The subject of andesine in Tibet has been one of controversy since 2008. This article examines the history of the issue, along with detailing an October 2010 visit to the Tibetan andesine deposit.

Hunting Andesine in Tibet • How about a trip to Shangri-la?

It was autumn of 2008. I was in a car on my way to Chanthaburi when a friend called. "Fancy a trip to Tibet?" Gautama H. Buddha, man, don't do this to me. Of course I'd like to go to Tibet! Why? "To visit the Tibetan andesine mines." Yes master, when do we go? "End of next week." Wow, we'd better get some visas PDQ.

Alas, it was not to be. Despite frantic calls to Christina Iu in Japan, who was helping organize the trip, we were a day late. Next time, Christina promised, next time. "Okay," said I, "next time," and began to quickly plot when the high passes would next be clear enough for vehicular transport.

Forward to Spring 2009. At a conference in China, I met the inimitable Christina in the flesh and reminded her of her promise. Next time, right? Yes, yes, yes, next time. Wagging a finger, I warned I would hold her to that promise. Or else…

So what was my interest in Tibet? I'd been nibbling around the edges of that remote land for over three decades. It was on the road to Dharamsala (India; home to the Dalai Lama) in 1976 that I encountered my first Tibetans. A later foray to Manali (northern India) fanned the flame. But the bonfire was truly lit that same year when I visited Nepal. After two months in the Kingdom, including a lengthy trek to Everest Base Camp (within spitting distance of Tibet; no bathing for a month; don't ask me what I smelled like at the end), I was smitten with Tibet and all things Tibetan. Numerous later treks in Nepal only served to ratchet up my desire to someday visit the land of Shangri-la.

Figure 1. Map of Tibet, showing the location of the andesine mines. Map: Richard W. Hughes

Figure 1. Map of Tibet, showing the location of the andesine mines. Map: Richard W. Hughes

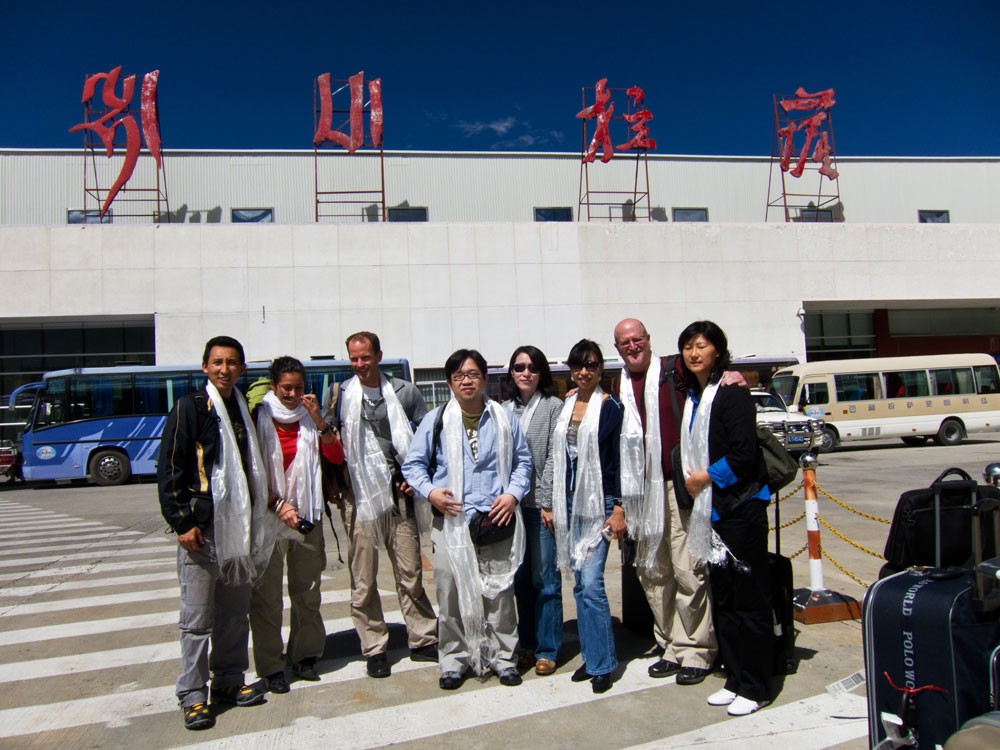

Figure 2. Team Tibet 2010 on arrival at Lhasa airport. From left to right: Ahmadjan Abduriyim, Flavie Isatelle, Brendan Laurs, Thanong Leelawatanasuk, Young Sze Man, Christina Iu, Richard Hughes and Lou Li Ping.

Figure 2. Team Tibet 2010 on arrival at Lhasa airport. From left to right: Ahmadjan Abduriyim, Flavie Isatelle, Brendan Laurs, Thanong Leelawatanasuk, Young Sze Man, Christina Iu, Richard Hughes and Lou Li Ping.

A tale of two mines

I saw my first piece of red andesine in about 2002 while working for Pala International. The source was said to be the Congo. Later, when the Congo source was questioned, I was told the source was "Tibet." It wasn't something that really concerned me much. Even to this day I've never personally sold a single piece of andesine.

Sometime about 2004, I was first asked about the possibility that red andesine entering the market might be treated. I told the source (who unbeknownst to me was quite close to some Oregon sunstone miners) that anything was possible, but I had heard nothing about such a treatment. [see this link for a full description of events from Pala International's Bill Larson].

At the 2006 Tucson show, the same person said he had met a Chinese lady who had Tibetan andesine rough, and would I like to take a look at it. Sure. By now I was working in the lab for the AGTA Gemological Testing Center. So I went to meet the lady, one Jacqueline Li. She had a large pile of rough red andesine, and gave my friend and me one piece each. I did question her in detail about the mine location (I'm a guy who likes to go to mines and was looking for an excuse to visit Tibet). She showed me pictures of the mining area, which were consistent with what I knew of Tibet, but when I quickly sketched an outline of Tibet and asked her to pinpoint the location, she indicated a place in the Kham region. No problem there (I knew my Tibetan geography), but when I probed more deeply, it became obvious she had never actually been to the mine site.

This did not raise red flags. The gem business is full of people who pretend to be mine owners, or who really are mine owners, but who do their best to keep the actual locality secret. This is done for a variety of reasons. First, if claim jumpers don't know the location of the claim, they can't jump it. Second, many miners may not have legal rights to a claim, and so keep the location secret to avoid official interference in their mining activities. Third, government officials may get greedy and, even if a claim is properly registered, try to squeeze the miner for tea money or, in the worst-case scenario, push the miner off the claim and take it for themselves. Fourth… well, you get the picture.

Back in the lab, I carefully examined the single piece of rough she had given me, along with the piece given to my friend. There was nothing to indicate treatment of any kind. The core was red and the skin was greenish on each piece. Neither piece showed any signs of melting or heat damage. I sent them off to our head office in NY to do chemistry and never saw them again (much to my dismay, the specimens were misplaced and never again located).

Over the three and a half years I worked at the AGTA-GTC, I tested several thousand stones. Of those, I can only remember testing about 2–4 pieces of red andesine. These were checked like every other stone, under blind conditions, where I was unaware of the stone's owner or the suspected identity. In each case, I found no evidence of treatment, nor did my colleagues, who included some of the world's most experienced gemologists. Indeed, while andesines were sent to every major gem lab in the world during this period, I am unaware of any lab issuing a report stating andesine to be treated prior to late-2008 (when the possibility of treated andesine became common knowledge).

Suspicions surface

In the late Spring of 2008 the Guide's Stuart Robertson called to ask about treated andesine. I told him that I had heard the rumors for quite some time, but that the handful of specimens I had examined showed no signs of treatment. Stuart then pointed me to an article that featured photos from a Japanese lab. The Japanese photos showed what was described as andesines in various stages of treatment. After taking a look, I told Stuart the evidence was quite compelling and that my previous skepticism regarding andesine treatment was probably wrong. Three months later, I left the AGTA-GTC and joined GemsTV, a company that had long been selling quantities of red andesine. My first order of business was to completely revise GemsTV's enhancement disclosure policies, with particular attention to andesine. Shortly after I joined the company, it began began describing the stone as "origin unknown" and the enhancement as "HD = Heat + Diffusion (aka 'bulk' or 'lattice' diffusion)."

Figure 3. Pale yellow untreated andesine said to come from Inner Mongolia, flanked by two lots of deep red treated andesine. The three bags of rough on the right are natural Tibetan andesine. Untreated and treated Inner Mongolian andesines courtesy of Marco Cheung of Litto Gems. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 3. Pale yellow untreated andesine said to come from Inner Mongolia, flanked by two lots of deep red treated andesine. The three bags of rough on the right are natural Tibetan andesine. Untreated and treated Inner Mongolian andesines courtesy of Marco Cheung of Litto Gems. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Lower education

In the autumn of 2008, I asked one well-connected gentleman in Bangkok if he had heard anything about "treated andesine." He smiled and opened up his wallet and with it, extracted a business card and a story that still drops my jaw to the floor.

It seems that he knew someone who was approached by the son of a Chinese university professor. The good doctor had developed a process by which common pale feldspar could be converted into bright red stones and the son wanted to partner with a major gem company to move this material into the market. But the asking price was extremely steep (hundreds of thousands of US dollars up front as a non-refundable 'deposit' and an agreement to buy hundreds of thousands of dollars of andesine every month), so my source's friend declined to participate. Another partner was found.

Unfortunately, the professor liked his booze. During one of his benders, he inadvertently revealed the secret of his treatment to one of his customers. This resulted in the process being duplicated, with treated andesine being produced in more than one location in China.

According to my source, the professor's son was incensed at the loss of the secret process, and so had the offending party kidnapped. Wife No. 1 reportedly told the kidnappers "keep him." But Wife No. 2 had a certain attachment and, after many months in captivity, he was successfully ransomed.

Thus began the great treated andesine scam. Who was repsonsible? Obviously, the people who knew of the deception and did not inform those to whom they sold the stones. I have never seen a single shred of evidence that any member of any lab who subsequently tested these stones was aware of the fraud. If anyone has such evidence, send it to me or publish it yourself. Put up, or shut up.

To the mines!

But what of the Tibetan mines? Were they real, or were the stories just a smokescreen for the treated stone? In 2008, Ahmadjan Abduriyim of Japan's GAAJ and Masaki Furuya of the Japan German Gemmological Laboratory decided to get to the bottom of it. Working with a variety of Chinese sources, they learned there was an actual Tibetan locality for red andesine, and another in Inner Mongolia where pale yellow feldspar was being mined for treatment by the aforementioned diffusion process. And so Ahmadjan and Masaki did what any decent gemologist would do. They went to the source, visiting both deposits in the Autumn of 2008. Accompanying them to Tibet were a number of others. Among the gemologists on the trip, Ahmadjan alone visited the Inner Mongolian deposit. Samples were hand collected in both localities, as well as purchased from local villagers. Hand collected samples were carefully separated from those purchased, to maintain the proper chain of evidence.

Shortly after these visits, details were published and the yak dung hit the fan. Tibetan mines are real? How dare you! Mongolian mines? What utter nonsense! The internets went crazy with half-baked questions and out-and-out raw ignorance, the following being typical of the level of rhetoric:

The question that many ask: How could the GAAJ video show a dusty desert mine at an elevation in the Tibetan desert so high and dry that absolutely nothing can grow, and yet the video shows Mr. Furuya pulling mud pies full of perfectly matching rough out of the dark recess of the mine, out of the view of the camera?

The answer, of course, is that Tibet is not so high and dry that nothing can grow. Southern Tibet's treeline is among the highest in the world and while there isn't a lot of rainfall, there is some, and combined with snow and glacial melt, groundwater is present. Even in a desert one is likely to encounter moisture if you dig beneath the surface. If there were no groundwater, then how would all those bushes grow? What would the yaks and sheep eat? How would the barley to make tsampa (the staple of the Tibetan diet) be grown?

Figure 4. According to one internet pundit, this image from Ahmadjan Abduriyim's 2008 trip to Tibet shows tools that are too clean, the buckets without enough wear and the gemstones too perfectly matched to be representative of an actual mining operation. In order that readers can get a better look, Ahmadjan Abduriyim has provided an extremely high-resolution image. Make your own decision on these stones and tools. We report, you decide. Photo: Ahmadjan Abduriyim

Figure 4. According to one internet pundit, this image from Ahmadjan Abduriyim's 2008 trip to Tibet shows tools that are too clean, the buckets without enough wear and the gemstones too perfectly matched to be representative of an actual mining operation. In order that readers can get a better look, Ahmadjan Abduriyim has provided an extremely high-resolution image. Make your own decision on these stones and tools. We report, you decide. Photo: Ahmadjan Abduriyim

But the most precious part is where the same writer questions the very existence of the "Mongolian" feldspar mines:

We found nothing. No records of any Mongolian feldspar mine in any mining periodical. No articles or records of any kind. No listing in any Chinese or Mongolian mining associations. And absolutely no evidence or record anywhere of either the Tibet or Mongolian feldspar mine....other than this expedition reported by the GAAJ and JGGL. So we contacted the offices of the Mongolian Mining Journal and the Mongolian Mining Association.…

No evidence of any feldspar mine was ever uncovered and reported to our office by the Mongolian Mining Journal.....

But the most definitive answer came from the Deputy General Director of the Mongolian Mining Association....who is also the Commercial Director of Mongolrostsvetmet LLC.

Mongolrostsvetmet LLC is the largest mining operation in Mongolia for industrial grade feldspar.

Mongolrostsvetmet LLC is the world's foremost source of information on Mongolian feldspar mining.

So sorry. The mine visited and cited by Ahmadjan Abduriyim, was not located in Mongolia (the country), but in Inner Mongolia (an autonomous region of China). The critic's first clue that he was in the wrong place should have been the Cyrillic alphabet and Russian-sounding names. Writing to the Mongolian Mining Association to ask about a mine in Inner Mongolia is like writing to the Mexican Geological Survey for information on a deposit in New Mexico.

Even so, what does an internet search on feldspar from Mongolia reveal? When I read the above statement, I did just that. Googling "feldspar" and "Mongolia" doesn't reveal much, but if you have been properly trained in search technology, you can strike gold. It took me about ten minutes to locate a paper published on the Inner Mongolian deposit (Yue Cao, 2006, 'Study on the feldspar from Guyang County, Inner Mongolia and their color enhancement'). The publication date of 2006 is a full two years prior to the world learning that most andesine in the market was probably treated.

No problem there. Sometimes it takes months or even years for a discovery to make its way into the mainstream. But hey, where was that critic in 2006, when so many consumers were being suckered? Was that critic guilty of fraud because he was unaware of this paper and this treatment a full two years before it hit the streets? Was that critic part of a vast conspiracy? Inquiring minds need to know.

To the mines! Again! The 2010 Tibet expedition

About 2005, Chinese businessman Li Tong was in Lhasa, where he noticed attractive red stones for sale in the market. Upon enquiring further, he was told that they came from Tibet, in the vicinity of Shigatse. Eventually he traced the source to a small village in Bainang valley. In 2007, he formed a small company and began mining with the local villagers. In 2008, he arranged for the visit of Ahmadjan Abduriyim and Masaki Furuya.

By 2010, with the andesine issue still unresolved, Li Tong was persuaded to organize a second trip to the deposit by foreign gemologists. On this trip were the present author, along with Ahmadjan Abduriyim (GAAJ, Japan), Flavie Isatelle (geologist, France), Christina Iu (MP Gems, Japan), Brendan Laurs (GIA, USA), Thanong Leelawatanasuk (GIT, Bangkok), and Young Sze Man (Jewellery News Asia, Hong Kong). Li Tong and his wife, Lou Li Ping, were our gracious hosts. Their staff, He Qiong, rounded out the group.

The journey to Tibet's andesine mines begins in Lhasa, capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region. Flying in to Lhasa (3,490 m; 11,450 ft) from Guangzhou at sea level is quite a jolt to the system and several members of our party immediately began to feel the effects of Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS). But it would only get worse. The following day, we traveled by road from Lhasa to Shigatse, crossing two high passes in the process, one which topped 5000 m. Even the fittest of our party were now out of breath and within 24 hours, several had to visit the doctor for treatment as they were showing more severe signs of AMS.

Figure 5. He Qiong breathes from an oxygen pillow near Shigatse, while Thanong Leelawatanasuk does his best to suck in a bit more air. At 3,840 m (12,600 ft), Shigatse is high enough that visitors who fly in from sea level (as our party did) are extremely susceptible to acute mountain sickness (AMS). Approximately half of our party suffered from AMS during the journey to Tibet's andesine mines. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Figure 5. He Qiong breathes from an oxygen pillow near Shigatse, while Thanong Leelawatanasuk does his best to suck in a bit more air. At 3,840 m (12,600 ft), Shigatse is high enough that visitors who fly in from sea level (as our party did) are extremely susceptible to acute mountain sickness (AMS). Approximately half of our party suffered from AMS during the journey to Tibet's andesine mines. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Location

The Tibetan andesine mines we visited lie in two adjacent valleys approximately one hour's drive southeast of Shigatse. The easternmost valley is Bainang (Chinese: Bailang), while that to the west is Yu Lin Gu. They lie on opposite sides of the border between Bainang and Gyanze counties in Tibet's Tsang province. Due to a rather angry monk, who believed previous mining had disturbed the mountain spirits and thus brought flooding to his valley, we were prevented from visiting the Bainang diggings. Instead, our two-and-a-half days were spent in the Yu Lin Gu valley and the nearby villages. The Yu Lin Gu occurrences were unknown to outsiders at the time of the previous 2008 expedition.

Arriving at the Yu Lin Gu valley in the late afternoon of the first day, our party walked to the upper part of the valley (GPS: 29°03.08'N, 89°20.76'E; +4,102 m; 13,460 ft) along with Li Tong and several Tibetan villagers. One Tibetan pointed out a piece of rounded andesine on the scree slope and once we knew what to look for, it was not long before all were picking up "floaters" from the surface. (I will leave it to my fellow expedition members to describe the geology of the area in their reports, which are being issued simultaneously with this article). Stones were rounded with small pits filled with a whitish material and tended to occur in concentrations. We'd find a stone in one spot and quickly find a bunch more nearby, then would have to walk a few meters away to find another.

In this spot, the trained geologists in our party (Ahmadjan Abduriyim, Brendan Laurs, Thanong Leelawatanasuk, Flavie Isatelle) did try to locate potential source rock for the andesine, but could not find it in the limited time available. In addition, no andesine was found far below the surface at this locality.

Figure 6. A "floater" of andesine just to the right of the coin in Upper Yu Lin Gu valley. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Figure 6. A "floater" of andesine just to the right of the coin in Upper Yu Lin Gu valley. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

The following day, we again visited the Yu Lin Gu valley, but this time the lower end (GPS: 29°03.95'N, 89°20.88'E / +3,929 m; 12,891 ft), close to the village of Zha Lin. While other members of the party gathered in one spot, I noticed a Tibetan man quietly spinning wool while herding his sheep a fair distance away. Slowly approaching him so he would be comfortable with my camera and me, after a brief period, I motioned to his red shirt and then picked up an ordinary stone off the ground. He quickly understood what I meant and began carefully examining the ground where we were standing. Bending down right at my feet, he picked up a piece of andesine. I had been standing right on the stuff. Now I'm grinning like it's my birthday and he and I are both scurrying around pulling stones off the ground. Wow! This is the real deal!

Figure 7. A sheepherder displays a few pieces of andesine he picked up at Lower Yu Lin Gu valley, near Zha Lin village, Tibet. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Figure 7. A sheepherder displays a few pieces of andesine he picked up at Lower Yu Lin Gu valley, near Zha Lin village, Tibet. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Bush leaguers

Meanwhile, back at the ranch my compatriots are doing some grinning of their own, digging holes and finding andesine, both on the surface and under the ground. Good stuff, but still not good enough. Brendan, Ahmadjan and I knew we needed to do more. So wandering off from the rest of the party, the three of us resolved to choose a bush at random completely away from where others had been digging. We didn't want to leave anything to chance. We wanted to be able to entirely rule out the possibility that the deposit might be salted.

So, amidst an alluvial fan dotted with probably over a thousand small bushes, we chose one at random that had no signs that anyone had dug under or around it. And with no one else close enough to toss a stone our way and with no andesine visible on the surface, we commenced to dig beneath that bush.

Figure 8. Good bush

Figure 8. Good bush

In order to prove the existence of Tibet's andesine mines, Ahmadjan Abduriyim, Brendan Laurs and Richard Hughes selected a spot at random in Yu Lin Gu valley to excavate. To ensure the deposit had not been salted, excavation was done beneath a bush (above). The andesines found beneath this bush proved beyond doubt that the Tibetan mines are genuine. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

At this point, I should probably mention that digging holes is hard work. Digging holes at 4000 m (13,000 ft) is even harder work, particularly for people who two days earlier were sipping frosties at sea level in Guangzhou. But dig we did, in the name of science.

Figure 9. Ahmadjan Abduriyim carefully excavating beneath a bush in lower Yu Lin Gu valley, near Zha Lin village in Tibet's andesine mining district. While many were skeptical of the existence of Tibet's andesine mines, the andesines found under this bush proved beyond doubt that the mines are genuine. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Figure 9. Ahmadjan Abduriyim carefully excavating beneath a bush in lower Yu Lin Gu valley, near Zha Lin village in Tibet's andesine mining district. While many were skeptical of the existence of Tibet's andesine mines, the andesines found under this bush proved beyond doubt that the mines are genuine. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Did I mention that digging holes at altitude is tough? It's even tougher when you have to uproot a bush. Looks like a dainty thing on the surface, but because of the harsh conditions, much of the growth is underground, with thick twisted roots, all the better to anchor the sucker in the ground against the harsh Tibetan wind (there is a reason why everybody in Tibet has rosy cheeks). Like many extreme climates, growth is quite slow (the Tibetan snowy rhododendron grows at a glacial 36 mm per year).

Figure 10. A mud-covered piece of andesine lies in a shovel in Lower Yu Lin Gu valley, near Zha Lin village. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Figure 10. A mud-covered piece of andesine lies in a shovel in Lower Yu Lin Gu valley, near Zha Lin village. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

But back to the digging. We dug and dug some more, all the while trying to suck down as much oxygen as possible from the thin air. Ahmadjan was a virtual human hoover, no doubt driven by the thought of all the nasty lies that had been spread about him. After we had gone down half a meter or so, we spread the dirt out and, bingo, there it was, an andesine pebble, covered with the wet, subsurface earth. Yes! Yes! Yes! Yes! Yes! Yes! We had our proof. After we had tagged and bagged it, we shouted out to the others to come over and have a look. It was Liberation Day for Li Tong, Ahmadjan and a bunch of others who knew the Tibetan stone was real, but had been subject to two years of lies and character assassination.

Figure 11. Liberation Day

Figure 11. Liberation Day

Li Tong and Brendan Laurs shortly after we found andesine beneath a randomly chosen bush. Li Tong has worked for years to show the world that Tibetan andesine is real. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Following the first discovery, we continued to dig in the hole beneath the magic bush and extracted a few more specimens. Two further holes were excavated beneath randomly chosen bushes some distance away from the first. One yielded no stones, but in another we also found andesine well beneath the surface. Being the eldest member of the expedition, I wisely allowed the younger people to gain experience in digging holes at altitude. Did I mention digging holes in thin air is tough? Yes, I guess I probably did. While they dug, I worked the crowd of Tibetan villagers who had by now gathered to watch the whacky foreigners hack away at the earth. Many of them had andesine, including one man with a large piece of cloth filled to the gills with the red stone (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Handful of andesine near Zha Lin village, in Tibet's andesine mining district. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Figure 12. Handful of andesine near Zha Lin village, in Tibet's andesine mining district. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

The salt trade

Definition of a mine: A hole in the ground owned by a liar. Mark Twain

In my gemological career, I have probably chewed through as much of the gemological literature as most anyone. In all those years, I cannot remember a single case where a gem mine was deliberately salted and the fraud was not immediately discovered.

The same cannot be said of mines for other minerals. A former colleague once told me that a method of salting tin mines in Malaysia was for the drill operator to casually tip the ashes of a cigarette into the test drill hole, along with a bit of tin carefully concealed in the cigarette. In these types of mines, even a few grains could vastly skew the assay results and sway investors' opinions.

Gem mines are an entirely different beast. Unlike precious metals, precious stones tend to be spread sporadically in a deposit, which is why test drilling is notoriously fickle. With gem placers, it is possible to salt a jig load, even a jig clean-up, but if one carefully digs holes at random across a large area, where there are no "local helpers" present, it is practically impossible to deceive a wary observer.

In the case of the Tibet mines, when it came to our visit, there were no investors to sway. Only local people, along with a Chinese trader, who were shocked at the suggestion that the stones they've been picking up off the ground for generations were anything but natural.

Anti-intellectual

As an American, I am sad to report that, among my fellow countrymen, there is a widespread notion that intellectualism is bad. Many profess a desire for their leaders to be just like them, the "common man." And thus American politicians are often forced to effect an "aw shucks" hick mentality in order to be elected.

I don't want poorly educated leaders, nor a "dumbed down" acting job. I want my leaders to be smarter than me. I speak only two languages; my daughter speaks three. I hope her children will speak four or five. Why send your children to school if you don't want them to learn? I believe learning is a good thing, that it will help us make better decisions. Not a guarantee, but a hedge on the bet.

As Jacque Fresco of the Venus Project has pointed out, if we look at human history, it is technological change that makes real, positive, measurable differences in peoples' lives, rather than religion or politics. Buddhism never cured polio, and neither the Democratic or Republican parties in America developed high-yield grains. Science and technological development did both. Science and technology are all about intellectualism. Key to technological development is "peer review" (see box) and the circle of understanding, where suppositions are put to the test of experimentation.

And yet, when it comes to a number of people, including some in the gemological community, we have a strong undercurrent of anti-intellectualism, where primitive instruments are "better" than complex ones, where cautious judgment is a sign of "weakness," where exploration and experimentation are unnecessary because "we already know." Taken to the extreme, on certain internet forums this has morphed into a Khmer Rouge-style world where anyone with advanced training, anyone working for a major gemological lab, or anyone who simply disagrees, is suspect.

|

Possibilities In the beginner's mind, there are many possibilities; in the expert's mind, there are few. Shrunryu Suzuki I have taught gemology in the classroom for many years and also spent a number in the lab. By far the most common mistake made by myself and my fellow gemologists and students is calling a natural stone synthetic or a natural stone treated. The reason is often complex, but generally because we fail to consider enough possibilities. We make assumptions and, in doing so, narrow our minds to the point where the only possible answer is the assumption we originally made, before we even started our testing. This is simply human nature, but thankfully, science has an answer. It is called peer review. In order to be accepted as fact, findings are published and subject to verification by others. This includes critics. If others cannot validate the findings, then less weight is given to them, compared with those that are validated. |

Figure 13. A sampling of andesines hand-collected by us in the Yu Lin Gu valley. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 13. A sampling of andesines hand-collected by us in the Yu Lin Gu valley. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

The 18 percenters

NY Times columnist Frank Rich wrote a piece entitled “Facebook Politicians are not Your Friends." Here’s a selection:

Nowhere, perhaps, is the gap between the romance and the reality of the Internet more evident than in our politics. In the idealized narrative of digital democracy, greater connectivity has bequeathed more governmental transparency, more grass-roots participation and even a more efficient rendering of political justice. Thanks to YouTube, which arrived just a year after Facebook, a senatorial candidate (George Allen of Virginia) caught on camera delivering a racial slur was brought down swiftly in 2006. Not long after, it was the miracle of social networking that helped enable Barack Obama’s small donors to overwhelm Hillary Clinton’s fat cats, and his online activists to out-organize her fearsome establishment pros.

But you can also construct a less salutary counternarrative. For all the Obama team’s digital bells and whistles, among them a lightning-fast site to debunk rumors during the campaign, Internet-fed myths still rage. In a Pew poll in August, 18 percent of Americans labeled the president a Muslim — up 7 points since March 2009. The explosion of accessible media and information on the Web, with its potential to give civic discourse a factual baseline and hold politicians accountable, has also given partisans license to find only the “facts” that fit their prejudices.

Frank Rich, Facebook Politicians Are Not Your Friends, NY Times, 10 Oct., 2010

There is no doubt that Tibetan andesine has been the subject of great controversy. Much ink has been spilled debating the pros and cons of the deposit, the vast majority by armchair pundits who have never come within spitting distance of a real Asian gem mine, let alone one in a locality as remote as Tibet.

I am fully resigned to the fact that nothing I say, write, or document will open the minds of certain people. They have so much invested in their version of events that it would be hara kiri to actually admit there is a natural andesine mine in Tibet. Let alone one that produces stones with features they have been claiming are proof of diffusion treatment.

Having done battle on various internet forums with these people, I have no expectations of epiphany from that direction. The eighteen percenters will continue to believe that Barack Obama is Muslim, that he was not even born in the United States, that there is no natural andesine mine in Tibet.

Thus it is not to the eighteen percenters that I pen these words. Instead, it is to those whose minds are curious and open to the possibility that, despite what was likely a massive fraud committed by a professor and his son, who secretly treated feldspar and foisted it on an unwary public, there is a natural andesine mine in Tibet.

In the end, it is the job of gemologists to try and figure out a way to separate these stones from those that are treated. That is consumer protection. Not simply crying "fire" in a crowded marketplace every single time you find something you cannot understand or explain. The fact that more than two years after the original expedition to the Tibet mines, the matter is still unresolved is not evidence of conspiracy, but complexity. This is a tough nut to crack. From synthetic amethyst to treated diamonds, gemology today has a number of challenges. Separating treated andesine from the natural stone is one of them.

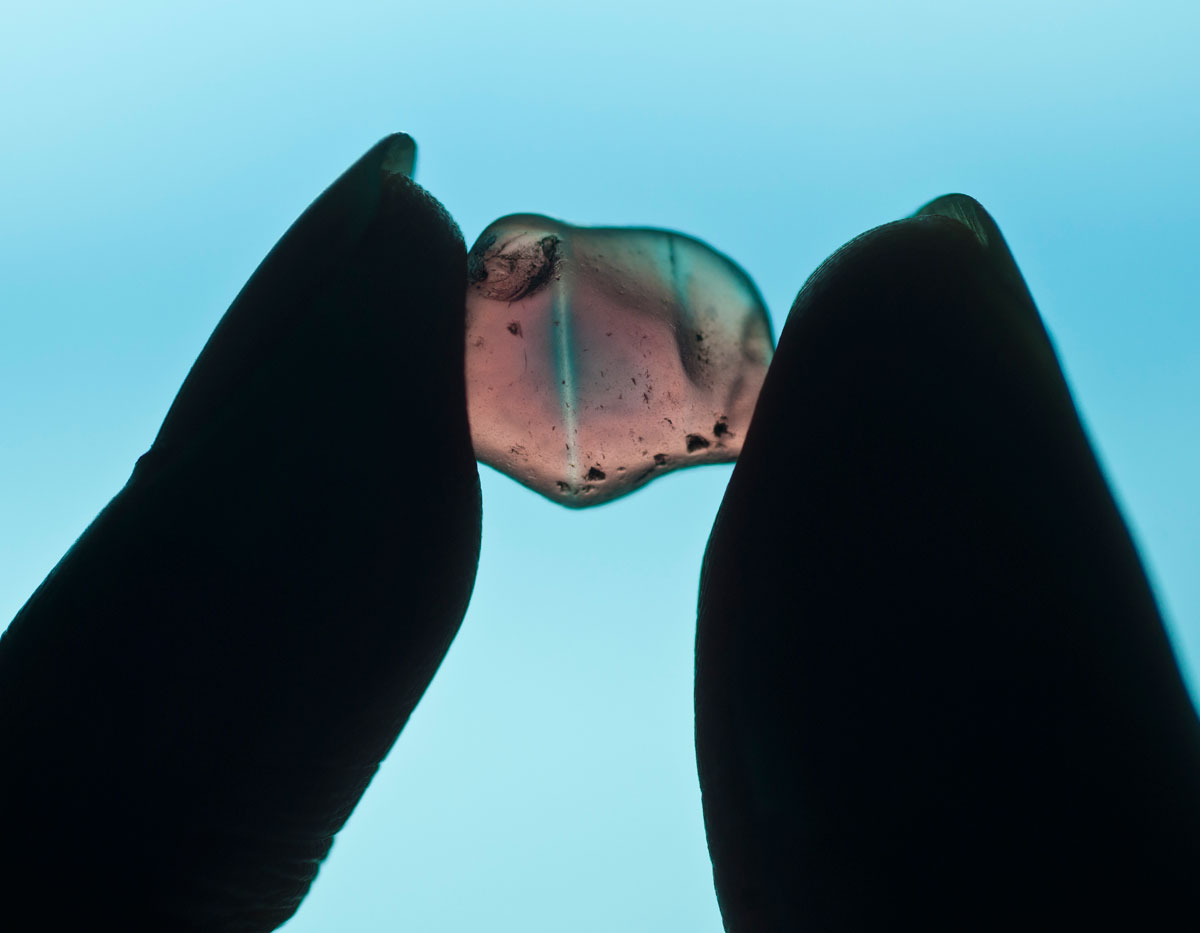

Figure 14. The specimen in the top photo was hand-collected by our party by excavating beneath a bush near Zha Lin in Lower Yu Lin Gu valley, while the lower piece was purchased in a parcel of rough from Tibetan villagers in the mining district. Both clearly show a green core surrounded by a red rim. The top specimen has been polished into a wafer for testing purposes and clearly shows green zoning. Photos: Flavie Isatelle (top) & Richard W. Hughes (bottom)

Figure 14. The specimen in the top photo was hand-collected by our party by excavating beneath a bush near Zha Lin in Lower Yu Lin Gu valley, while the lower piece was purchased in a parcel of rough from Tibetan villagers in the mining district. Both clearly show a green core surrounded by a red rim. The top specimen has been polished into a wafer for testing purposes and clearly shows green zoning. Photos: Flavie Isatelle (top) & Richard W. Hughes (bottom)

Witness the following. According to one internet report:

"Andesine under immersion showing red colour encircling a green core is treated."

"A study on treated red labradorite-andesine feldspars"

by Claudio Milisenda, German Foundation for Gemstones Research, Idar-Oberstein, Germany

Research by the renowned Dr. Claudio Milisenda of the German Foundation for Gemstone Research demonstrated that all andesine with a green core color with a red surrounding outer color is diffusion treated feldspar.

Please note that important issue: ALL feldspar with green core and red surrounding color is treated.

Sadly, no less an authority than Claudio Milisenda himself disputes this statement. When I sent him the two images in Figure 14, he said: "I am aware of this [the fact that a green core with red rim can occur naturally]. Note that I only take this as an indication of a treatment, if there is a complete circular colour zoning with red encircles green and if this zonation is not interrupted by any colourless zones such as the colourless band you see on [your lower photo]. It appears to me that the green is associated with this band and is likely not a primary but a secondary feature."

The same internet report also contained the following statement:

Upon opening of the first stone we found the tell-tale signs of diffusion due to the green color being of zoned formation that was very indicative of diffusion.

Note that both specimens in Figure 14 clearly show green zoning. One specimen was hand collected by us in Tibet, the other purchased by our party from local villagers at the Tibetan mines.

Ancient wisdom

Many years ago, while doing research for my first book, Corundum, I paid a visit to John and Marge Sinkankas' home in San Diego. While browsing through their incredible gemological library (the world's finest; now part of the GIA collection in Carlsbad), John gave me a piece of advice that still rings true so many years later. In his gravelly voice, he said: "Richard, when you are doing research, concentrate on eye-witness accounts. People who have actually been to the mines."

Years later, I had cause to reflect on that during my first visit to Mogok in 1996. Understand, by then I had been to Burma many times, had bought Burmese gems on the Thai border dozens of times and had read nearly every single account of those storied mines in any and every Western tongue. I knew Mogok! And yet I was unprepared for the experience I found. What I thought I knew was only a tiny fraction of what was there to understand. In many respects, one day in Mogok was more valuable than years spent reading the accounts of others. There is no substitute for direct experience.

But even more important is the fact that if you cannot trust your reference specimens, then all your data is next to worthless. Buying specimens on eBay or even sourcing them in the gem markets of Chanthaburi or Teófilo Otoni is not the way to build a reference collection. Reference collections need to be assembled by traveling to the source and, if at all possible, hand collecting specimens. Only in this way can you obtain stones of unimpeachable validity.

This has been the major problem with so much that has been written about andesine. With but a few exceptions, the stones that are being discussed were obtained through third parties. Thus everything written about them rests on a shaky foundation.

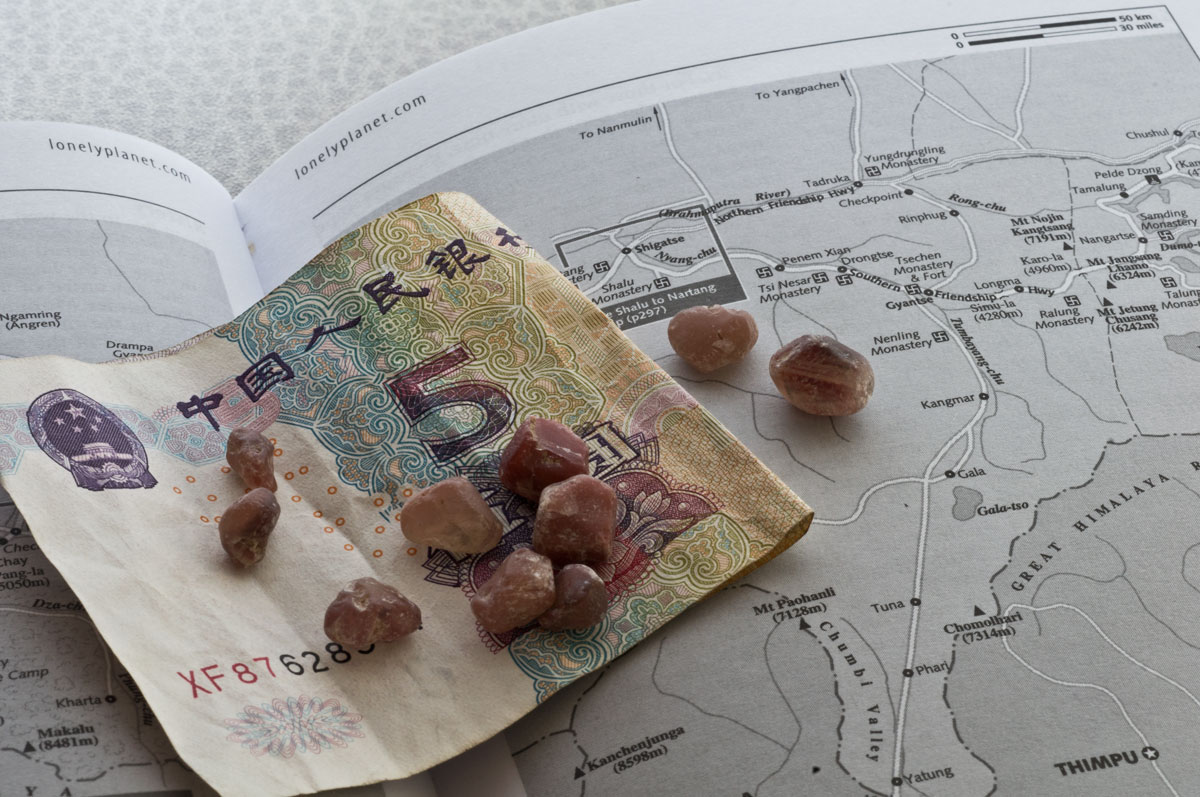

Figure 15. Two parcels of andesine purchased from villagers in Tibet's andesine mining district. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Figure 15. Two parcels of andesine purchased from villagers in Tibet's andesine mining district. Photo: Wimon Manorotkul

Conspiracy factory

There are those who must view from a distance. Some are at an age where travel to places like Tibet is not just an inconvenience, but an actual health risk. For others, the constraint is one of time or money. Each can be excused. But there is no excuse for otherwise healthy individuals who have the opportunity and profess the interest not to visit the mines.

If you are involved in a controversy and are offered a chance to help clear it up with a first-hand investigation, why would you refuse? If you have made major discoveries and others ask to verify your discoveries by examining your samples and verifying your methodology, why would you refuse? Is planet Earth one large conspiracy? Is Barack Obama really Barack Osama?

Barack H. Osama, Gautama H. Obama, Christian, Muslim, priest, commoner, thief, saint, virgin, whore, Obama's in Pakistan, Osama's in the White House.

I love the Internet. But in the end, it's simply a pipe. Yes, it is a huge pipe, but still just a pipe. And pipes carry all kinds of things. It's up to us to decide if we are sucking down sewage or salvation.

BTW, I just heard that China has a secret plan to invade the US. How do I know? I read it on the Internets.

Figure 16. Ahmadjan Abduriyim and a Tibetan gentleman weighing up andesine purchases in Nai Sa village. We were told by the headman of this village that not only had he collected andesine since he was a child, but that his parents and grandparents had done the same. Thus it seems that andesine from Tibet has been collected for several generations. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Figure 16. Ahmadjan Abduriyim and a Tibetan gentleman weighing up andesine purchases in Nai Sa village. We were told by the headman of this village that not only had he collected andesine since he was a child, but that his parents and grandparents had done the same. Thus it seems that andesine from Tibet has been collected for several generations. Photo: Richard W. Hughes

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Li Tong and his wife, Lou Li Ping for opening up their world to us. Wow! Rarely have I travelled to a place and had such great assistance. What can I say? Ms. Mooncake, Christina Iu, was ever cheerful; even in the throes of the AMS doldrums, she always had a smile on her face. And Ahmadjan Abduriyim, the tireless expedition leader, went above and beyond the call of duty. You are the best, man! Anytime you wanna go somewhere wild, make sure you invite me. Also many thanks to my other traveling companions, Brendan Laurs, Flavie Isatelle, Thanong Leelawatanasuk, Young Sze Man and He Qiong. I really enjoyed traveling with each of you. Marco Cheung of Litto Gems also kindly provided us with samples of untreated feldspar from Inner Mongolia, along with diffusion-treated feldspar from the same source.

References & further reading

- Abduriyim, A. (2009) A Mine Trip to Tibet and Inner Mongolia: Gemological Study of Andesine Feldspar. GIA, News from Research. Sept. 10, 27 pp. <http://www.gia.edu/research-resources/news-from-research/andesine-mines-Tibet-Inner-Mongolia.pdf>

- Abduriyim, A. (2009) Andesine mine of Tibet <Movie>.

- <http://www.gaaj-zenhokyo.co.jp/researchroom/kanbetu/2009/2009_08_02_andesine_en.html>

- Abduriyim, A. (2009) Gem News International: Visit to andesine mines in Tibet and Inner Mongolia. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 44, No. 4, Winter, pp. 369–371.

- Abduriyim, A. (2009) The characteristics of red andesine from the Himalaya Highland, Tibet. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 31, No. 5–8, pp. 283–298.

- Abduriyim, A. & Kobayashi, T. (2009) Gem News International: Gemological properties of andesine collected in Tibet and Inner Mongolia. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 44, No. 4, Winter, pp. 371–373.

- Clary, J. & Clary, B. (2008) Sunstone hunting in Tibet. Colored Stone, November.

- Dong, X.Z., Qi L.J. & Zhong Z.Q. (2009) Preliminary study on gemological characteristics and genesis of andesine from Guyang, Inner Mongolia. Journal of Gems and Gemmology, Vol. 11, No 1, pp. 20–24.

- Emmett, J. & Douthit T. (2009) Copper diffusion in plagioclase. GIA, News from Research. 21st Aug.

- <http://www.gia.edu/research-resources/news-from-research/Cu-diffusion-Emmett.pdf>

- Haifu Li (1992) First study of gem-quality Inner Mongolian Labradorite moonstone. Jewellery, Vol. 1, No. 6, pp. 45–47 [in Chinese].

- Japan Germany Gemmological Laboratory (2008) Brief photo report from Tibet about andesine mine. <http://www.sapphire.co.jp/jggl/433.htm>

- Kratochvil, G. (2008) The Great Andesine Scam. <http://www.jewelcutter.com/articles/andesine_scam.htm>

- Krzemnicki, M.S. (2004) Red and green labradorite feldspar from Congo. Journal of Gemmology, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 15–23.

- Laurs, B.M. (2005) Gem News International: Gem plagioclase reportedly from Tibet. Gems & Gemology, Vol. 41, No. 4, pp. 356–357.

- McClure, S.F. (2009) Observations on Identification of Treated Feldspar. GIA, News from Research, Sept. 10.

- <http://www.gia.edu/research-resources/news-from-research/identification-treated-feldspar.pdf>

- Milisenda, C., Furuya M. & Haeger T. (2008) A study of treated labradorite-andesine feldspars. Proceedings of the 2nd International Gem and Jewelry Conference GIT2008, pp. 283–284.

- Roskin, G. (2008) JCK web exclusive: The andesine report. Jewelers' Circular-Keystone, posted November 12.

- <http://www.jckonline.com/article/291011-JCK_Web_Exclusive_The_Andesine_Report.php>

- Rossman, G. (2009) The Red Feldspar Project. California Institute of Technology, 8 pp.

- <http://www.gia.edu/research-resources/news-from-research/chemical-analyses.pdf>

- Thirangoon, K. (2009) Effects of Heating and Copper Diffusion on Feldspar: An Ongoing Research. GIA, News from Research, May 29, 29 pp. <http://www.gia.edu/research-resources/news-from-research/heating-diffusion-feldspar.pdf>

- Yue Cao (2006) Study on the feldspar from Guyang County, Inner Mongolia and their color enhancement, Master's thesis, Geological University of China [in Chinese].

About the author

Richard W. Hughes is one of the world’s foremost experts on ruby and sapphire. The author of several books and over 170 articles, his writings and photographs have appeared in a diverse range of publications, and he has received numerous industry awards. Co-winner of the 2004 Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award from Gems & Gemology magazine, the following year he was awarded a Richard T. Liddicoat Journalism Award from the American Gem Society. In 2010, he received the Antonio C. Bonanno Award for Excellence in Gemology from the Accredited Gemologists Association. The Association Française de Gemmologie (AFG) in 2013 named Richard as one of the fifty most important figures that have shaped the history of gems since antiquity. In 2016, Richard was awarded a visiting professorship at Shanghai's Tongji University. 2017 saw the publication of Richard's Ruby & Sapphire: A Gemologist's Guide, arguably the most complete book ever published on a single gem species and the culmination of nearly four decades of work in gemology.

Notes

This article is the first in Richard Hughes' study of the Tibetan andesine mines. He has written a number of papers on andesine, as follows: