within hours, the issue sold out. General public and company directors alike were under the mistaken impression that fabulous riches were just waiting to be unearthed in Mogok. No one gave a thought to the difficulties of mining gems in such an inhospitable and remote location. Instead, they could see but one thing--rubies--pigeon's blood rubies:

London Mine Gambling

London has periodical investment or gambling crazes. At one time it is railway "securities," so called, at another the bonds of some bankrupt State, at still another some South Sea bubble in the shape of Indian or African gold mines. At present the fever is African and Burmese….

The latest London craze was finely exhibited at the recent allotment of shares in the Burmese ruby mines, concerning which our well-informed London correspondent wrote us February 15th: "The mines may be immensely valuable, or perhaps not; no one can tell as to this until a year's work has been done upon them." All London rushed to get the prospectus, and the crowd began to collect in front of the Rothschild's offices long before they were open in the morning. The £1 shares went immediately to £4, and the total amount of stock offered was applied for many times over.

These shares are "a pure gamble," even more than is usual in mining, though they have this advantage over most of the London mining stocks, that there is a possibility that they will pay, and pay largely, while the average London mining stock is absolutely certain never to pay anything.

Editorial, Engineering and Mining Journal

New York, March 16, 1889

The Company started its career with a paid up capital of £150,000 and a highly exaggerated view of potential production. All kinds of unforeseen difficulties were encountered during the first years, with an unusual amount of time spent in preliminary operations. The annual rental fee to be paid to the Government of India was originally fixed at the high sum of £30,000 per year plus 30% of any profits made, in return for the sole rights to mine with machinery. Native mining was also allowed by native methods in areas not utilized by the Company, for which a tax of 30% on all finds was collected. This tax soon proved unworkable and so a fee per workman was charged instead. Revenue from native workings later became an important source of funds, but in the beginning little was collected.

|

Mogok--A city built on rubies Mogok has always been known as the city of rubies. Just how true this is was brought home when geologists and engineers first began to study the gem deposits of the area. They found that some of the richest alluvials lay right beneath the town itself and so in 1902, and again in 1908 and 1909, parts of the town were purchased and the people resettled elsewhere (Brown, 1933).

|

Tremendous difficulties were encountered from the outset. First, a road had to be constructed from Thabeitkyin to Mogok, through nearly 100 kms of densely-jungled hills 5 (George, 1915). Machinery had to be imported; diseases took their toll of men and livestock; flooding was common in the rainy season; these were but a few of the problems. Power generation was yet another obstacle. Coal was not practical as it would have had to have been brought from Thabeitkyin (Talbot, 1920). Steam pumps were used at first, but required too much timber. Since Mogok had plenty of water, it was decided to construct a hydroelectric plant. This was completed in 1898, the first of its kind in that part of Asia (Brown, 1933).

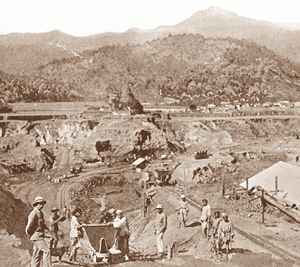

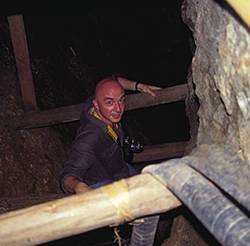

Figure 19. Bottom of the ramp at the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd. mine at Mogok, with both British and native workers. (From Claremont, 1906)

Figure 19. Bottom of the ramp at the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd. mine at Mogok, with both British and native workers. (From Claremont, 1906)

Although water helped in electricity generation, it remained the nemesis of miners at Mogok, continually flooding the workings. The company's engineer, A.H. Morgan, proposed a tunnel through the rock some 100 ft (30 m) below the surface and more than a mile (1.6 km) in length. Construction began in 1904 and finished in 1908. The tunnel was immediately successful in dewatering the diggings. 6 Unfortunately, its completion coincided with a downturn in the gem market, in part brought about by the development of Verneuil's synthetic ruby.

Introduction of cheap Verneuil synthetic rubies hurt sales, as did the economic downturn resulting from World War I. With losses mounting, the Company renegotiated its lease with the Government several times, but it was not enough. In 1925, faced with mounting losses, the Company went into voluntary liquidation. No buyers were forthcoming and so in 1931 the lease was surrendered. Thus ended the first attempt at mechanized mining of the world's richest ruby deposits.

Company postmortem

Many have speculated about the reasons for the Company's failure (Halford-Watkins, 1932a-d), most concluding that it was just not meant to be, the difficulties being too great to surmount. But evidence uncovered by the author suggests the Company owed its failure less to the difficulty of the task and more to that old devil we know--human greed. In a confidential report written to the Government of India on the future of mining at Mogok, the head of the Geological Survey of India, J. Coggin Brown, pointed his finger straight at the De Beers diamond cartel:

At this juncture I cannot refrain from writing an opinion which I have already expressed verbally, that the influence of the De Beers diamond concern has had more to do with the present [1927] position of mining for coloured gems in Burma than appears on the surface. The reasons for this are obvious, and it is significant that there has always been a powerful representative of the Great South African concern on the Board of the Burma Ruby Mines, Limited.

J. Coggin Brown, 1927

Gem Mining in the Mogok Stone Tract… (confidential report)

Brown was referring to the competition for a share of the gem market between De Beers and the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd. Apparently, he believed that the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd. was sabotaged by De Beers. This idea is not as far-fetched as it might seem. De Beers was not always the huge and powerful monopoly of today. It has taken over eighty years of monopolistic practices and masterful marketing to reach such a position of dominance.

|

Marching on Mogok It was anticipated that we should not reach this unknown country without meeting with some opposition, and on Nov. 15th [1886] a force of Shans was found stockaded in our front on the Kodan River. The ground they had chosen was a spot on which two years previously an army of Theebaw's had been completely routed. A successful flanking movement, however, cleared them out completely in a little over an hour, several dead and wounded men being left behind. No more opposition being met with, Sagadoun at the foot of the hills was reached and occupied, and a halt was made for a few days. From here, 6000 feet above us, glittering in the sun, could be seen the peaks of Shwee-ov-Toun, which were promptly christened Sheba's breasts, from their supposed likeness to the hills that guarded King Solomon's mines, and lesser peaks covered with jungle forest, from which peeped out a native village or a green patch of cultivation. On Dec. 18th the march up the hills began. The only transport that could be used along these mountain tracks was that of pack mules and ponies, and hard work these poor beasts found it, often ascending 2000 feet in a day, and many a man wondered as he tramped along if his kit and food would reach him before midnight. At each camp new and curious views would open themselves out before us; at one point the plains and hills between us and Bhamo could be seen stretching for miles and miles in the bright evening sunlight; next morning the same country would be covered with white clouds floating far below our position, appearing like some huge snow field. Again, at another camp would be discovered away to the east some mountain range of Yunnan veiled in blue mist. As the force proceeded, the Shans and Dacoits fell back, evacuating one strong stockade after another, till at last, on the morning before Christmas Day, we reached a point at the end of a narrow valley where the hills rose high above us, and through which two narrow passes lead directly into the Ruby Mine district. It was found that these passes were strongly stockaded, and held by the enemy in force. General Stewart determined to attack the position on our right front first, as it would otherwise command our flank. A few shells were first dropped into it, and then an attacking party moved forward; in about an hour a ringing cheer informed us that the stockade was taken, and soon its former occupants could be seen scuttling over the hills, conspicuous in their white jackets and large straw hats. It was too late, however, to give proper attention to the stockade on our left which commanded the road to Mogok; so camp was pitched, and on the order bugle sounding it was found that we were to spend a quiet Christmas Day, for the last few days' work had exhausted both men and beasts. At an elevation of about 6000 feet, the morning of Dec. 25th dawned in quite an English fashion; a heavy white frost covered the ground, and bitter were the complaints at the coldness of the night. The popular Padre of the force held divine service and the day passed quietly. Next morning the column started early, but only to discover that the series of stockades on our left had been abandoned: they had been most carefully constructed and cleverly masked, and would, properly held, have formed a very formidable obstacle to the advance…. …[Due to the head man absconding with the payroll], the opposition against us evaporated and we entered the Ruby Mine valleys of Burma without firing another shot. On the morning of January 27th the last ridge overlooking Mogok was reached and the town lay at our feet. G. Skelton Streeter, Mogok, March 8, 1887 |

Early in the 20th century the diamond market faced the real problem of oversupply, due to discovery of vast new deposits in South Africa. It takes no great leap of faith to see that, from De Beers' perspective, the potential success of the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd. represented a substantial threat. Of course, one cannot sell rubies if they are not being mined and effectively marketed. According to Brown, poor decisions taken by the Board of Directors of the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd. greatly contributed to the venture's eventual failure. 7

In his summary, Brown discussed the future potential of ruby mining in Burma:

The operations of the Company, apart from an abortive attempt to mine gems from the limestone, and one or two half-hearted efforts to prove the hill deposits, have consisted entirely in working the valley alluvials, confining their attentions to the Mogok, Kyatpyin and Kathe Valleys. There are, however, other valleys in the stone tract and the question arises whether these have been sufficiently explored. It is exceedingly doubtful if they have, in particular the Kin and Khabine [Kabaing] deposits. It is notoriously difficult to prospect this type of mineral deposit and no two geologists of experience would agree as to the reliability of the results so obtained. But it was surely the duty of the Company to put these questions beyond doubt. This has not been done, not through any fault of the local technical command but owing to the inhanition of the Board of Control…

It has been stated to me repeatedly, and I see no reason to doubt the fact from my own view as a geologist, that there are great possibilities in the hillside deposits. They will certainly be more difficult to evaluate and occasional failures might result, but, in a speculative business like gem mining perhaps this does not matter much…. The history of the Company proves that time after time the selection of a field for a new enterprise instead of being a matter of scientific certainty, has been a pure speculation, based for the most part on reports and rumours of the success of native miners.

J. Coggin Brown, 1927

Gem mining in the Mogok Stone Tract… (confidential report)

Burma after the company

In the years after the failure of the Company, the working of the mines reverted to the age-old methods of native miners. Company machinery lay fallow and eventually became useless. The fantastic drainage tunnel designed by A.H. Morgan was damaged by heavy flooding in 1925 and never repaired, resulting in the formation of two large lakes which today dominate the landscape of Mogok.

New rules for mining took effect in 1930, which allowed homesteading upon payment of a Rs10 per miner fee (Ehrmann, 1957b). The result was a proliferation of small mines. Some machinery and the electric plant were sold to A.H. Morgan and a Mr. Nichols (or Nicols; Meen, 1962). Morgan later died, but Nichols continued to supply electricity to the area at least through 1962. By 1957, some 1200 individual mines were in operation, employing anywhere from 2–50 people each. Miners were also shareholders, splitting the profits with mine owners, which helped to eliminate theft (Ehrmann, 1957b). 8

In 1962, a military coup brought General Ne Win to power and plunged the country into isolation. Ne Win called the new direction the "Burmese road to socialism," but many thought the "Burmese road to poverty" a more apt label. With the exception of roadside food stalls, most industries were nationalized.

Figure 20. The search for crimson infects both young and old. Inn Gaung (`Big Hole Mine'), Mogok. (Photo: Thomas Frieden)

Figure 20. The search for crimson infects both young and old. Inn Gaung (`Big Hole Mine'), Mogok. (Photo: Thomas Frieden)

Gem mining was fully nationalized in 1969 ( Mining Journal, June, 1970) and private trading of gems outlawed. In fact, mere possession of loose stones was a crime. 9 After nationalization, the government worked the mines in a rather desultory fashion. Mechanized mines were operated, but with little success, as the generals placed their military cronies in positions of power, rather than trained engineers and administrators. The little output that did fall into government hands was sold at the annual auction in Rangoon, operated by the state-run Myanma Gems Enterprise (MGE). 10 Illegal mining also took place and accounted for the lion's share of production. These stones eventually found their way onto the world market through the porous borders of Thailand, China and India.

Smuggling became the norm, so much so that the black market was dubbed the "brown market" by Burmese, due to its ubiquity. At Mandalay's night market one could find all manner of smuggled foreign goods openly on sale, while, at the jade mining and trading town of Hpakan, the goods offered were even more exclusive. French cognac and champagne, American cigarettes, perfume from Paris, all were readily available for those willing to pay the price (Lintner, 1989).

Burma today

In 1988, anti-government riots wracked the country and were ruthlessly crushed. Realizing the degree of popular discontent, the years following the riots have seen an ever-so gradual loosening of controls on the country's economy. In 1989, MGE began to accept privately-owned gem and jewelry consignments for offer at the annual auction and at its retail shops. Private-government joint ventures in gem mining were started, as were joint ventures with foreign companies for jewelry manufacture. The holding of foreign currency was also legalized, eliminating the need for sacks of the local kyat, which is available in small denominations only. In April, 1994, the gem export tax was reduced to a near-reasonable 15% (U Hla Win, pers. comm., May 2, 1994). But in today's highly competitive business climate, only when such restrictions are entirely eliminated can smuggling be erased.

Today, the seed of a local jewelry-manufacturing industry in Burma has been planted, but it will take years to bear fruit. As of the present writing, Burmese jewelry cannot compete with that manufactured elsewhere; most foreign buyers of Burmese jewelry are strictly interested in the gems, with the settings being used for scrap once out of the country.

From the developments of the past few years, it is clear that big changes are afoot in Burma's gem and jewelry industry. The world will certainly welcome such moves if they lead to true economic and political freedom.

The current situation in Mogok

Prior to 1991, information on Mogok's mining situation was difficult to obtain. The biggest problem was the totalitarian nature of the Burmese government, which regards even mundane details about the country as state secrets. Until 1991, foreigners were not permitted to travel to Mogok. E.J. Gübelin (1963, 1965, 1966) was one of the last foreign gemologists to visit the area, in the early 1960s.

During the mid-1980s, the author had a chance to discuss the, then current, mining situation with a longtime resident of Mogok. Photographs were also obtained, revealing that little had changed in Mogok since the early 1960s. Private mining had long been banned throughout Burma, but in a town of several thousand people whose sole means of income is mining gems, the government was forced to turn a blind eye. Just as in former times, a gem market was held once a week in Mogok at the parade grounds and traders came from far and near to attend. Cheaper goods were displayed openly, while more expensive stones were sold behind closed doors in small sheds which lined the edges of the grounds.

Beginning in 1991, foreigners were again allowed to visit Mogok (Ward, 1991; Kane & Kammerling, 1992). What they found was little changed from the time of the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd. Today, just as in the time of the company, mechanized mines coexist with traditional workings, and smuggling continues to be a big problem.

|

Borderlands Burma is home to one of the planet's richest sources of gem mineral wealth. Since 1962, it has also achieved notoriety of a different sort--home to one of the planet's most repressive regimes. The country today known as Myanmar (Burma) was, before the British colonial period, a patchwork of tributary states populated by diverse ethnic groups, including Shan, Kachin, Karen, Karenni, Pa-O, Mon, Wa and others, loosely ruled by the Burmese monarch. Under the Burmese monarchs, such groups paid tribute, but the capital had little direct influence. British rule succeeded in uniting the country, but when it became clear that colonialism was at an end, long-simmering dreams of ethnic independence quickly boiled over. In order to prevent fragmentation of the country, a constitution was drawn up allowing any of the member states to secede from the Union of Burma if they felt it necessary. It was only by adding this clause that the non-Burmese ethnic states agreed to join the Union. Independence came in 1948, but problems arose almost immediately, with the ethnic states feeling neglected in terms of development money and support. The Karens were the first to resort to armed struggle, shortly after independence. In 1958, the Shans followed, and, in 1961, the Kachins. This was the beginning of the still-ongoing civil war (Lintner, 1990). Many rebel groups use smuggling to raise revenue. Whether by foot, road, river, rail, elephant or mule, manufactured goods from Thailand and elsewhere travel into Burma, while gems, narcotics, gold, silver and other raw materials move outward in a never-ending stream. Smuggling routes from Burma's gem mines to the outside world are varied and constantly changing. From Mogok, gems may pass by road east through Kengtung, to reach Mae Sai in northern Thailand. This route has, of late, become particularly popular for the new ruby from Möng Hsu. Another popular route, which has been eclipsed to some degree, takes one by rail or road to Moulmein, south of Rangoon. From here, it is but a short 1–2 day walk to Mae Sot in Thailand's Tak province. Still another route leads westward into India or Bangladesh. With the opening up of China's economy, much jade now proceeds directly from the mines in Kachin State, to Kunming, capital of China's Yunnan province. And reports have it that rubies and sapphires are also finding their way along this route (Robert Frey, stolid comm., May 3, 1994). Current government policy is to make peace with the ethnic guerilla groups. As of May, 1994, a number of them had laid down their arms (Lintner, 1994a-b).

|

Mining areas

It is somewhat fruitless to describe precise mining areas because the situation is constantly in flux. As with most mining areas, mines continually close and new ones open, as deposits are exhausted and new ones discovered. Illegal mining (and cutting) generally takes place in more inaccessible regions and is sometimes supported by armed rebel groups. As of 1992, the Burmese government was operating eight mechanized mines in the Mogok area, seven for ruby/sapphire and one for peridot. Both open cast and tunneling are being used. MGE operates two tunneling operations, one at Lin Yaung Chi for ruby and another at Thurein Taung for sapphire. Byon from the various mines is either separated on site, or transported to the MGE Central Washing Plant (Kane & Kammerling, 1992).

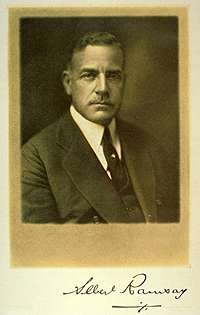

Figure 24. Photo of Albert Ramsay, who purchased and cut the Gem of the Jungle. (From Ramsay, 1925)

Figure 24. Photo of Albert Ramsay, who purchased and cut the Gem of the Jungle. (From Ramsay, 1925)

In addition to government mines, since 1990, the government has allowed private/government joint ventures, which as of 1992 numbered in the hundreds. A number of joint-venture primary-source mines operate near Kyauk Saung, as well one at Dattaw (Dat Taw).11 The later is famous as the source of the SLORC ruby (Kane & Kammerling, 1992).

The mine at Myintada, near the town of Mogok, is famous for fine quality star rubies and sapphires, with facetable ruby and fancy spinels also being found in quantity. Near the town of Kathé (famous for sapphires) is the government mine at Pingu Taung (`Spider Mountain'), where fine sapphires are found. To the west of Pingu Taung is another government mine at Kyaukpyatthat-ashe. In addition to sapphire and ruby, a number of other gems, and even uranium, are also mined.

These are but a few of the localities where mining is proceeding today. Rubies are found in virtually all of these localities, along with spinels and zircons.

Other gems from the Mogok area

Other than corundum, the Mogok area produces fine gems of many species. In this regard, Mogok is, next to Sri Lanka, probably the most prolific source of gems in the world. Chief among these is the spinel, which historically was often confused with ruby. Although occurring in many colors, Mogok produces the world's finest reds (including pink) and oranges, bar none. Not only are the cut stones magnificent, but the area also furnishes the world's finest crystal specimens. Locally termed am nyunt-nat-thwe (`spirit polished'), the perfection of these crystals is such that they are often set into jewelry as is. At Kabaing, pink spinels are mined, while just south from Kabaing, at Sakangyi, hot pink rubies are obtained. Near the town of Kyatpyin are obtained the world's finest red spinels, while many ilometers north, at Pandaw, the best pink spinels are found.

Some of the world's finest peridot is mined at Pyaung Gaung, near Bernardmyo, with cut gems sometimes larger than one hundred carats, while the world's rarest gem mineral, painite (named after its finder, longtime Mogok resident, A.C.D. Pain), has been found near Ongaing.

The following are among the species mined in the Mogok Stone Tract, based on the author's own research, on Kammerling & Scarratt et al. (1994), and U Hla Win (pers. comm., Feb. 1994). In parentheses are the Burmese names for the gems.

|

Gem species of the Mogok Stone Tract Gem type

|

Mining methods

Figure 26. Twin-lon mines and native miners at Mogok, Burma. (From Iyer, 1953)

Figure 26. Twin-lon mines and native miners at Mogok, Burma. (From Iyer, 1953)

The rubies of Mogok occur in a crystalline limestone (marble) matrix believed to result from a combination of both contact and regional metamorphism. In contrast, the sapphires are derived from a number of different igneous rocks, including biotite gneisses, urtite veins intruded into marble (Kane & Kammerling, 1992), or pegmatites (Iyer, 1953). Weathering has transported both rubies and sapphires down from the hills to the valley floors where they have settled in the bottom of the streams and rivers to form part of the alluvium. It is from these ancient river gravels that the majority of the stones have been recovered.

Four traditional types of mines exist in Mogok:

- The Twin-lon, or pit method, for mining the valley alluvials.

- The Hmyaw-dwin, or open trench method, for excavating hillside deposits.

- The Lu-dwin system for the extraction of gem-bearing materials that fill limestone caves and fissures.

- Quarrying (tunneling) directly into the host rock to extract rubies and sapphires.

Since the time of the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd., these have been supplemented by open-cast mechanized mines.

Twin-lon

Twin-lon or "twin" mining involves the sinking of a small round shaft or hole down to the gem-bearing gravel, which is locally termed byon. Miners believe that an area is rich in rubies where big chunks of quartz are found in the byon (Iyer, 1953). Each mine is generally worked by two to three men, similar to traditional gem mining in Thailand and Sri Lanka. Two of the men take turns digging the shaft while the third stands above-ground lowering a small basket to haul up the earth. This basket is attached to the end of a long bamboo pole with a counterweight, or a hand-cranked winch, to assist in lifting the earth. Depths of these twins vary with the depth of the gravel and range from 3–24 m (10–80 ft). Light is provided by ingenious manipulation of a looking glass or reflector at the shaft's mouth so that a beam is thrown down to the bottom. Candles may also be used.

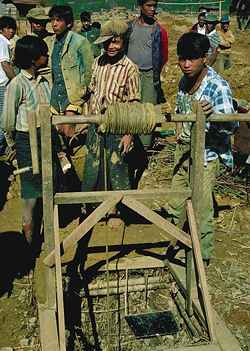

Figure 27. Raising gravel from a lebin (square pit) at Mogok's Inn Gaung (`Big Hole Mine'). Note the foil reflector at the pit entrance, which is designed to direct light to the pit's bottom. (Photo: Thomas Frieden)

Figure 27. Raising gravel from a lebin (square pit) at Mogok's Inn Gaung (`Big Hole Mine'). Note the foil reflector at the pit entrance, which is designed to direct light to the pit's bottom. (Photo: Thomas Frieden)

Once a layer of byon is reached, horizontal tunnels are driven for distances of up to 9 m (30 ft) to remove as much paydirt as possible. Shallow shafts need no shoring up, but the deeper ones are firmed with posts. Even with these precautions cave-ins do occur on occasion and may be fatal. Flooding from groundwater is a constant problem and the first job each day is to remove the previous night's accumulation of water. Ingenious pumps made from bamboo have been devised for this purpose. Today these are supplemented by diesel-powered pumps. Generally, twin-lon operations can only be carried on in the dry season (Nov.-May).

Larger excavations, shored up by timber, twigs and leaves, are termed lebin and kobin, and the biggest, inbye. These are used in areas where the earth is not compact enough for twinlons. The inbye is rarely seen due to the expense of the timber needed (George, 1915, p. 77).

Hmyaw-dwin

Hmyaw-dwin mining consists of open cuttings on the sides of hills. J. Coggin Brown was earlier quoted as feeling that great potential still remained for this type of mining. A stream of water, sometimes brought from great distances via bamboo or plastic channels, is directed to the upper end of the working under pressure. This carries the mud into the tail race of the excavation, with the lighter material being swept away. The heavier concentrate is then carried to a suitable site for washing. As this method requires plenty of water, it is used mainly in the rainy season (June-October).

Figure 28. A Burmese miner at Mogok dewatering an excavation using an ingenious bamboo pump. (From O'Connor, 1905)

Figure 28. A Burmese miner at Mogok dewatering an excavation using an ingenious bamboo pump. (From O'Connor, 1905)

Lu-dwin

The lu-dwin ('loo') is the least common of the three traditional methods of mining in Mogok. These are excavations into the sides of the hills, following the gem-bearing material through the crevices and caves in the limestone. It is within these caverns and crevices that some of the richest finds have been made. One cavern proved so vast in size and the depth of the byon so great, that hmyaw-dwin and twin were actually set up inside the cavern itself. Unfortunately the roof caved in, putting an early halt to the proceedings (Halford-Watkins, 1932a). According to George (1915, p. 76), the danger attending this method was overstated. However, just before Kane and Kammerling's 1992 visit, they were told that several miners had died in a cave-in at a lu-dwin at Than Ta Yar.

Such caves form as a result of impurities in the limestone. Groundwater dissolves the limestone, forming cavities. More resistant minerals, such as rubies and other gems, concentrate in the loamy soil on the cave bottoms. Miners will crawl through tiny crevices in the limestone to reach concentrations of byon. This will then be hauled to the surface for washing. One particularly rich lu-dwin near Bobedaung (Bawpadan) was termed the "Royal Loo"12 because it produced a number of stones of such high quality that they had to be turned over to the king. In 1996, the author was given a grand tour of the now-abandoned Royal Loo at Bawpadan. The entrance consists of a narrow tunnel into which one must crawl.

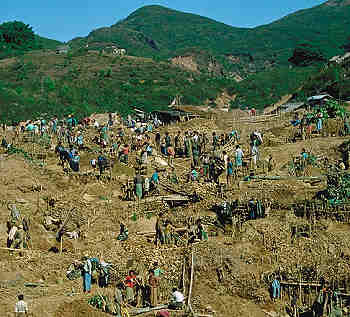

Figure 29. Although hillside deposits were largely ignored during the British period, today they represent virgin ground. Here, at Inn Gaung (`Big Hole Mine'), in the Mogok area of Burma, miners tunnel like ants, occupying an entire hillside in their quest for the red stone. This drama has been played out throughout human history, a continuum of our species' pursuit of dreams, ego, wealth and power. Some make it big; too many others are left with only the dream. (Photo: Thomas Frieden)

Figure 29. Although hillside deposits were largely ignored during the British period, today they represent virgin ground. Here, at Inn Gaung (`Big Hole Mine'), in the Mogok area of Burma, miners tunnel like ants, occupying an entire hillside in their quest for the red stone. This drama has been played out throughout human history, a continuum of our species' pursuit of dreams, ego, wealth and power. Some make it big; too many others are left with only the dream. (Photo: Thomas Frieden)

Quarrying

C. Barrington Brown (Brown and Judd, 1896) described a fourth method of mining – quarrying or tunneling into the host rock itself, which is a slight variation on the lu-dwin. At the time of Brown's visit in 1887, miners were using a gunpowder of local manufacture. However, this often damaged the gems. Today, more sophisticated types of blasting are used to extract both ruby and sapphire from their host rock (Kane & Kammerling, 1992).

Mechanized mining

Figure 30. French gem dealer, Olivier Galibert, descending into a lu-dwin at Kadoktut, near Bawpadan. We asked the miners how deep it was. They answered that their rope was 5000 ft. long and it did not reach the bottom. (Author's photo, May 1996)

Figure 30. French gem dealer, Olivier Galibert, descending into a lu-dwin at Kadoktut, near Bawpadan. We asked the miners how deep it was. They answered that their rope was 5000 ft. long and it did not reach the bottom. (Author's photo, May 1996)

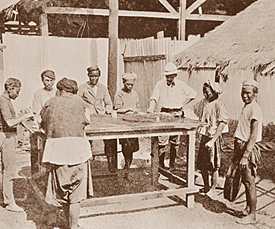

During the time of the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd., mechanized mines were operated at a number of different locations, and this continues today. The largest, at Mogok's Shwebontha mine, opened in April, 1894, and operated for years thereafter. These were generally open cuts, with the excavations being made by hand. First, a pit 10 sq ft (0.93 sq m) was sunk to a depth of 25 ft (7.62 m). This served as a water sump, and a centrifugal pump was lowered into position to remove the water. Near this hole coolies would attack the byon by digging a hole and working outward on all sides, breaking down the walls and loading the earth into trucks. As the hole widened, it became possible to sink lower and lower. Workers dug away at the toe of the wall, and as the bank caved in, transferred the earth to trucks, with water being diverted to the pump pit. The trucks were hitched to an endless rope, which would haul the earth up a ramp to the washing plant, where it is tipped into screens and falls into the washing pans (Talbot, 1920).

At Shwebontha, this simple process developed into a huge gaping hole in the surface of the valley nearly a mile (1.6 km) in length. While not deep, it was mining on a grand scale. From January, 1895 to February, 1904, 4,820,000 truck-loads of byon were taken out of the ground at Shwebontha, and its extension at Schwelimpan. These resulted in gems worth over '485,000 (Talbot, 1920).

Washing the byon

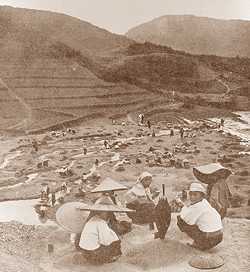

Figure 31. Native kanase women washing ruby gravel at Mogok, Burma, ca. 1905. (From Anonymous, 1905a, Booklovers Magazine)

Figure 31. Native kanase women washing ruby gravel at Mogok, Burma, ca. 1905. (From Anonymous, 1905a, Booklovers Magazine)

Once sufficient byon has been obtained, it is transported to the washing area. A shallow circular enclosure is formed with big rocks, the floor of which slopes slightly at one end. Into this the byon is placed and a stream of water directed onto it while the whole mass is stirred. Water and lighter debris flow out a small opening at the lower end, leaving behind the gems and heavier material. Eventually the opening becomes clogged with heavy gravel. This gravel is then removed for further washing on circular bamboo trays, similar to the method used in panning for gold (Halford-Watkins, 1932b). Today, byon is often stockpiled in the dry season, for washing in the wet season, when workings become flooded.

Output from mechanized mines goes to a washing plant, to be separated by machine. In the days of the Burma Ruby Mines Ltd., two separate washing plants were operated at Shwebontha, three at the Redhill mine, and one at Padansho, near Kyauklongyi (Brown, 1933). Today, the government operates a washing plant, where byon from government mines which do not have a plant on site is washed.

The kanase (kanes) custom

Almost inevitably, some of the gems escape and are carried away to the tailings. According to local custom, these tailings may be searched through by anyone, with any stones found becoming the property of the finder. Under the Company, however, this was later restricted to women only; any man who raised a stone from the ground, unless a worker or license holder, was subject to imprisonment. Thus, it is the women who search in this way. They are termed kanase women. According to Halford-Watkins (1932b), this custom resulted in the wholesale theft of large numbers of stones from Company mines, as well as providing a convenient method for the disposal of stolen goods. The way it worked was as follows: a dishonest workman may catch sight of a stone. He would then pass it secretly to a nearby kanase woman or tell her where to search for it. Moments later, there is a shout of joy from the woman as she has just "uncovered" a stone which, by custom, is hers to keep. The Company went to great lengths to prevent the theft of stones, enclosing the sorting areas, requiring workers to wear steel masks so that stones could not be swallowed, etc. However, all this was to no avail because of the kanase custom.

Figure 32. Kanesé girl washing gem gravels in a stream in Burma's Mogok Stone Tract. (Photo by the author, May 1996)

Figure 32. Kanesé girl washing gem gravels in a stream in Burma's Mogok Stone Tract. (Photo by the author, May 1996)

Sorting and trading

Final sorting of the gravel is normally done by the mine owner, his relatives or other trusted staff, with another person present to keep him honest. All others are kept away. As stones are found they are placed into a bamboo container, or today, a plastic bag. At the end of the day, the contents are put into a packet, which is sealed on the spot if the owner has partners who are not present. This seal will only be broken in the presence of all the partners, again to keep everyone honest.

In the morning, stones found during the previous day's work are placed onto a polished brass plate for grading in direct sunlight. First the inferior material, termed sonzi, is removed and separated into three types: ruby, sapphire and spinel. This is later crushed for use as abrasive (Halford-Watkins, 1932b).

Those left on the plate are now graded roughly, by hand or sieve, according to size. The owner himself removes the best stones, for personal grading at a later time, with the remainder graded by sorters. First, lower qualities are arranged in small piles, then better stones. In the end, all are passed to the owner for final classification, assisted by the ubiquitous brokers, who play an important role in the valuation and sale. Valuations and bids are all done with the secret hand language so quaintly described earlier by Cæsar Frederick.

|

To catch a thief In a gem mining operation, it is absolutely vital that theft be kept to a minimum (it can never be eliminated entirely). If a significant portion of the production is stolen, these stones will appear in the marketplace, always undercutting the prices asked for legitimate production. The author was once told of one unique method of dealing with this problem. Two brothers purchased a gem mine in Africa. While one brother handled the daily affairs at the mine, the other set himself up incognito at the nearby town as a gem buyer, purchasing all of the stones stolen by his workers. Although they were buying stones that were rightfully theirs, the brothers were happy with the arrangement for it allowed them to control the entire production of the mine, and thus, to better influence the price.

|

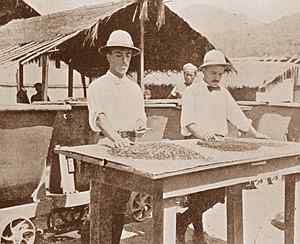

Figure 34. British sorters at the Company mines, at Mogok, Burma. (From O'Connor, 1905)

Figure 34. British sorters at the Company mines, at Mogok, Burma. (From O'Connor, 1905)

The role of brokers is important, both at Mogok and further north at the Hpakan jade mines. Each dealer employs them to act as his eyes and ears. Their job is not only to assist in valuations and sales, but also to obtain intelligence about what valuable stones have been recently mined, who the owners are, and, just as importantly, who the stones are being offered to and the prices bid. Owners of valuable stones do their best to keep details secret, for if a piece is bid upon, when the spies of other dealers learn of the bid, no one will offer more (Halford-Watkins, 1932b; W.K. Ho, pers. comm., ca. 1982). In other words, if one dealer believes it is worth only 50,000 Kyat, then why offer more? This situation results in purchases taking place in a cloak-and-dagger atmosphere as both buyer and seller seek to conceal their activities. Stolen stones in particular may be offered at remote jungle rendezvous', sometimes in the dead of the night with only a hand torch as illumination. Legitimate goods may also be offered in this way, being represented as stolen in the hope that this would increase the buyer's feeling that he is getting a steal of a deal (Halford-Watkins, 1932b).

Perhaps the best summary of the gem business in Burma was that of British officer, Major F.L. Roberts (Chhibber, 1934). Although speaking in reference to the jade business, he could just as easily have been discussing the ruby trade:

From the time jade is won in the Jade Mines area until it leaves Mogaung in the rough for cutting there is much that is underhand, tortuous and complicated, and much unprofitable antagonism. In my opinion the whole business requires cleansing, straightening and the light of day thrown on it.

Major F.L. Roberts,

former Deputy Commissioner of Myitkyina

Judging from the tone of his statement, it sounds like Major Roberts would have been just the man for the job, too.

Figure 35. When miners do find something, their market is close at hand. Here a small trader awaits the results of a byon washing session at Inn Gaung (`Big Hole Mine'). (Photo: Thomas Frieden)

Figure 35. When miners do find something, their market is close at hand. Here a small trader awaits the results of a byon washing session at Inn Gaung (`Big Hole Mine'). (Photo: Thomas Frieden)

|

Local classification of gems Through the many generations of trading in Mogok, a local classification system has evolved as follows (based on the author's interviews with Burmese and Thai traders; George, 1915; Halford-Watkins, 1932): Thai names

Burmese namesIndividual stones are termed lon-bauk. Ruby parcels are graded by size and color. First-water stones (deep rich crimson)

Second-water stones (bright crimson)

Third-water stones (bright light crimson)

Fourth-water stones ( Ahte-kya )

Parcels of lesser-quality stones

|

Notes

5. Starting as a mule track, it was later widened for carts until its fully-metalled completion in 1901–2. Before its completion, one convoy of carts took over six weeks to make the journey (George, 1915). [ return to chapter text ]

6. Heavy rains in 1925 caused a fall, blocking the tunnel, causing the valley to revert to its former state of a series of large lakes, which is how it remains today. [ return to chapter text ]

7. This opinion was probably only expressed by Brown because his report was confidential. In his public writings on the Burma ruby mines, Brown said nothing about it. [ return to chapter text ]

8. The above has been taken from the accounts of Martin Ehrmann. Readers should be aware that Mr. Ehrmann was not the most reliable of authorities; while his articles are rich in detail, they are also riddled with errors and misspellings. Unfortunately, his are virtually the only non-geological accounts for the period 1930–1960. [ return to chapter text ]

9. To circumvent this ban, Burmese gems were typically traded in cheap, base-metal settings, both in Burma and at the Thai border (based on the author’s OFE; post-1970s; number of stones observed: plenty). [ return to chapter text ]

10. Myanmar Gems Corp. was founded by the Ministry of Mines on April 1, 1976. It was renamed Myanma Gems Enterprise in 1989 (Kane & Kammerling, 1992). Beginning in 1996, the military-run Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings, Ltd. (UMEHL) has taken over much of the role formerly played by MGE. [ return to chapter text ]

11. This is probably the Dató of de Terra (1943). The name is said to mean "mercury." De Terra explored several rich cave deposits at Dató. [ return to chapter text ]

12. I probably shouldn't mention the British meaning of that term. [ return ]